Operational Images and Images of Operations. The Use of Drones and “Action Cameras” on the Ukrainian-Russian Front

At the start of Harun Farocki’s film WAR AT A DISTANCE (2003), black-and-white electronic images with fire control information reveal a number of tubular buildings linked by straight roads, forming a highly geometric pattern. The viewer soon identifies a military airport. Suddenly, one of the buildings explodes, then another. Finally, a bridge collapses in a spray of explosions, while the analytical voice that runs through the film states factually:

1991. Images like these were seen from the Gulf War. Aerial images. In the centre, the crosshairs. There were also images from the tip of the projectile, from cameras that plunged towards their target.[1]

In the early 2000s, the German filmmaker devoted a film-research to so-called ‘operational images’ produced by remote-controlled missile warheads, combat drones and firing simulators. Alongside other images from surveillance, industrial production or simulation operations, Harun Farocki defines these images as operational because they ‘do not represent an object’, but ‘are part of an operation’[2]. In one of the many analytical loops that structure Erkennen und verfolgen, the filmmaker revisits the same explosion scenes and explains:

Such operational images must surely open up a different view of the world they depict. They belong to a different genre than images intended to entertain, educate or sell, and should be as different from these as a workhorse is from a riding horse[3].

Following on from the work of Harun Farocki, Volker Pantenburg proposes to classify operational images according to three types of ‘operationality’[4] – a tripartition that we will adopt in this work: A) Purely functional operationality. These images, whose existence is purely digital, can only be considered as part of a technical process. They are most often algorithmic. Their visualisation is therefore considered subsidiary. B) Instrumental operationality. These images are created to ‘establish or facilitate a military or non-military operation’[5]. C) Broader operationality. This includes ‘any type of image that actively initiates processes and actions, whether technical or non-technical, produced by humans or non-humans’[6]. The notion of operationality thus merges with that of performativity.

Since February 2022, the war in Ukraine provoked by the Russian invasion has led to an unprecedented production of operational images from the military conflict, filmed mainly by drone cameras present on the battlefield. Gradually, Ukrainian and Russian combat units began to broadcast a fraction of these hundreds of thousands of operational images of the fighting on social networks, which were then remediated on various broadcast channels: Telegram-type messengers, social networks (X-Twitter, Facebook or ВКонтакте), streaming networks (YouTube or Rutube). These images were then repeated on international Cable and Web TV[7] or on forums and livestream sites frequented by hundreds of thousands of international ‘warporn’ enthusiasts’[8].This article sets out to analyse this recent and dizzying production of operational images in the light of the notion of operational image defined by Harun Farocki and the typological classification in terms of ‘operationality’ proposed by Volker Pantenburg.

On the front line of the war in Ukraine, a first type of operational image of a typically instrumental nature comes from civilian drones equipped with video recorders on memory cards which, from the start of the war, were either transformed into tactical surveillance tools for the conduct of battles on the ground and linked to command posts, or used as flying platforms for dropping grenades or mini-bombs on small fixed targets. Purchased on international markets, sometimes by crowdfunding[9], these cheap leisure drones (of the DJI Mavic type for example) are ‘consumed en masse’ on the front line, many being lost either because of electronic countermeasures put in place by the adversary, or destroyed by small arms, or even shot down by collisions with enemy drones in ‘aerial battles’ broadcast on social networks[10].

A second category of operational images, also of the instrumental type, is produced by the many examples of loitering munitions used since the start of the Russian invasion. These kamikaze drones, such as the Russian-made Lancet or the Switchblade manufactured in the USA, have ranges of 30-50 km and are equipped with cameras that enable them to be guided remotely[11]. Encrypted images are transmitted to operators up to a few milliseconds before impact, and – when recorded by the operators – result in ipso facto operational images. One of the singularities of the war in Ukraine is the massive use of FPV (First Person View) game drones transformed into loitering munitions. Piloted using goggles, these cheap quadcopter-type drones can track fast-moving targets from a distance and detonate them on impact[12]. Trained pilots, sometimes operating in ‘swarms’, are able to destroy tanks, vehicles and motorbikes, or even hit soldiers on the march. Since 2023, the Russian and Ukrainian armies have been making increasing use of locally manufactured military drones, which are more powerful and resistant to electromagnetic jamming, sometimes linked by fibre optics to the flight control systems[13].

A third type of instrumental operational imagery is provided by military reconnaissance or attack drones (of the Bayraktar TB2[14] type used mainly at the start of the war, or of the Orlan-30 type, etc.). These images are not widely disseminated, as their specific characteristics and resolution, which are constantly evolving, must remain secret for strategic reasons.

