The slow cancellation of the past (Journal of Visual Culture & HaFI, 30)

This is the thirtieth instalment of a collaborative effort by the Journal of Visual Culture and the Harun Farocki Institut, initiated by the COVID-19 crisis. The call sent to JVC’s editorial board, and a wide selection of previous contributors and members of its extended communities, described the task as follows: „There is a lot of spontaneous, ad hoc opinion-making and premature commentary around, as to be expected. However, the ethics and politics of artistic and theoretical practice to be pursued in this situation should oblige us to stay cautious and to intervene with care in the discussion. As one of JVC’s editors, Brooke Belisle, explains: ‚We are not looking for sensationalism, but rather, moments of reflection that: make connections between what’s happening now and the larger intellectual contexts that our readership shares; offer small ways to be reflective and to draw on tools we have and things we know instead of just feeling numb and overwhelmed; help serve as intellectual community for one another while we are isolated; support the work of being thoughtful and trying to find/make meaning…which is always a collective endeavour, even if we are forced to be apart.'“ TH

The slow cancellation of the past

As I write this text, some countries have already entered their second, more severe, peak of the pandemic. The hustle and bustle down the streets indicate, however, that our psyches have plummeted from the heights of emergency, in a 4-6 month drag, into the lows of normalcy and good-old lethargy: One more reminder that there is nothing more out of touch with reality than human consciousness.

Since the surge of sentimental prose, self-indulgent commentary, and naive optimism are finally on the wane, we can recall that neither the pandemic nor the revolution granted a clean slate. While existence was forcing our bodies into a halt, creating the illusion of a tabula rasa, in Lebanon flames rose again on the streets as the currency dived into a freefall. A white police officer in Minneapolis with a history of misconduct pressed his knee on George Floyd’s neck for 9 straight minutes towards death. In Jerusalem’s Old City the Israeli police shot and killed Eyad Rawhi Al-Halaq on his way to his special educational needs school. China effectively rode the chaos to pass national security laws in Hong Kong, crushing any hope for the city’s autonomy. The recession is well underway and abolition is left an unfinished project: People are dismantling monuments to slave trading patriarchs of Euro-Amerikkka, trundling them down to the canals where their ships once used to dock.

In “Statues Also Die” (1953) Chris Marker argues that European culture, product of the removal of Sub-Saharan African masks and sculptures to the European museum, is the carcass of African exuberance: “When men die, they enter into history. When statues die, they turn into art. This botany of death is what we call culture.” Statues of colonialist forefathers at the hearts of Belgian, British, and American empires, in contrast, are alive. More than cities, London, Ghent; Richmond, Virginia are museums of white supremacy where these monuments rightfully belong. Defacing and dislodging them to the river is the first step in exterminating the life captured in these objects. The danger is however in perceiving the empty pedestals left behind as clean slates. There is more to make a true break in the imperialist signifying chain. “An object is dead when the living glance trained upon it has disappeared,” reminds Marker. Because while the artwork disappears, the museum lives long.

The pandemic itself, as one (key) instance in a long pattern of “Disaster Capitalism”[1], is not an opportunity to bank on, nor a new way forward. Its only vocation: not to occupy the future, but to cancel the past.

In hopes of breaking away from what Mark Fisher prophesied as our “slow cancellation of the future”[2]—a tape stuck on repeat, where cultural tropes resurface like a retrospective runway of 20th century—dozen variations on the theme of future have spurned out of the fields of art, design and humanities in the past decade: science-fiction, gulf and cino-futurisms (after afro-futurism), speculative design and speculative fiction. Along with Fisher, artist-designer-thinkers problematized a sense of fatigue with our collective imagination, and so they reinhabited alternative educational programs (micro think-and-do-tanks) in design studios of major global cities. In a way, the correct diagnosis of the shortcomings of 20th century critical discourse in offering constructive toolkits for the future, is responded to with ardent, touch-and-go workshop-format design models that pride themselves in breaking from the standard historical malaise. In the duration of a few weeks to few months, these programs ask their participants to respond with practical proposals to dire issues—be it the pandemic or the environment—that are an accumulation of centuries of capitalization intertwined with racial and colonial injustice. To even begin to correctly identify the problem, however, one requires durational, long-term research. And as much as one can co-opt, and make best of, precarious pedagogy’s modus operandi, knowledge demands its own protracted process. Appeals to sci-fi then become an escape to the future. Is it surprising that, as the economic philosopher Philip Mirowski asserts, the most overused and prosaic conceptual jargons—neoliberalism and the free market per se—are the most understudied and misunderstood objects of research today?[3] Contrary to Fisher’s proposition, in 2020 we may have too much future indeed and not enough the past.

