About the exhibition “We show what we (don’t) know – images as research”

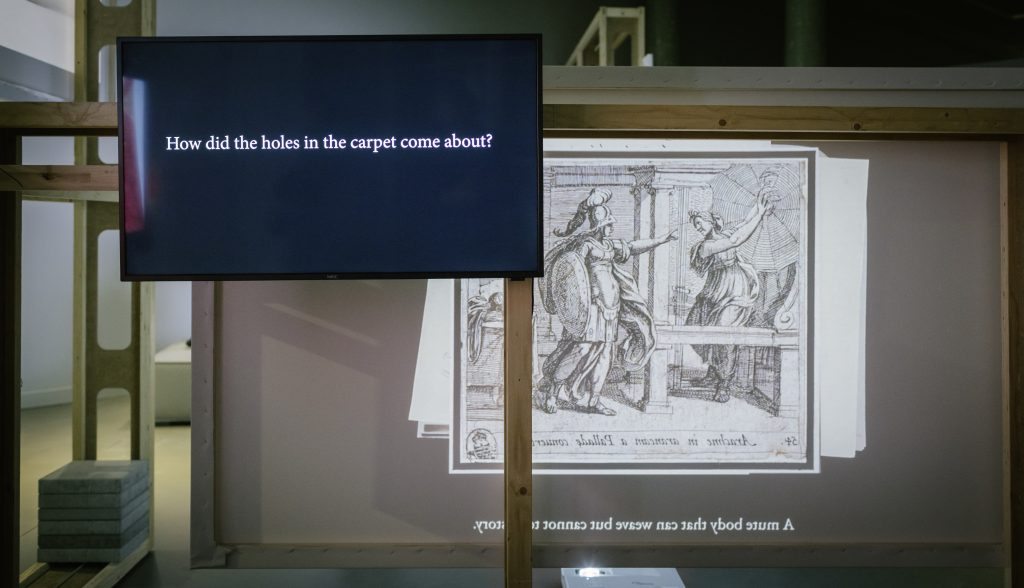

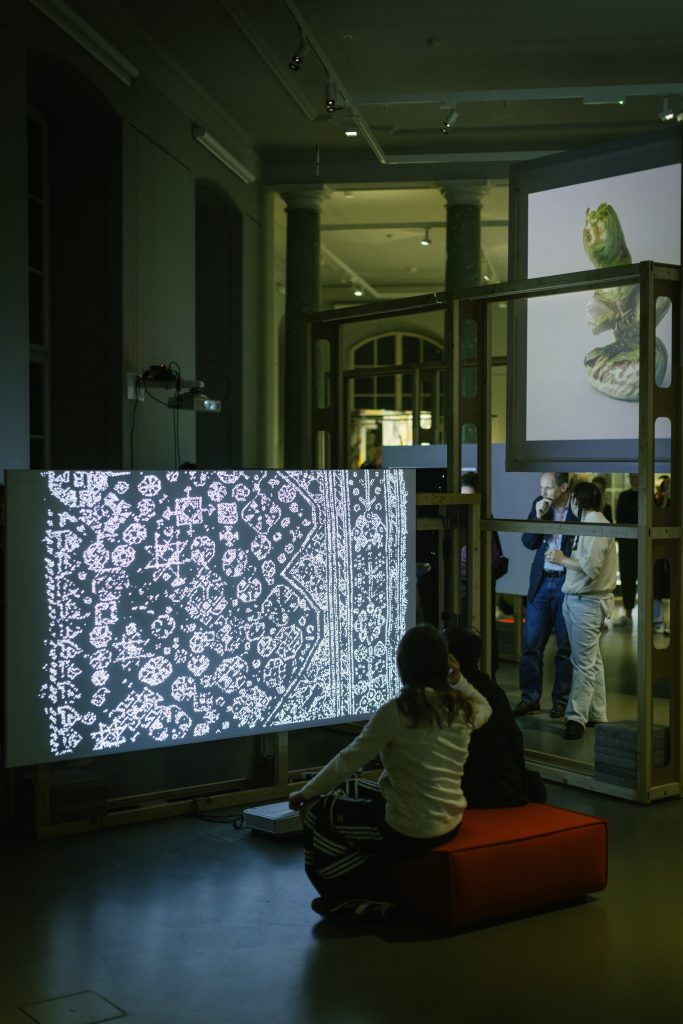

Opening of the exhibition ‘We show what we (don’t) know’ by the HGB Leipzig on October 12, 2023, at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections. Photo: Oliver Killig