Finally, a fourth type of image of the frontline is produced by small action cams attached either to helmets or to the rifles of infantry units on the ground, particularly trench assault units, or to the turrets of combat vehicles (tanks or troop transport vehicles) or even inside medical vehicles. However, these images filmed ‘in military operations’ are not strictly speaking ‘operational’, as they are not essential to the conduct of the operation.

So the notion of operational images needs to be complexified. The installation of action cams on helmets or combat vehicles or the recording of an attack by a grenade-launching surveillance drone may be motivated by reasons that have nothing to do with the actual conduct of the military operation, the identification of targets, the piloting of the drone or the verification of the achievement of the objectives set by the operation: some of these images sometimes exist essentially for propaganda purposes in the media sphere that extends the battlefield (Image Warfare[15]), for the urgent need to recruit new combatants, or to finance the war effort (notably through private donations).

We therefore propose the following definitions, applicable to the military field:

- Operational images: images produced during an operation, the existence of which is essential to the conduct and execution of the operation. The recording of these images may be part of the mission itself. Operational images can be categorised into three types: purely functional, instrumental and extended (Volker Pantenburg[16]).

- Image of operation: refers to an image produced/captured during a military operation, but whose very existence is not essential to the execution or conduct of the operation as such.

Images taken from a drone during an assault on a trench and broadcast on a command post screen will be considered operational images, since they are essential to the conduct of the operation (in the primary and figurative sense of the term), even if they are later remediated in various media. On the other hand, images produced by a series of action cams attached to the helmets of members of an assault group attacking the same trench will be considered as images of operation, even if from a strictly military point of view they allow an analysis of the battles conducted, an assessment of the victims of the offensive by the military hierarchy, or a gauge of the occupation of the ground by the forces involved. However, the direct conduct and completion of the operation are not dependent on the existence of these images, which are therefore subsidiary to them.

These operational images, which are typical of the ‘invisual’[17] space, as well as the images of operations from the war in Ukraine, travel and live in a process of constant ‘remediation’[18]. Their dissemination over multiple channels leads to a veritable ‘remediation battle’[19], which extends the battlefield beyond the front lines[20]. These operational images and images of operations are subject to transformation processes (editing, sound, graphics, colour grading, etc.), which we propose to analyse here. We therefore hypothesise that the remediation of operational images and images of operations is accompanied by transformation processes that are subject to a dual dynamic. On the one hand, they aim to fit these operational images – which often lack aesthetic or ‘cinematographic’ qualities – into the existing fabric of war images, influenced in particular by the fictional films and video games produced by the ‘Military Entertainment Complex’[21]. The culture of ‘militainment’[22] that has grown out of this has produced quasi-prescriptive aesthetic standards. Secondly, the processes of editing and aestheticising these images help to integrate them into the propaganda, recruitment and fundraising operations that accompany military operations and the conduct of war, both nationally and internationally. The complexity of the processes of poly-remediation at work will therefore not be considered here, nor the analysis of the dynamics of battlefield extensions induced by these remediations that link military operations to spaces beyond the battlefield.

From the first months of the Ukrainian War, battalions such as ЗСУ Підрозділ TERRA, 3-тя окрема штурмова бригада (3rd Assault Brigade), К-2 54 ОМБр (Battle Group K-2, Brigade 54), 47-ма окрема механізована бригада (47th Separate Mechanized Brigade ‘Magura’) or the AZOV battalion to name but a few began broadcasting short and medium-length films of the battles fought, sometimes even in the form of ‘mini-series’ of 3 to 5 episodes. Here, we will analyse two mini-series with long sequences, using film analysis practices that are generally applied to cinema films: what editing aesthetics (image and sound) are used to interweave the different types of images from the battlefield, leading to hybrid structures that combine operational images and images of operations ? What are the different filmic aesthetics and cultural and political reference systems that may have fuelled these short films from the trenches, within alternate montages that respect the editing principles typical of action films and borrow aesthetic codes often found in FPS (First-person shooter) video games[23] ?

On 20 October 2023, Urkainian film-maker Oleg Sentsov, who had become commander of an assault unit in the 47th ‘Madura’ Brigade, posted on his Facebook page a written description of a battle fought for nearly 5 hours on the edge of fields near Avdiivka (Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine), along with an image of the battle[24]. Tasked with defending a trench position, his unit, with several wounded, had to retreat in the face of a Russian attack led by a column of tanks. The members of the unit owed their survival to two armoured vehicles that had come to evacuate them under enemy fire. Wounded by shrapnel, Oleg Sentsov posted a 33-minute film on Facebook a month later with the following message: ‘Facebook usually hides such videos, so I ask you to repost them so that more people can see the truth about the war[25]’. Shot with action cams attached to helmets, this montage of raw footage, without music or artifice, documents assault and defence actions in a trench that fills up during combat with wounded soldiers being cared for by a soldier-nurse (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Footage broadcast by Oleg Sentsov on his Facebook account @oleg.sentsov on 22 November 2023.