Of course the quest for forging institutional memory is tied to the plight of public education and its aggravating funding crises and over-reliance on the private sector. The emergence of design-studio as the paradigmatic para-educational model is itself a symptom of such pecuniary exigencies in departments of critical thought. At the risk of sounding even more grim, as I’m writing this text, the pandemic has effectively put the faith of several universities in the UK in peril. Goldsmiths, Exeter, Warwick and Sussex in the past few weeks announced massive cuts to their precarious teaching staff—many of them PhD researchers of the same institutions. Goldsmiths has even refused to use the government’s furlough scheme to support its most vulnerable workers. Since 70% of educational labour is handled by these casualised staff, this means doubling the workload of an already overtaxed permanent faculty. This all is taking place against a backdrop of a rapidly gentrified education, disposing of its black and ethnic minority UK students, with astronomical international fees that appeal only to a narrow profit-generating group graced with powerful passports. This week the only black faculty member on a permanent contract at Goldsmiths Art department, Evan Ifekoya, withdrew their labour to take a stand against institutional racial biases pervading the department in a majority white university.

The transient nature of knowledge production today, whether in the solution-averse casualised university or the history-averse design program, is a matter of its exacerbating devaluation. Sustenance of grounded research requires investment, that is, raising the credit-worthiness of discredited forms of knowledge. As walking talking “projects in need of investment”[4], as Michel Feher describes the financialized subject to be, here we can begin to think about our investee positions in academia in more tactical terms: To work on the level of changing the definition of what’s bankable and what’s not. That is, to convince investors—including ourselves as investors in state apparatuses of our countries of residence—of the “attractiveness” of history.

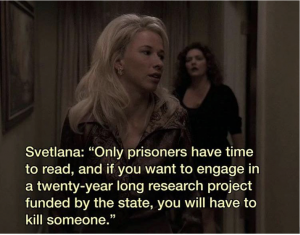

Widespread discussions around prison abolition these days are directly related to this approach. Not only abolition would encourage a reinvestment of capital funds away from the police-prison nexus into development of social structures (housing, health care, education,) but equally essential, abolitionism works on the redistribution of the “unproductive time” of incarceration—turned productive via unsalaried prison labour—into sustaining those life-affirming and time-intensive projects. This supposedly idle time, so far, has been reserved for those called by Achille Mbembe in his Critique of Black Reason (2013)[5] the “Superfluous Humanity”, namely, “those that are unable to be exploited at all”: A condition that is catching up with us in all spheres of automated production. Disqualified even for exploitation and undeserving of wage, the factory streamlines into prison, taking a quick stop at the office. Abolitionist ethics, in essence, imagines the reallocation of this surplus carceral time into the maintenance—and slowing down—of care-based infrastructures.

As schematic as this may sound, it might give us a sense of direction and a cause worth fighting for within our universities while they last.

[1] Naomi Klein, “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism” (2007), New York: Metropolitan Books

[2] Mark Fisher, “Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?” (2009), London: Zero Books

[3] Philip Mirowski, “Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown” (2014), London: Verso.

[4] Michel Feher, “Rated Agency: Investee Politics in a Speculative Age” (2018), New York: Zone Books.

[5] Achille Mbembe, “Critique of Black Reason” (2017) Durham: Duke University Press.

Bahar Noorizadeh is an artist, writer and filmmaker. Her current research examines the intersections of finance, Contemporary Art and emerging technology, building on the notion of “Weird Economies” to precipitate a cross-disciplinary approach to alternative economics and post-financialization imaginaries. She is pursuing this as a PhD candidate in Art at Goldsmiths, University of London where she holds a SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship.

17.06.2020 — Rosa Mercedes / 02