Driving on sight vs Seeing the light

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and German Chancellor Angela Merkel during European heads of state and governments summit at the EU Council headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, 25 June 2015 (EPA, Olivier Hoslet)

Referring to her method of dealing with the Greek economy in June 2015, German chancellor Angela Merkel used a formulation that should quickly become one of the phrases to characterize her political temperament as a leader/navigator: “Man muss auf Sicht fahren,” we “must drive on sight”.

The metaphor evokes a ride through foggy weather when the driver is impelled to rely on her or his eyesight alone, rather than on any on-board computer assistance system. More precisely, driving on sight is reminiscent of manually conducting a train, “carried out at a speed that allows the driver to stop the train before reaching any obstacle on the track” (International Electrotechnical Commission).

In summer 2015 the fog in question was the situation in Greece (as perceived from the driver’s seat of the strongest economic power in Europe, in the position to dictate the terms of an, arguably, disastrous debt economy based on the principles of austerity measures imposed by the troika), and a few weeks later the “refugee crisis.”

Now, since February 2020, the same metaphor is in use again, this time deployed (more by the media than by the chancellor herself) to describe the way in which the Merkel administration is (mis)managing the coronavirus crisis. In the process, “driving on sight” has become an increasingly ambivalent formula. Those in favor of an attitude of patience and prudence welcome the lack of any long-term planning alluded to in the phrase. Whereas those critical of Merkel’s hesitant, tentative and reticent mode of governance exploit the negative connotations of the metaphor.

Carl von Clausewitz (1780 -1831)

Because “driving on sight” is a sibling of “blind flight,” the two tend to be treated as synonyms. In a similar vein, an article in the online journal Telepolis speaks of the German government’s “blind flight through the pandemic.” Likewise, Derek Thompson in the Atlantic evokes “the fog of pandemic,” drawing on Prussian military analyst Carl von Clausewitz’ vintage metaphor of the “friction and fog of war.”

Battlefield 1, 2016, Electronic Arts

Other than Trump or Macron, Merkel has been cautious not to fall back on the (male) rhetoric of war and take rescue in any Clausewitz tropes. However, “driving on sight” in a pandemic is a response that could have been learned exactly from someone like Clausewitz, who wasn’t a typical militaristic macho, quite to the contrary. As historian (and conductor) Lars Straehler-Pohl explains: “War is always marked by the unforeseen. Clausewitz as an experienced major general calls these unplannable factors friction. The combatants see many things through a fog. There are many things they have to anticipate, estimate and adapt actions step by step, but at the same time quickly to the concrete situation. This approach has parallels to the fight against corona in the interaction between medical research, relevant disciplines, politics and social behaviour. However, vigilant observation and rapid action correction are always part of complex tasks.”

It needs to be said that Clausewitz in his posthumously published, 1832-34 treatise On War didn’t use the exact phrase “fog of war” (which premiered in a text, by another, lesser known, military expert from 1896). Rather, Clausewitz put it thusly: “War is the realm of uncertainty; three quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.” [“Der Krieg ist das Gebiet der Ungewißheit; drei Vierteile derjenigen Dinge, worauf das Handeln im Kriege gebaut wird, liegen im Nebel einer mehr oder weniger großen Ungewißheit. Hier ist es also zuerst, wo ein feiner, durchdringender Verstand in Anspruch genommen wird, um mit dem Takte seines Urteils die Wahrheit herauszufühlen. Es mag ein gewöhnlicher Verstand diese Wahrheit einmal durch Zufall treffen, ein ungewöhnlicher Mut mag das Verfehlen ein andermal ausgleichen, aber die Mehrheit der Fälle, der Durchschnittserfolg, wird den fehlenden Verstand immer an den Tag bringen.”]

Dealing with uncertainty and the unpredictable, Clausewitz made quite clear, is a matter of intellect and reason, but even more so of a particular sensitivity for the truth (“die Wahrheit herauszufühlen”). That said, in a stage when even “‘black swan’ or unpredictable crises” cannot longer be mitigated by “prompt, wise and coordinated action” or by being “agile, flexible, innovative, indomitable, and gritty,” “true chaos leadership,” as management consultant Davia Temin argues in Forbes, demands a radically different approach than the one put forward by standard, run of the mill (or excessively narcisstic) political rule:

“In chaos causality is lost, strategy and leadership no longer work as well, and we are left powerless. And that is where we almost are now. So many different black swan crises (pandemic, financial meltdown, mass layoffs, soaring unemployment, untrustworthy leaders, misinformation everywhere) are crashing into one another, clumping together into a sticky, indistinguishable mass. It’s no longer quite as clear how to sort it all out. With leadership all but abandoned on the national level, with crisis management rules ignored, and misinformation everywhere, it’s no longer a certainty that even if we could put in logical fixes now, they would work.”