On December 6, 2023 after excerpts of this sequence were remediated in particular on CNN or TVP Poland, a new 27-minute film entitled ‘ВАЖКИЙ БІЙ: 47 бригада тримає оборону Авдіївки, противника в рази більше. HARD FIGHT: 47th Brigade holds defence of Avdiivka, enemy outnumbered many times over’ is broadcast by the official Ukrainian army website Збройні сили України // Army TV – Ukrainian military channel[26].The original Oleg Sentsov film has been re-edited, adding operational footage from the surveillance drones that filmed the battle, footage taken from the PFV suicide drones pouncing on Russian tanks and soldiers, footage taken from the combat vehicles that come under enemy fire to exfiltrate the group of soldiers, as well as interviews with a drone pilot from the brigade as well as the drivers of the two armoured vehicles. Electronic music is added to dramatise some of the action, and the end credits list the various filming and post-production technicians involved in the making of this new film.

Alternate editing is carried out between combat sequences filmed in the trench and the same sequences filmed from the drones. Action sequences are built around grenade throwing, machine gun bursts, soldiers’ movements and tank movements. The offensive sequences using grenades are systematically built around the same structure: the preparation and throwing of the grenade are filmed from the trench by the infantrymen’s cameras (images of operations). The explosion of the grenade in the enemy trench is recorded from a drone (instrumental operational images), but with sound recorded from the launch trench. Finally, the montage takes us back to the trench, from where we can see the column of smoke rising above the explosion zone (images of operations).

Figure 2 – Alternate montage of grenade throwing. Extract from the film« HARD FIGHT: 47th Brigade holds defence of Avdiivka, enemy outnumbered many times over” (Збройні сили України // Army TV – Ukrainian military channel, YouTube, 6 décembre 2023)

When Kamikaze drones are sent out in swarms to try to ‘’disengage‘’ the Ukrainian unit which, with many wounded, is no longer operational for combat, we see alternate editing of shots filmed by a surveillance drone and those filmed by the FPV kamikaze drone until the video signal signalling the impact and explosion of the drone and its payload is interrupted, followed by a return to images from the surveillance drone attesting to the explosion (Figure 2-3). These sequences consist solely of instrumental operational images. The words of infantry soldiers announcing the passage of the FPV drone are often edited in voice-over (sounds of operations).

Figure 3 – FPV drone attack on a Russian armoured vehicle. Extract from the film “HARD FIGHT: 47th Brigade holds defence of Avdiivka, enemy outnumbered many times over” (Збройні сили України // Army TV – Ukrainian military channel, YouTube, 6 December 2023).

The montage then focuses on one of the pivotal moments of the battle: the exfiltration of the unit under enemy fire (Figure 4). One of the tanks that has come to pick up the wounded is hit by a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG), the impact of which is filmed by a camera mounted on the turret of the armoured vehicle itself (Images of operation), before the montage takes the viewer back over the trench that is about to be captured by the Russian soldiers (instrumental operational images).

Figure 4 – – Impact of a Russian RPG projectile on a Ukrainian armoured vehicle. Extract from the film ‘HARD « HARD FIGHT: 47th Brigade holds defence of Avdiivka, enemy outnumbered many times over” (Збройні сили України // Army TV – Ukrainian military channel, YouTube, 6 décembre 2023).

While Oleg Sentsov’s original film is a long (35 min), unadorned window into a brutal moment of war captured from a trench by three combatants, the film edited by the Ukrainian army’s audiovisual services clearly has a multiple purpose: on the one hand, the film celebrates the bravery and courage of the ‘fearless’ Ukrainian fighters, particularly through the sometimes darkly humorous analyses made afterwards by the fighters interviewed, who never fail to mock the outnumbered but incompetent Russian forces. Their accounts are technical, consisting of strategic and technological reports designed to demonstrate their mastery of military science and the coordination of the operation. The presence of instrumental operational images reinforces the impression of strategic mastery of the battlefield, which adds to the composure shown by the unit commander, particularly when the column of Russian tanks arrives. On the other hand, it is also clear that the film’s makers wanted to highlight the key role played in the outcome of the battle by the equipment supplied by the European and American allies: the Leopard tanks donated by the Europeans decimated the Russian column and the Bradleys combat vehicles built in the USA were used to extract Ukrainian fighters in bad positions. The film, which has been viewed 985 000 times as of 20 September 2025, also details the efficiency of the transport and care chain that enabled the wounded to be brought to the medical stabilisation point in a short space of time. Even though the operation was a failure for the Ukrainian army, the montage, which interweaves operational footage and footage of the operation, celebrates Ukrainian resistance in the face of an adversary with more troops, thus contributing to the ongoing informational war effort that extends the battlefield onto the media stage. However, this short film reminds us that a unit other than the one led by Oleg Sentsov, present in an adjacent trench, was totally decimated during the attack, this time in an anonymous fashion with no images.