A conversation by Lucie Kolb with Mareike Bernien, Doreen Mende, Anna-Lisa Reith and Clemens von Wedemeyer on March 27, 2024.

What images are created during research processes in a museum? What does scientific practice look like before the opening of an exhibition? How does knowledge become visible in the museum world? The exhibition “We show what we don’t (know) – images as research” was created around these questions. A project that brings together 16 new artistic works that deal with research in museums as an aesthetic practice.

Initiated by the Research Department at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (SKD), artists from the expanded cinema class at the HGB Leipzig met with numerous museum stakeholders over the course of a year: conservators, electricians, scientific staff, directors, X-ray technicians and provenance researchers from the SKD. In seminar sessions at the HGB, the young artists’ observations were reflected upon and questioned with regard to their own artistic practice – as visual forms and carriers of aesthetic-analytical categories of knowledge.

The resulting dialog between internal and external perspectives, between practical forms of the museum and the class of an art academy, unfolded in various research environments and could be experienced through a variety of forms of expression. Among other things, video installations, textiles, an imagined computer game, transformed angels, AI-generated porcelain and an interview with a pistol were created.

In reference to Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki’s “Labour in a Single Shot”, one could also say that 16 “Attitudes to Research” have emerged. Images that not only document, but also have a researching effect. Observing, organizing, interpreting, they recognize the museum as a place of knowledge and history production.

The aim of the seminar cooperation, which culminated in the exhibition “We show what we (don’t) know – images as research”, was to make scientific and research work in the museum visible as a creative process. Two questions were central to this: What images does research itself produce? And how can images, in both an artistic and documentary sense, themselves become tools of research? As if the images themselves could observe, analyze, comment or measure.

The exhibition brought the results of the dialog back to the site of the event, to the museum, and enabled the scientists and employees to see their own work through other images. The exhibition thus expands the understanding of museums and introduces a new image category. In addition to photo documentation and object photography on the one hand and the image format of the exhibition view on the other, the image of research is now also on display.

On display were artistic works by Anna Sopova, snc, Ingmar Stange, Johann Bärenklau, Katharina Bayer, Ksenia Sova, Leila Brinkmann, Lucia-Charlotte Ott, Mahshid Mahboubifar, Marta Sundmann, Natalia Zaitseva, Sijo Choi Kim, Simón Jaramillo Vallejo, Valéria de Araújo Silva, Yunseon Jeong and Su Yu Hsin.

The project was a cooperation of the HGB Leipzig, class expanded cinema, led by Clemens von Wedemeyer and Mareike Bernien, with the research department, led by Doreen Mende with Anna-Lisa Reith, at the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. The presentation was curated by Anna-Lisa Reith.

Lucie Kolb: The exhibition “We show what we (don’t) know – images as research” deals with art historical and conservation research in museums and asks how this work influences the experience of museum visitors. This question is particularly virulent and controversial against the backdrop of discussions about colonial heritage, looted art and restitution. The exhibition approaches the institution of the museum, itself in a state of upheaval, through practice and long-term work with the collections. I like the fact that it deals with the various infrastructural, logistical, legal and scientific practices in the museum and examines the specific places associated with them. What questions about museum practice were central to the exhibition?