Temin advises to put trust into a guidance that navigates beyond both alpha voluntarism and mere rational behavior: “our own moral compass must guide us. […] True North becomes a sense of integrity, morality, courage and humanity. This beacon prizes kindness and compassion and rejects narcissism, sell-dealing, drama, liars and cowardice. It puts people first, without destroying the systems and companies that have always supported us, and will again. […] True Chaos Leadership rests on an inner sense of morality and direction in the face of utter pandemonium.”

In symptomatic contradiction to the relatively cautious leadership recently displayed by political leaders such as Merkel, Jacinda Ardern (New Zealand), or Sanna Marin (Finland), the “driving on sight” gets occasionally replaced by the umistakably delusional “light at the end of tunnel” metaphor put forward for instance by Donald Trump (in a tweet and live) on March 24: “I’m very proud to be your president, I can tell you that. There’s tremendous hope as we look forward and see light at the end of the tunnel.” James Farrows, a former speech writer at the White House, reminds us and Trump, again in the helpful Atlantic, of the historical semantics of the phrase “light at the end of the tunnel”:

“During [Trump’s] teenaged years and his early 20s, when hundreds of thousands of his contemporaries were being drafted for service in Vietnam, and when more than 50,000 of them were killed, those words were among the most infamous parts of the American lexicon. Like ‘it became necessary to destroy the town, in order to save it’—a possibly apocryphal phrase attributed to a U.S. military officer, about the scorched-earth policy—’light at the end of the tunnel’ came to symbolize the sustained folly of the war in general, and the illusion that success was near at hand. […]”

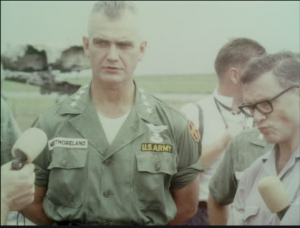

William Westmoreland (1914–2005), commander of United States forces during the war in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, and chief of staff of the US Army from 1968 to 1972

“During and after the Vietnam war, ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ became so familiar and polarizing that one of the most publicized libel suits of the era, in which four-star General William Westmoreland sued CBS News for $120 million, centered on these very words. As the New York Times reported during the trial, in 1984: ‘Gen. William C. Westmoreland and a lawyer for CBS argued yesterday over one of the most memorable phrases of the Vietnam War, with the lawyer suggesting that the general had misled Washington into believing there was ‘light at the end of tunnel’ in 1967 and the general saying he had not used that expression. ‘I never had quite that degree of optimism,’ General Westmoreland told the jury at his libel trial against CBS in Federal Court in Manhattan. But the lawyer, David Boies, showed the witness a Nov. 26, 1967, cable he had sent during a visit to Washington to his deputy in Saigon, Gen. Creighton W. Abrams, in which the phrase ‘some light at the end of the tunnel’ was bracketed in quotation marks.”

Staring at the fog (while driving on sight) and gazing into the tunnel (searching the light at its end) are different ways of seeing. They also render the appearance of things and situations differently. The optimisim of the latter may not be entirely absent from the hesitancy of the former, but in dismissing the hesitancy of the former the optimism of the latter turns dangerous. In other words, the fog in the tunnel needs to be recognized, not ignored.

Fog and anti-fog measures may come in unexpected forms though. Here are two examples to finish this off:

In late February 2020, the Philadelphia branch of NBC reported on Halosil, a local company in New Castle, Delaware. It produces the Halo Fog Disinfectant System, a fog machine supposed to be playing a role in fighting the coronavirus (in need of being fact-checked …);

in April 2020, Armasan Ambalaj, a packaging company based in the northwestern Tekirdağ province in Turkey, has turned to the production of anti-fog shields that reduce the effects of exhaled moisture; the company now manufactures 20.000 units a day to provide this item that is “crucial for frontline medical personnel treating COVID-19 patients and wearing the shields nonstop for hours” (likewise subject to potential further research …) TH

April 23rd, 2020 — Rosa Mercedes / 02