Produced by the 3-тя окрема штурмова бригада (3rd Assault Brigade[27]) in 2023-2024, the trilogy of medium-length films entitled ‘The Assault. A trilogy’ also interweaves operational footage and operational footage from several battles fought by this Ukrainian army special forces assault brigade in the Bakhmut region[28]. This brigade is known for publishing hundreds of videos on its official websites (YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and TikTok). In the detailed descriptions that accompany them, links are systematically provided to volunteer recruitment sites, both national and international. Commanded by Andriy Biletskyi, a self-proclaimed far-right politician, founder of the Patriot of Ukraine activist group and former commander of the AZOV battalion formed in Maruipol in 2014, the 3rdAssault Brigade is made up exclusively of national and international volunteers, including former members of the AZOV special forces. Although it is now part of the Ukrainian Army’s special forces[29], it still has an openly proclaimed ultranationalist streak, as the brigade’s website makes clear: ‘The foundation worldview principles of the Azovian units are Ukrainian-centrism, traditionalism, hierarchy and responsibility[30]’. The videos posted by this assault brigade, which specialises in trench attacks, each have millions of views on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/@ab3army) and Telegram (#@ab3army). They are known as much for the ferocity of the unfiltered combat that they present as for their technical and aesthetic ‘qualities’, probably using technicians trained in editing and colour grading. Fragments of videos from the brigade, easily identifiable since its logo is systematically embedded in the centre of the image, circulate around the world, without the identity or political opinions of the volunteers making up the brigade being mentioned and thus known to viewers.