Doreen Mende: For us, the research department at the museum, it was crucial to use this collaboration and ultimately this exhibition to break down the modernist separation of researching and exhibiting in the museum and to ask what images this separation creates as part of a research process. For some years now, exhibitions, including those at the SKD, have often featured an active restoration workshop or the documentation of a restoration, e.g. “Johannes Vermeer. Vom Innehalten” (2022) or the show restoration of “The Madonna of St. Sebastian” by Caravaggio (2022-2024) in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. We also asked ourselves to what extent the image of research is not just the famous look behind the scenes or over the restorer’s shoulder. Rather, to what extent the image itself could become an instrument of research, what this image would look like as research in order to capture the infrastructures of the museum as an architecture of knowledge production in a multi-layered way. We were interested in the spectrum of the visuality of research and the grammars of visual research as a category in its own right. By bringing together and linking research and exhibition, we also challenge the boundaries of the museum tradition of modernity and pose questions about the social mission of museums as places of knowledge production.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: The exhibition initially also opened doors for young artists, who were able to look behind the pictures and into the workshops of a large museum network. In their works, they trace the investigation of these objects by the researchers. The exhibition thematizes the gap between what visitors see in the museum and the research behind the scenes and thus undertakes a form of institutional critique of the museum as a hermetic space.

Anna-Lisa Reith: One of the artistic works is dedicated to radiation diagnostics – an imaging technique used in art historical research and conservation technology to allow us to look beneath the surface of paintings. Lucia-Charlotte Ott has applied this method to Marietta Tintoretto’s “Self-Portrait with Jacopo Strada (1507-1588)” together with the SKD’s X-ray technician. In her work, she reorganizes these X-ray images and produces supplementary, fictional X-ray images. In this way, the mostly hidden moments of museum practice, the discovery of overpainted areas or individual details, become visible in her artistic approach and the effect of scientific findings is conveyed.

Opening of the exhibition ‘We show what we (don’t) know’ by the HGB Leipzig on October 12, 2023, at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections. Photo: Oliver Killig

Lucie Kolb: The exhibition takes up approaches of institutional critique, in particular the idea of a new space that combines backstage and display. How is this concept applied in the exhibition, particularly in relation to the merging of the front and back of images and the different layers that are illuminated?

Mareike Bernien: For the exhibition display, it was important for us to create a spatial connection between the front and back of the images. The semi-transparent screens were mounted on scaffolding on the walls so that the projected films could be seen from both the front and the back. Based on the technique of transillumination, the films overlapped and commented on each other. The exhibition also raised the hypothetical question of what it would be like if the SKD were to make its walls invisible. This would make connecting lines between different disciplines and studies visible, but also what is otherwise made invisible in representation, namely the reverse side of the images, which is essential for provenance research, for example.1 This was also one of the approaches of Ingmar Stange’s work, which was dedicated to precisely this invisibility of research in the museum, focusing on provenance research and combining it with the work of illuminating the museum. Stange shows the work that happens around the picture as research activity, but also as installation activity, which repeatedly recedes into the background and is made invisible. Understanding the equivalence of these processes and the painting itself as a process was one of the exhibition’s approaches.

Doreen Mende: The preservation and conservation research of the collection holdings – paintings, sculptures, objects, photographs, video works, installations – is one of, if not the most important pillar in the museum. At the same time, it is important to understand that research-based conservation is a fluid process. It is determined by the people working with the objects. Each generation sets its own priorities, contexts and uses the further development of imaging technologies. The artistic works created here are able to make these processes visible, to think about their pictorial qualities and thus to reflect on the institutional work at the museum from a visual perspective. At the same time, the exhibition reflects these considerations back to the people who are involved in the processes at the museum. This is an important process of reflection using images – not ‘just’ as objects of study, but as instruments with their own analytical power.

Mareike Bernien: Another work that deals with the museum infrastructure is Su Yu Hsin’s “Die Fluten”. In it, she deals with the hygrograph, a humidity control instrument commonly used in museums to control the indoor climate. The hygrograph she adapted recorded the fictional curve of a flood, which on the one hand may refer to the flood of 2002, but also raises questions about the ecology of the museum and the energy consumption of an artificially generated indoor climate. Anna Sopova’s work, on the other hand, examines museum security techniques, including glass display cases and motion detectors, which are used to maintain the distance between objects and visitors – at the same time, she directs the museum’s gaze away from objects and towards the regulation and navigation of the public.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: Johann Bärenklau visualized the sounds of the museum by playing them from the surfaces of empty display cases, thus also representing the body of the museum as a surface. With a focus on materials, Valerio de Araújo Silva thematizes the marble of a sculpture, Nicolas Cordier’s “Junger Afrikaner”, which depicts a person of colour. Other works, such as those by Sijo Choi Kim and Leila Brinkmann, explored the psychology of museum employees and their motivation to preserve objects and not destroy them.

