Dream State: hugs, dreams and British psychopolitics (Journal of Visual Culture & HaFI, 18)

This is the eightteenth instalment of a collaborative effort by the Journal of Visual Culture and the Harun Farocki Institut, initiated by the COVID-19 crisis. The call sent to JVC’s editorial board, and a wide selection of previous contributors and members of its extended communities, described the task as follows: „There is a lot of spontaneous, ad hoc opinion-making and premature commentary around, as to be expected. However, the ethics and politics of artistic and theoretical practice to be pursued in this situation should oblige us to stay cautious and to intervene with care in the discussion. As one of JVC’s editors, Brooke Belisle, explains: ‚We are not looking for sensationalism, but rather, moments of reflection that: make connections between what’s happening now and the larger intellectual contexts that our readership shares; offer small ways to be reflective and to draw on tools we have and things we know instead of just feeling numb and overwhelmed; help serve as intellectual community for one another while we are isolated; support the work of being thoughtful and trying to find/make meaning…which is always a collective endeavour, even if we are forced to be apart.'“ TH

Dream State: hugs, dreams and British psychopolitics

In the first dream I had at the start of the UK COVID-19 lockdown, I hugged a stranger. She was wearing some kind of uniform, maybe she was a nurse, or a care-worker, maybe not. I don’t know why I hugged her. I felt an enormous sense of fear, joy and pleasure as we hugged. Did I initiate the hug and she reciprocated? My dream was pervaded by anxiety. Why was I taking such a risk? I was fearful of getting infected, fearful that the police would see us hugging, or someone else would see us hugging and report us to the police. Our hug lasted a few seconds and then it was over.

This week I had two distinct dreams on two separate nights. In the first dream, I was in London and everyone was acting strange, keeping their distance, manoeuvring around each other. A close friend of mine appeared in the dream, distant, not just in terms of her keeping physical distance, but perhaps a more literal expression of ‘social distancing’. She did not smile at me, there was no warmth in her look, she was socially distant. We did not hug.

In the second dream, I was back in London and bumped into a large group of friends who much to my surprise all hugged me, gregariously and with a sense of rebellion. They/we were breaking the rules. Not only that, they had flown out for the weekend to see a special performance, somewhere in Europe, I can’t now remember where. Flights were fine, even going off for a short weekend of fun and art was fine. I felt outside of their fun (they didn’t invite me) and then glad I did not participate in their earth polluting-lockdown-breaking behaviour. I was glad to be hugged though.

During the daily coronavirus briefing on the 27th April 2020, Lynne, the first member of the UK public who was selected to ask a question, asked the Health Secretary Matt Hancock: „I’m missing my grandchildren so much. Please can you let me know if, after the five criteria are met, is being able to hug our closest family one of the first steps out of lockdown?“ Mr Hancock replied: „We understand the impact of not being able to hug your closest family. It affects us all too. We just hope we can get back to that as soon as possible. The best way we can get there, the fastest way, is for people to follow the rules.“

“Every state needs to know about the people it rules” writes Erik Linstrum, author of Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (2016), charting an unusual project of the British empire: to collect dreams from the people of South Asia, Africa and the Pacific. Linstrum explains how particularly after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, British officials across the empire shared two related preoccupations: the fear of further uprisings, and the conviction that the inner lives of their subjects – their beliefs, their attitudes, their emotions – were exceedingly difficult to determine. Linstrum’s fascinating book focuses on the work of an anthropologist at the London School of Economics (LSE) named Charles Gabriel Seligman. Seligman was a longtime adviser to colonial governments, which funded his research and helped to train colonial officials at the LSE. He was also influenced by the work of Freud and Jung. In the 1920s, on Seligman’s instruction, hundreds of dreams were collected from across the British empire – from the Indian subcontinent, Nigeria, Uganda, Australia, the Solomon Islands and elsewhere. However, the results were not what they expected. “The common thread running through all the accounts”, Linstrum writes, “was a twist on the Oedipal story. The oppressive patriarch, a largely fantasied figure in the European context, was here embodied in the very real force of the ‘white man’ and the colonial state behind him”. It turns out, concludes Linstrum, that Seligman had chronicled the psychic wounds of colonialism, revealing a political order fundamentally at odds with Britain’s self-understanding.