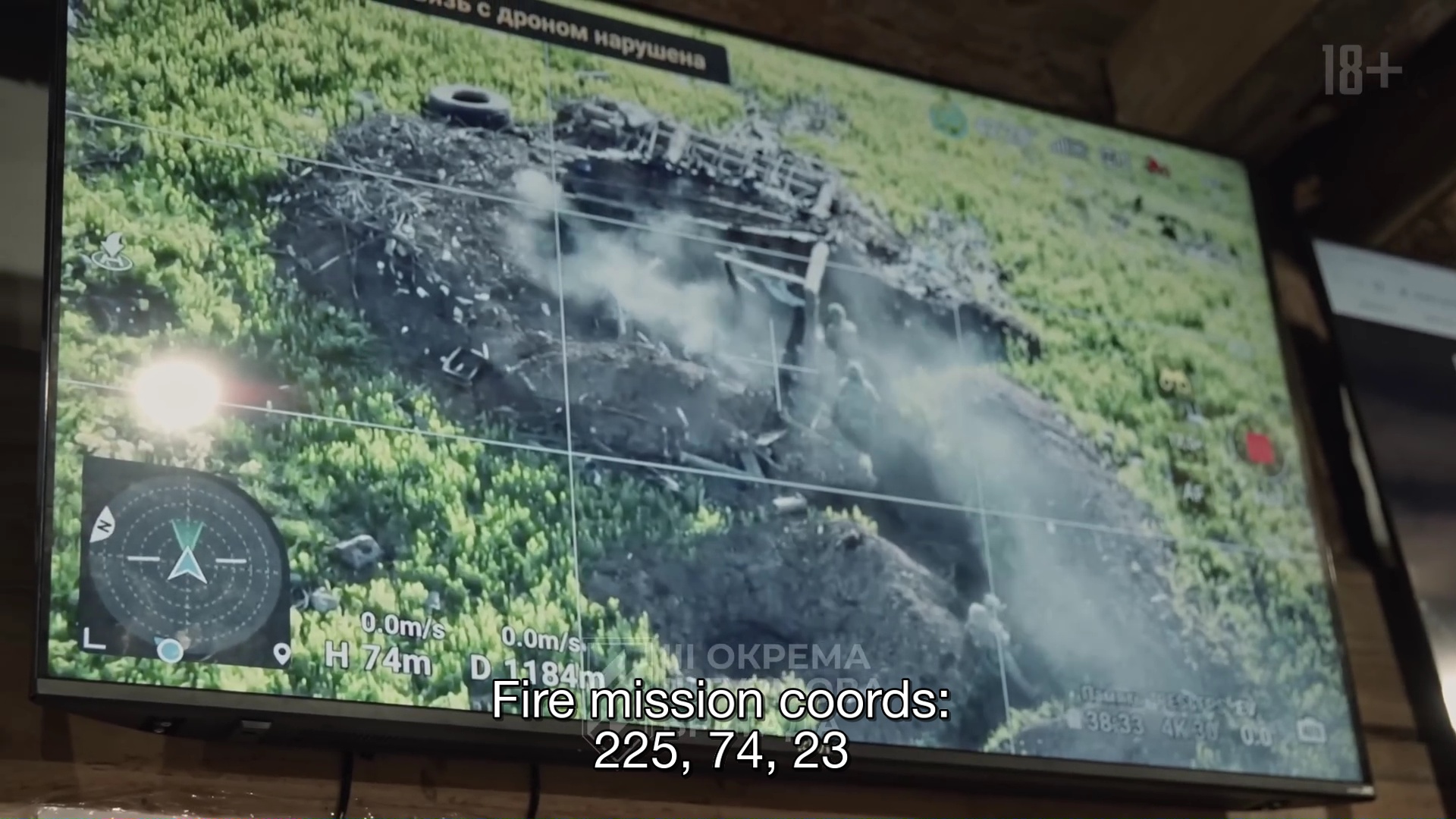

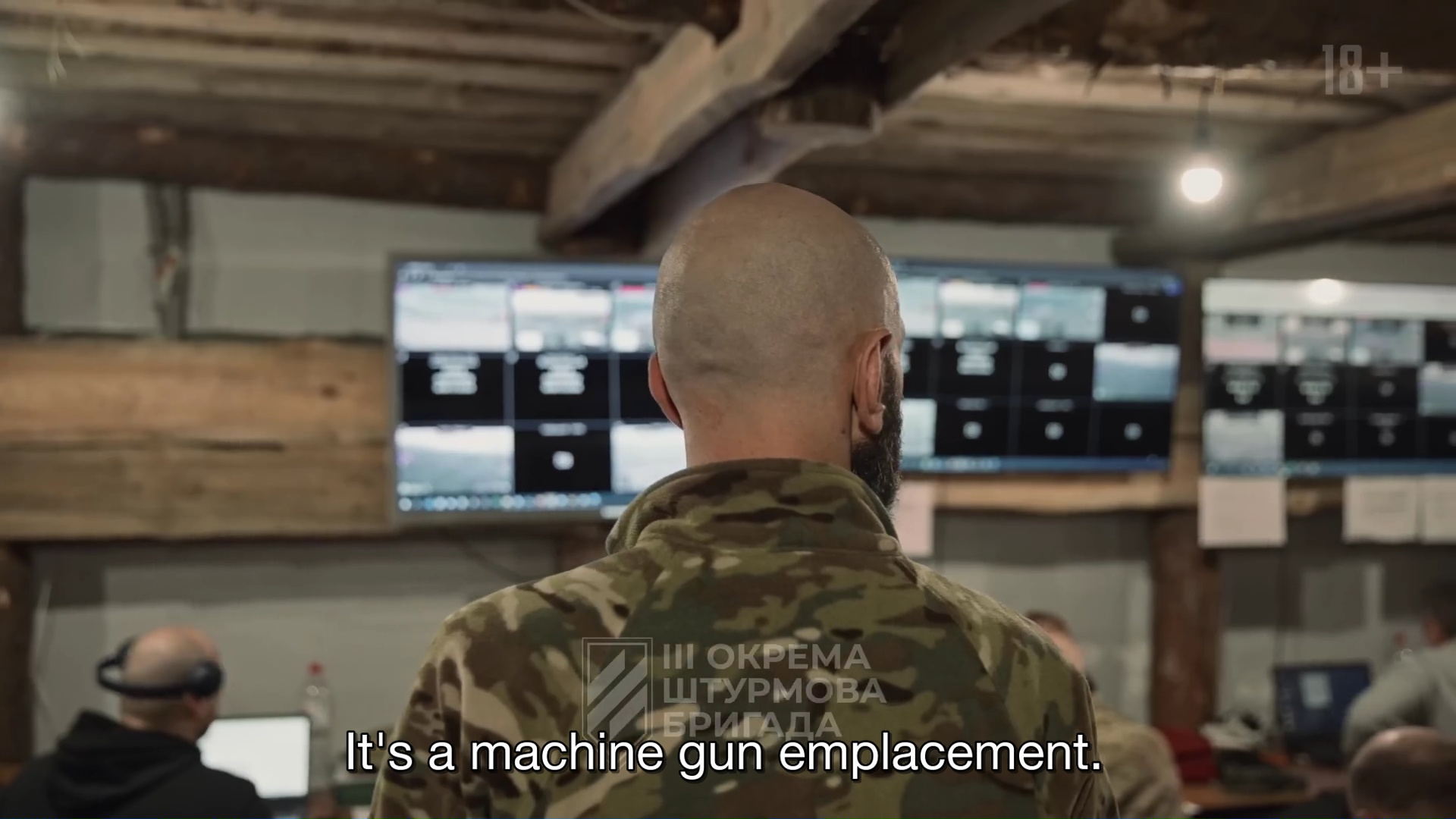

The first episode of the mini-series, entitled Bridghead, interweaves image of operations filmed by action camsattached to the helmets of soldiers storming the trenches and underground shelters[31] of the ‘Warthog’ and ‘Houston’ positions on the outskirts of Bakhmut in July 2023 with footage filmed in the brigade’s command posts. The operational images of the battle filmed by the surveillance drones are shown on large screens in the command posts and viewed by the unit commanders (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Attack on the ‘Warthog’ position (Extract from ‘The Assault. A trilogy’, 3rd Assault Brigade. YouTube, 24 July 2023).

Alongside the images from the grenade-launching drones, the images filmed by the surveillance drones are the only operational images in the strict sense of the term in this sequence, as they are essential to the conduct of the operation. The non-operational cameras filming the theatre of operations are present inside the command post, on the ground (fixed to the helmets of the combatants), and in and on the turret of the tank that has come to destroy the ‘Warthog’ position with cannon fire. Low-volume electronic music with haunting rhythms is added to the montage, creating a continuous ‘pulse’. A series of slow-motion shots show grenades flying through the cloudy sky, only to fall back into the enemy fortifications.

Figure 6 – Throwing a thermobaric grenade – slow motion. Note the 18+ symbol added to the image, as required by streaming channels such as Youtube, and the 3rd Assault Brigade logo, centred at the bottom of the image (Extract from ‘The Assault. A trilogy’, 24 July 2023).

These images have clearly been graded by increasing colour saturation and contrast, reinforcing the image’s plasticity, density and ‘luminosity’ (Figure 6). The use of slow motion, accompanied by music with lyrical overtones, to emphasise these successive throws leads to a serial iconisation of these military acts. This recurrent use of slow motion borrows from the aesthetics of action films, which do not hesitate, through the artificial temporal extension of shots, to emphasise the impacts (of bullets, blows), to dwell on singular plasticities, to ‘celebrate’ characteristic gestures that are gradually erected as symbols of combat[32]. Unlike Oleg Sentsov’s film, which places these acts within the ongoing dynamic of the battle, the mini-series The Assault produced by the 3rd Assault Brigade turns these slow-motion grenade throws into allegories of ‘close combat’ with an uncertain outcome. The