Anna-Lisa Reith: The walls of the museum can quickly create a closed knowledge system that requires specific training or specialized expertise. This makes it all the more important that we think about the museum internally and at the same time think beyond it together. The knowledge of experts is enormously valuable, so we need to create hubs to make this knowledge accessible to a wider audience, as well as artists and researchers. The aim is to further develop the museum as an open, relevant place for society. This is a task that we have also taken on with this exhibition and that we are continuing to work on.

Opening of the exhibition ‘We show what we (don’t) know’ by the HGB Leipzig on October 12, 2023, at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections. Photo: Oliver Killig

Lucie Kolb: The exhibition focuses on the artistic tracing and visualization of research-based, infrastructural and institutional work in the museum. However, the subtitle of the exhibition “Images as Research” also makes it clear that it is not just about research in the museum, but also about visual processes as research. How can the practice of visual research be described? What knowledge is generated through this artistic research that cannot be generated through museum work?

Mareike Bernien: For us, it was important to find the balance between images about research and then also images as research. Images not only document, but also conduct operative research. This means that research and arguments can be made not only about, but also with images. In addition to factual knowledge, such methods of artistic research can also employ means of speculation or fictionalization. Biographical and physical knowledge, which is often excluded from traditional scientific approaches, can also be included. A good example of this is Mahshid Mahboubifar’s work “Too Much Past Is a Dangerous Thing”, which was created in close collaboration with the textile restorer Christine Müller-Radloff. While Christine Müller-Radloff asks what remains of the carpet and how it can be reconstructed, Mahshid Mahboubifar asks what narratives have been lost in the process of museumization. This collaboration made it possible to reconstruct the carpet, taking into account both technical and narrative aspects, including the artist’s biographical knowledge. The work shows how artistic and scientific perspectives can come together in a reconstruction project that encompasses not only the material and the visible, but also the gaps, the invisible and that which is made invisible by the museum.

Lucie Kolb: What tools or experiences are needed for this kind of visual research? What impulses come from artistic research in order to re-localize museum work?

Anna-Lisa Reith: In the work “Roar of Combat 3 – Return to Tradition”, snc uses the artistic potential of gamification. snc has developed a computer game that turns the armory of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen into an interactive setting. Fictitious avatars roam the collection in first-person mode, select weapons and comment on what is happening, comparable to a Twitch livestream. In this way, the game combines the representative presentation of historical weapons with current social issues relating to violence, power and aesthetics.

Seemingly distant subject areas such as museums and gaming enter into a dialog with each other, creating surprising approaches for a critical debate. At the same time, the project illustrates how closely the issues are actually interwoven. With Roar of Combat 3, snc questions the boundaries of classic exhibition practice and expands them to include participatory, digital perspectives.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: Natalia Zaitseva has also worked in the armory. In “Interview with a Pistol”, she made a pistol speak. She gave the pistol a biography and conducted an interview with it. This approach encouraged viewers to look at themselves and the museum from the perspective of the object. Digital tools were also used to speculate new forms: Simon Jaramillo Vallejo trained a machine-learning system with images of porcelains, which produced new figures from them, Ksenia Bashmakova digitally altered an Erzgebirge angel in a cubist manner.

What I found significant about the artists’ work was that many of them were interested in the Museum of Saxon Folk Art. This is where a different form of research, citizen research or research “from below”, from the so-called people, becomes visible. There, socio-psychological and site-specific questions relating to Saxony become visible, such as the image of women and culture in the Ore Mountains. Leila Brinkmann deals with images of women and their roles, especially as housewives and mothers. By taking macro photographs of the exhibits, she attempted to trace the roles that have been collected over the last few centuries and have thus become official. Such works raise important questions about the definition of folk art and its connection to contemporary and other art practices.