Colonial anthropologists would have been, no doubt, quite keen on Facebook’s current project of building a new kind of “non-invasive brain-machine interface” that silently turns thoughts to text, or armbands that can hear words with your skin. They would certainly be jealous of Google’s mass collection of behavioural data, modelled into techniques of governance described by Shoshana Zuboff as “surveillance capitalism” (2019). Perhaps, this is why Demis Hassabis, a co–founder of Google’s artificial intelligence division, DeepMind, attended a meeting of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) on 18th March 2020, when the group was considering whether the UK should go into lockdown. DeepMind had previously processed millions of healthcare records from an NHS hospital trust as part of a scheme to design a diagnostic app, in an arrangement subsequently found to have contravened data protection law.

After keeping the names of SAGE advisors secret for more than a month since the lockdown, the UK government finally published them on the 7th May 2020. Well, all those who gave their permission. Conspicuously missing from the document were Dominic Cummings, current chief advisor to Boris Johnson, and Ben Warner, the data scientist who ran the most recent Conservative party’s general election campaign model and worked with Cummings on Vote Leave campaign. According to The Guardian both Cummings and Warner attended the SAGE meeting on the 23rd March 2020.

Less than two years ago, Dominic Cummings was found in contempt of Parliament for refusing to appear in front of the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee (DCMS) which was investigating “Disinformation and ‘fake news’”. Cummings might hate committees but he loves AI, predictive data-modelling and psychographic scores – which is probably why he hired a digital advertising and software development company Aggregate IQ (AIQ) for the Vote Leave campaign (on their links to Cambridge Analytica see this article by Carole Cadwalladr). Unlike Cummings, the owner of AIQ, Jeff Silvester, testified in front of the DCMS Committee. He explained how their first work for SCL Group/Cambridge Analytica was to create a political customer relationship management software tool for the Trinidad and Tobago election campaign (see page 48). The DCMS Committee’s final report, published a year ago, concluded that “AIQ carried out online advertising work for Brexit-supporting organisations Vote Leave, Veterans for Britain, Be Leave and DUP Vote to Leave. The majority of the adverts were created by AIQ on behalf of Vote Leave.”

Let’s just pause over Jeff’s words for a moment: political customer relationship management software tool.

What does this even mean?

The SCL Group, was a British private contractor working for the UK Ministry of Defence, US Department of Defence and various NATO militaries, for whom they carried out behavioural change programmes (basically, psychological warfare). A comparison of the map of SCL Group’s operations with a map of the British Empire reveals astounding similarities. SCL Group spawned several other entities, e.g. SCL Elections, focused on influencing elections, out of which Cambridge Analytica emerged in 2012, with backing from the US hedge fund billionaire and Donald Trump donor, Robert Mercer, who became the majority shareholder. The primary aim of Cambridge Analytica was to adapt and deploy tactics SCL had used on military projects for election politics in the United States and the UK.

The transference of military-grade persuasion tactics onto its own population, echoes deeply with words of the poet Aimé Césaire, who in his well-known essay Discourse on Colonialism argued that what in Europe is called ‘fascism’ is just colonial violence finding its way back home. Kader Attia and Ana Teixeira Pinto explain how Césaire’s warnings went unheeded, and how instead, The Authoritarian Personality by Theodor Adorno et al., published the same year as Discourse on Colonialism (1950) was more widely read. In the opening text to the conference: “The White West III: Automating Apartheid” , that took place in Vienna earlier this year, Attia and Pinto describe how The Authoritarian Personality developed the F scale (F for fascist) in order to:

“gauge the psychological predisposition for fascism among the democratic citizenry, leaving the post-war consensus to settle on the notion that fascism was a personality trait, resulting from the devolution of the individuated liberal subject. Still dominant today, this tendency to psychologize fascism fails to incorporate the colonial dimension, obscuring the continuities between fascism and the biopolitics of empire, and ultimately depoliticizes both” (Attia and Pinto, 2020).