recurrent use of footage from operational surveillance cameras broadcast from command posts is also reminiscent of their use in Ridley Scott’s film Black Hawk Down (2001), set as a benchmark for action films by many Ukrainian fighters and drone pilots[33]. The use of action cams also makes these sequences part of the aesthetic of First Person Shooter (FPS) video games[34]. This aesthetic porosity between FPS video games and images of operations filmed by action cams placed on the helmets of the belligerents is even affirmed in the expressions used to describe these images on networks such as YouTube, since we now speak of war sequences filmed in FPV (First Person Video). In this way, these hybrid sequences – since they include both operational images from drones and images of operations in the trenches – move these operational war images into the territory of the genre film, outside the classic sphere of the combat documentary film, as initiated in particular during the Vietnam War[35].

The three episodes that make up the mini-series The Assault begin with short, fast-moving montage sequences that act like audiovisual teasers, leading up to credits that display the episode titles in ‘letters of fire’. These aesthetic constructions are akin to video clips: the beat of the music acts like a pulse giving rhythm to the montage, which condenses the most spectacular moments of the action into ellipses. Filmed in the summer of 2023 along the Siverkskyi Donets-Donbass canal, The Way Forward, the second episode of the mini-series, begins with a montage of slow-motion footage of assaults as soldiers recite in chorus and voice-over a chant from their brigade: ‘Let me know no fear. Let me know no hesitation. Strengthen my spirit. Harden my will. Holy… Powerful… And free. Glory to Ukraine! Glory to the Heroes’. This is followed by a montage of short, brutal actions punctuated by the sound of gunfire and bombing, backed by the pounding, continuous beat of electronic music. In contrast to the crude combat sequence edited by Oleg Sentsov (47th Brigade), this second episode, The way forward, inscribes the assault both in the pure military tradition (the brigade’s song ‘before the battle’ and the detailed explanation of enemy losses in a written announcement) and in what might be described as a war-turned-show. Midway through the film, the montage devotes a few minutes to a hand-to-hand battle between the lead assault group and some entrenched Russian soldiers (Figure 7). The surveillance drone then delivers operational footage of this assault in which the combatants are intertwined in the network of trenches.