Anna-Lisa Reith: Leila Brinkmann’s work also had a remarkable effect on mediation work. Women between the ages of 50 and 65 in particular stopped to look at the macro photographs showing objects from their childhood. The focus was on toys that served to educate girls and embroidery patterns from needlework books. Through their visual presentation, the visitors were able to remember their own childhood and reflect on the function of the toys, rhymes and work in their own upbringing without being explicitly pointed out.

Doreen Mende: In many of the artistic works, the practice of reconstruction as a method plays an important role. Reconstruction serves not only to historicize, but also to visualize a way of working and thus to situate it in the present. This approach was the basic premise of our collaboration: how can we develop methods that enable us to turn the concept of the museum as a place of historicization on its head in order to question the narratives of the collection holdings with regard to their future potential. We often talk about learning from the collections as cultural heritage for the future. But what does that mean? How are past and future intertwined in the present in this learning process and, above all, what knowledge does this transhistorical interweaving produce? The Transcultural Academy 2023 took place under the question of “futurities”. Futurity here is not a utopian or modernist concept that says we are making a tabula rasa and imagining a new, promising future, although one would wish for nothing else in these turbulent and difficult times. Rather, it is about an examination of historical contexts, historiographies and inscriptions as unfinished, open, polyphonic and multi-layered processes. In this respect, I would say that the method of reconstruction makes it possible to approach the collections as repositories of knowledge, as archives of historiographies with the scientists at SKD – in other words, to take history lessons with the objects and to place them in relation to pressing questions of society and the present in order to imagine their futures as an archaeology of the future. How would a scientist or artist look at our current research questions in 100 years’ time? Mobilizing futures therefore means not throwing out the significance of historical work with the bathwater of euphoria about new perspectives, but – on the contrary – bringing them into conversation with each other.

Opening of the exhibition ‘We show what we (don’t) know’ by the HGB Leipzig on October 12, 2023, at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections. Photo: Oliver Killig

Lucie Kolb: The exhibition was created over the course of a year in cooperation between the expanded cinema class at the Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig and the research department of the Dresden State Art Collections. How did the collaboration and its specific architecture come about? What possibly instituted the collaboration, especially with regard to the question of the necessity of creating a basis in the museum to present history as an unfinished process and to bring different imaging processes into a dialog with each other?

Clemens von Wedemeyer: The expanded cinema class at the HGB was founded with the aim of teaching moving images in the visual arts, but also to dissolve the boundaries of traditional forms, to look behind the screen and, for example, to consider the making-of as an actual project. The class has carried out several site-specific projects in recent years, including a collaboration with the SKD at the GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde in Leipzig (‘fremd’, 2016) and an exhibition at the Villa Esche in Chemnitz (2021), where the collections were used extensively and contemporary art was installed in historical locations.

Doreen Mende: For the SKD, two main strands are important in the collaboration between the expanded cinema class and the SKD. On the one hand, it is about dealing with the image as subject and process, inspired by the work of Harun Farocki and Antje Ehmann. Hence the interest in reflections on the image as a visual category and the question of the “making-of”.

On the other hand, there is a need to create a platform for transdisciplinary research in the form of collaborations that functions as a place of learning, teaching and knowledge exchange. When we started the project, I thought that the exchange between scientists and artists, especially the generation of students at an art academy, had already taken place many times at the SKD. With a group of 16 students in the workshops, it became clear that it was both an enormous logistical challenge and an immense enrichment. The main task of the Research Department was to establish conditions of mutual trust across the collections and to continuously ensure in daily practice that it is not about replacing historical or institutional knowledge, but about learning together. Anna-Lisa’s coordinating and communicative work was extremely important in creating trust in the collections through regular internal discussions and establishing a dialogical atmosphere with the students. It is a sensitive process, especially as the range of tasks often extends beyond the existing positions, particularly in the museum context. It was therefore necessary to make it clear that it cannot be a question of re-learning or new learning on the part of the museum, but rather of the openness of dialog and listening as a knowledge process that makes it possible to learn from one another. At the same time, Clemens and Mareike supported the artists in their class at the HGB.