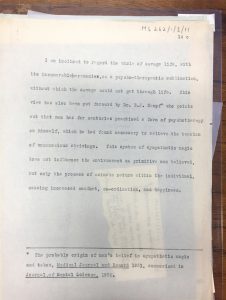

Last year, I visited the Charles Gabriel Seligman archive collection together with artist and collaborator Susan Kelly. We were researching the rise of private contractors operating in the nexus of corporate and state military apparatus, as well as academia, who perfect models of psychological profiling and tactics of behavioural control. We traced resonances of this phenomenon to the histories of dual psychological and military practice in counter-insurgency struggles in the former British colonies where ‘rehabilitation’ techniques were used to ‘cleanse’ and re-constitute compliant colonial subjects. Following in the trail of Linstrum’s book, we found ourselves inside The Royal Anthropological Institute in central London, looking through the dusty boxes. Under the entry number MS262/1/3/11, Seligman writes: “I am inclined to regard the whole of savage life, with its innumerable ceremonies, as a psycho-therapeutic sublimation, without which the savage could not get through life.”

“Suggestions as to Method of Recording Dreams of Non-European Races” is another entry written by Seligman, addressed to ‘the investigators’ in which he gives a number of instructions, ending with:

“It may help the investigator to remember that although Freud, to whom we owe the first clear statement of dream mechanisms, believed that dreams refer predominantly to the sexual sphere, further research, particularly experience of the war neuroses shows that any emotion especially if accompanied by psychic conflict, as in the struggle between fear and duty, may be the efficient cause of dreams. Jung, if I understand him aright, regards the dream as an attempt (usually by way of analogy) at adaption to present or future demands or difficulties while it has been suggested that one function of the dream is to make some of life’s problems clearer to the dreamer “ (Charles Seligman, archive entry MS262/5/6/4).

Around the same time of our visit to Seligman’s archive, Dominic Cummings published a long blog-post titled: “On the referendum #33: High performance government, ‘cognitive technologies’, Michael Nielsen, Bret Victor, & ‘Seeing Rooms’” . Predictably (and, one doesn’t need a data-modelling tool to know this) it doesn’t feature a single reference to an idea by a woman (which is kind of a relief). In the text, Cummings techno-evangelises about cognitive toolkits, AI and then, referring to the Amazon owner’s desire to colonise the space, writes: “Jeff Bezos is explicitly trying to revive the Mueller vision and Britain should be helping him do it much faster.”

Less than a month later, in July 2019, Cummings was appointed as the chief advisor to the British Prime Minister.

Recent disclosure from NHS England to Byline Times, reveals that a number of highly controversial contracts containing confidential data from tens of thousands of COVID-19 hospital patients have been awarded to technology companies: Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Palantir and Faculty. The system is now live and being used to inform senior health officials on the latest situation at the daily Downing Street briefings. Similar handover of public ‘telehealth’ to the big tech companies is happening in the US, where Naomi Klein writes “something resembling a coherent Pandemic Shock Doctrine is beginning to emerge. Call it the ‘Screen New Deal’.”

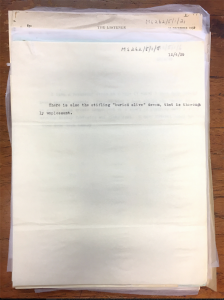

As well as collecting dreams from the people of South Asia, Africa and the Pacific, Charles Seligman collected dreams from the British public. In the folder marked ‘further dreams, articles, psychical research, art, various’ I came across two letters from Maude Meagher, dated 12th April 1929. The first one asked: “Do you know the ‘aloneness’ dream? It was a recurrent dream of my childhood, and several people have given me various versions of it.” The second one simply said: “There is also the stifling, ‘buried alive’ dream that is thoroughly unpleasant”.

All images © Royal Anthropological Institute, “Seligman, Charles Gabriel Collection“, photography: Margareta Kern and Susan Kelly, 2019