Figure 7 – Attack on a Russian trench by the leading group. Siverkskyi Donets-Donbass Canal region (Extract from ‘The way forward’, 3rd Assault Brigade, Youtube, 14 October 2023)

Suddenly, a shell falls on the assault group. The editing then makes a link between the explosion filmed from a drone (operational images) and the GoProTM type camera mounted on the helmet of the lead soldier (images of operation) who collapses amid the crash and the clods of earth, before returning to the surveillance shot showing a tree collapsing near the group. This moment of uncertainty – did the soldier carrying the camera, whose nom de guerre is ‘Afghanistan’, survive the bombing? – is underlined by a change in the tonality of the music at the very moment of the explosion, which is broadcast in slow motion (Figure 8). The monotone of the music acts to suspend the action. Gradually, the soldier starts to move again and we hear his complaints before he announces that he is wounded.

Figure 8 – Explosion of a mortar shell and wounding of soldier ‘Afghanistan’. (Extract from « The way forward », 3rd Assault Brigade, summer 2023)

Such sequences, which alternate between different cameras filming the battlefield, are inspired by the editing practices typical of ‘fictional’ war films produced by the film industry: the most spectacular actions of the battle are dramatised by the densification of the changes in shot values, which aim to underline the violence of the confrontations[36].

The continuous presence of cameras at the height of the fighting in Ukraine, particularly during sequences showing wounded or dying soldiers, and the public broadcasting of these images, inaugurate unprecedented practices that extend the battlefield. Certain military operations, carefully selected by one of the belligerent camps and usually hidden, become public objects. While images of corpses and deaths are blurred in the versions uploaded to YouTube, they are shown ‘in full representation’ on encrypted messaging services such as Telegram, where they are consumed en masse.

Harun Farocki wrote that operational images are not ‘intended to entertain, instruct or sell’. However, the use value of operational images from the Ukrainian war frees them from these limitations: when edited into films of military operations such as those produced by certain Ukrainian or Russian combat brigades, operational images – inserted by editing into a fabric of images of operation – can then entertain when consumed by enthusiastic warwatchers, educate about the violence of the fighting and its outcomes or sell by demonstrating the effectiveness in operations of the military or civilian technologies that produced them. In addition, they can be used to raise funds, recruit volunteers or work on propaganda operations. In this way, the successive remediation of these images installs them in people’s minds: scattered, they are engraved in visual memories and now lie dormant in people’s minds.

The original article will appear in French in the issue ‘Images opérationnelles : agencements utilitaires des images en mouvement’ of the journal Images secondes http://imagessecondes.fr/. It was translated from French into English by the author, with the help of translation software.

Olivier Zuchuat is HES associate professor in the film department at HEAD – Geneva (HES-SO). A director and editor, his film credits include Djourou (2004), Far from the Villages (2008), Like Stone Lions at the Gateway into Nights (2013) and The Perimeter of Kamsé (2020), all of which have been released in Europe. As a researcher, he is the author of Attraits de la durée. Plans perdurant et montage intra-plan dans le cinéma contemporain (2025) and co-edited the books Montage – Une anthologie (1913-2018) and Lav Diaz: faire face.

Footnotes

[1] Original text : ‘1991, aus dem Golf-Krieg gab es solche Bilder zu sehen. Bilder aus der Luft. Im Zentrum das Fadenkreuz. Auch Bilder aus dem Kopf des Projektils, aus Kameras, die sich ins Ziel stürzen‘.

[2] Harun Farocki, ‘Phantom Images’, Public, n° 29, 2004, p. 17.

[3] Original text: ‘Solche operativen Bilder müssten doch eine andere Sicht auf die Welt eröffnen, von der sie etwas zeigen. Sie gehören zu einer anderen Gattung als die Bilder zu unterhalten, zu belehren oder zu verkaufen und müssten sich von diesen unterscheiden wie das Lastpferd vom Reitpferd‘.

[4] Volker Pantenburg, ‘Working images: Harun Farocki and the operational image‘, in Jens Eder et Charlotte Klonk (dir.), Image Operations. Visual Media and Political Conflict, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2017, pp. 57-58.

[5] Ibid., p. 58

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Dork Zabunyan, ‘Images from Ukraine: Who Really Wants the War to End?’, Harun Farocki Institut, May 26th, 2023 — Rosa Mercedes / 05 . Online: /en/2023/05/26/images-from-ukraine-who-really-wants-the-war-to-end-2/ .

[8] The expression ‘warporn’ has become part of common parlance, just like ‘foodporn’, to the point where there are now communities on the reddit forum called r/Militaryporn or r/coldwarporn, with hundreds of thousands of members.

[9] The organisation Drones For Ukraine (https://www.dronesforukraine.fund/ ), for example, finances the purchase of civilian drones for Ukrainian troops, in return for which it provides donors with small pieces of the wreckage of Russian military aircraft and helicopters (SU-34, MI-24 or KA-52 models) that have crashed on Ukrainian soil.