Mareike Bernien: Anna-Lisa did a lot of mediation work between the institutions. She endured conflicts and put different languages in relation to each other throughout the production process. We helped the students to understand what it actually means to work with an institution and to retain a certain degree of autonomy. That was another area of learning.

Anna-Lisa Reith: In particular, access to the objects in the depots and workshop spaces requires detailed coordination and a lot of time in order to meet structural requirements and define clear expectations. Communication difficulties often arise between artists and institutions due to different ideas and languages. My main task was therefore to pass on the individual interests of the artists to scientists and SKD staff, to interpret, to establish individual connections and, above all, as already emphasized, to build a sense of security.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: The project was perhaps only possible through the participation of students or young artists, as they have a very special relationship with the institutions and are more likely to bring with them a scope for experimentation and crossing boundaries. A certain callousness, because you have nothing to lose at first or because you are doing something like this for the first time and want to know how far the boundaries can be stretched or crossed. And those who were so active also radiated that they had no bad intentions… this was helpful in building trust and avoiding misunderstandings.

Opening of the exhibition ‘We show what we (don’t) know’ by the HGB Leipzig on October 12, 2023, at the Japanisches Palais of the Dresden State Art Collections. Photo: Oliver Killig

Lucie Kolb: It is interesting to see the groundwork that needs to be done behind the scenes to establish trust, to translate and communicate, to create conditions and to link different knowledge practices. What did you take away from the collaboration? What can this kind of work with a collection trigger, especially with regard to the promotion of research-based image processes? And what effect did the collaboration with the artists have on the SKD staff?

Mareike Bernien: From my point of view, the collaboration in the research group was particularly enriching, as there was a comparatively long period of time available for a project at an art academy. This allowed us to develop individual questions and learn together. In some cases, the exposés were exchanged and someone else made suggestions as to how to proceed. Regular communication about ideas sharpened our view of the context and enabled us to develop individual research approaches.

Anna-Lisa Reith: By bringing together external and internal knowledge, the anchoring of the artworks created in the exhibitions is a great benefit – for example, the Armory is now showing the film “Interview with the Pistol” by Natalia Zaitseva in its rifle gallery. The institution’s openness to dealing with complex questions about its collections from the outside shows a growing willingness to engage in dialog and to further develop its mediation. This gives hope for the sustainable establishment of collaborations and projects of this kind.

Mareike Bernien: There was a situation during the installation of the exhibition when the people who normally set up the lighting for the paintings helped to set up the exhibition. Ingmar Stange portrayed exactly this work of a lighting technician and his film ran in the room during the installation. The lighting technicians recognized the person being filmed. And there was suddenly a connection and also an appreciation of their own work, which I found very touching. I liked that.

Perhaps a comparison can be drawn here between the research work at the SKD and artistic research, which is often delegitimized by the sciences, and which at the same time promotes research but also questions it. It is worth taking a closer look at this area of tension, because I believe that this is precisely where knowledge takes place.

Lucie Kolb: This movement between valorizing and questioning museum work seems central to the exhibition. There is also a friction here between different forms of expertise and participation.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: When you leave your own studio as an artist:and enter into institutional contexts, you give up a kind of autonomy. It’s a balancing act between autonomy and the willingness to be instrumentalized in order to get something out of it for yourself. Looking behind the scenes and into the depots is a kind of trade in the interests of both sides. At the same time, a look into the depots reveals the discrepancy between the wealth of collected objects and what is on display – a challenge that many museum employees are confronted with. The museum is an interesting overload.

Footnotes

1 On the relationship and interplay between the metaphorical front and back of images, see also Hito Steyerl, “The Color of Truth,” 2008, p. 31 ff. 1

August 19th, 2025 — Rosa Mercedes / 09