[10] Dominika Kunertova, ‘Drones have boots: Learning from Russia’s war in Ukraine’, Contemporary Security Policy, 44:4, 2023, pp. 576-591. DOI: 10.1080/13523260.2023.2262792

[11] For further details, please refer to the manufacturers’ promotional websites: https://www.avinc.com/lms/switchblade-600 et https://zala-aero.com/en/product/izdelie-52/.

[12] Cf. ‘Killer Drones’ The Economist (London), vol. 450, no. 9383, The Economist Intelligence Unit N.A., Incorporated, 2024, p. 7.

[13] Cf. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-65389215 or https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/30/technology/ukraine-russia-war-drones-china.html

[14] Manufacturer’s website: https://baykartech.com/en/uav/bayraktar-tb2/.

[15] Cf. Roger Nathan, Image ware-fare in the war on terror, New York: Pallgrave MacMillan, 2013

[16] Volker Pantenburg, ‘Working images: Harun Farocki and the operational images’, op. cit., pp. 57-58.

[17] Here we use the term ‘invisual’ defined by Jussi Paprikka in Operationnal Images. From the visual to the invisual, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2023, pp. 22-24.

[18] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation. Understanding New Media, Cambridge (Massachusetts), The MIT Press, 2000.

[19] Nathan Roger, Image Warfare in the War on Terror (New Security Challenges), London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, p. 48.

[20] Cf. Anna Leander & Olivier Zuchuat, ‘Mediating Operational Images. Visibilizing the ‘Invisual’ in the Ukrainian War’, in preparation, 2026.

[21] Cf. James Der Derian, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network, New York, Routeledge, 2009. Robin Andersen, A Century of Media, A Century of War, New York, Peter Lang, 2006, or Haidee Wasson et Lee Grieveson (dir.), Cinema’s Military Industrial Complex, Oakland, University of California Press, 2018.

[22] Roger Stahl, Militainment, Inc.: War, Media, and Popular Culture. London, Routledge, 2009.

[23] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/10/ukrainian-film-makers-military-drone-operators-donetsk .

[24] https://www.facebook.com/oleg.sentsov . Post dated 20 October 2023 at 15:08. Accessed on 9 April 2024.

[26] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trLOpGU_MMM&rco=1

[28] Part 1: Bridghead . Posted on 24 July 2023(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RtezbxukS6A&rco=1 ). Part 2: The way forward. Posted on 14 October 2023(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FompoLbNB_8&t=215s ). Part 3 : Andriivka is ours. Posted on 4 February 2024 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZyhOLdsPcE&t=1293s ).

[29] https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-ato/3659853-azov-becomes-separate-assault-brigade-with-armys-ground-forces.html

[30] ‘The Third Separate Assault Brigade is a volunteer unit formed in the early days of the full-scale invasion. The founder is the first commander of the Azov regiment Andriy Biletskyi. The Third Separate Assault Brigade was formed on the same principles on which the legendary Azov and the entire Azov movement are based. The foundation worldview principles of the Azovian units are Ukrainian-centrism, traditionalism, hierarchy and responsibility. After passing a difficult selection, only highly motivated and strong-spirited fighters, ready for constant improvement and tough battles with the enemy on the front line, enter our ranks’. (Online: https://ab3.army/en/about-the-brigade/ . Accessed: 1 April 2024). While the Azov Battalion openly included neo-Nazi militants in its ranks in 2014-2015, the 3rd Assault Brigade seems to be publicly distancing itself from this legacy.

[31] These shelters are called ‘blindage’ by the Ukrainian army.

[32] We refer in particular to the use of slow motion in Sam Peckinpah’s films, as analysed by Stephen Prince (‘The asthetic of slow-Motion violence in the films of Sam Peckinpah’, in Screening Violence, Stephen Prince (ed.), New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press, 2000, pp. 165-23).

[33] Mykyta Kryvocheiv, personal communication.

[34] Cf. Alexander R. Galloway, ‘Origin of the First-Person Shooter’, Gaming. Essays on Algorithmic Culture, Electronic Mediations, Volume 18, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2006, pp. 49-68.

[35] The feature film The Anderson Platoon (1967), directed by Indochina War veteran Pierre Schoendoerffer during operations carried out by the US Army’s First Cavalry Division in South Vietnam in 1966, was one of the first films to document infantry combat over time and to be made public (Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film, 1968).

[36] Cf Stephen Prince (ed.), Screening Violence, op. cit, in particular the articles in the section ‘The Aesthetics of Ultraviolence’

October 14th, 2025 — Rosa Mercedes / 05