HaFI 023 [Document]: Vademecum by Luciano Fabro

Given that Luciano Fabro, despite having consented to the idea of a film being made about his work, had no desire to be interviewed, I was forced to find another way to get him to talk despite himself. So I took advantage of the Vademecum he had written and distributed to the visitors to his exhibition at the Centre Pompidou and conceived of the idea of a voice-over that would guide not only my cameraman, but also the viewers of the film. (T.W.D.)

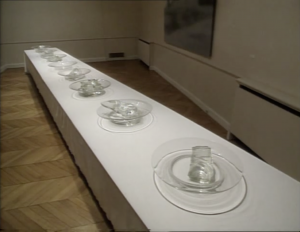

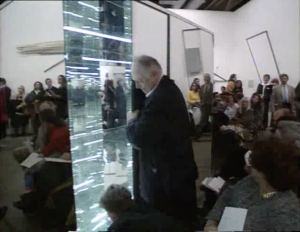

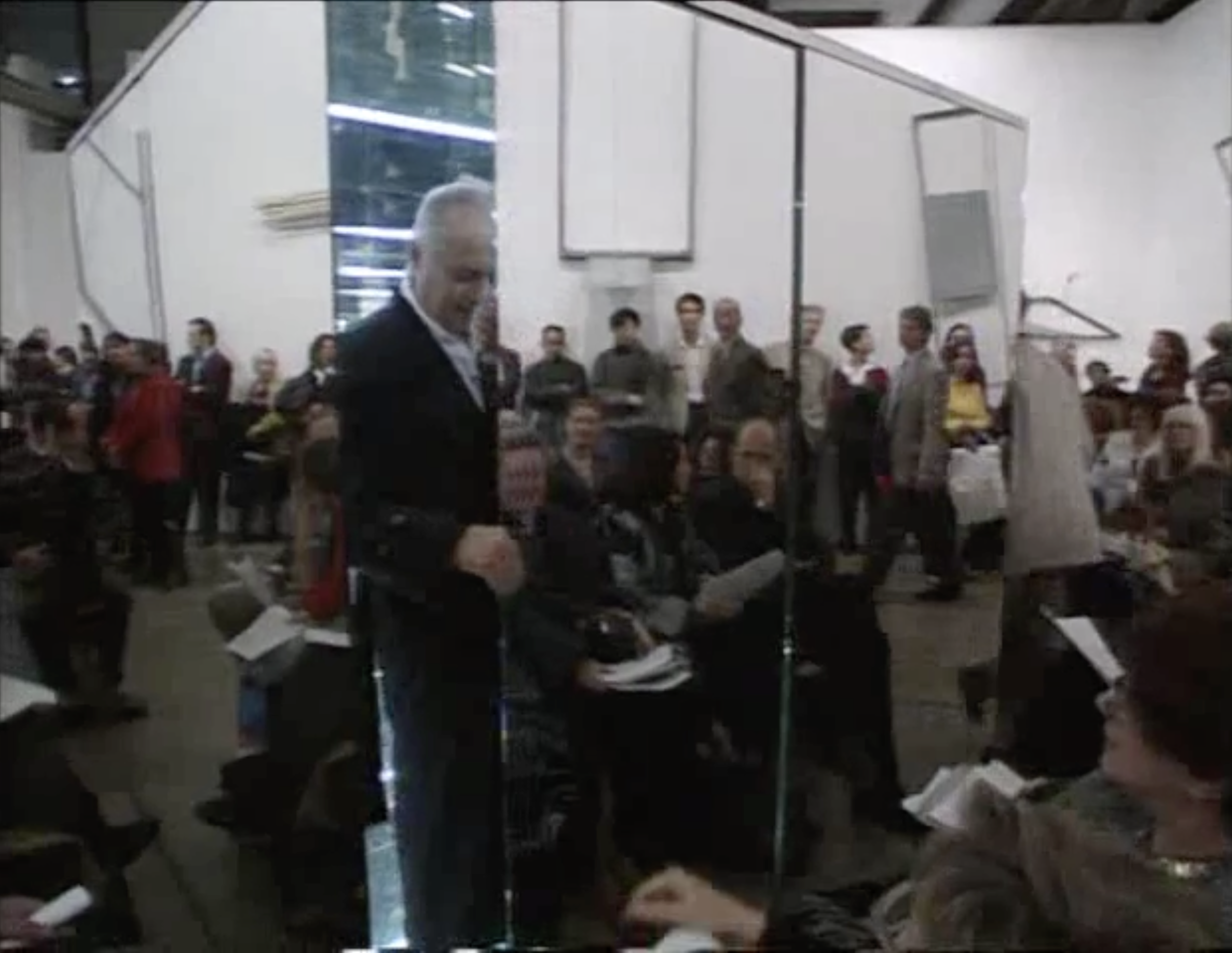

The following text contains the filmmaker’s voice-over in her documentary Luciano Fabro : Vademecum, produced by Les Films d’ici, Paris Première, France 5, and the Centre Pompidou in 1996. The illustrations are screenshots from the parts of the film showing the Paris exhibition of the artist. (C.B.)

Look out, it’s about to start. Keep the camera on Fabro, frame him as best you can: it’s the event that counts. You’re the very first person to see this film, since it’s your eye that’s behind the camera. Focus on the Vademecum. It’s an instruction manual of sorts that Fabro wrote for the exhibition. I’ll read snippets of it to you as I go along, so that you can really feel like you’re involved.

While he’s talking inside his cube of mirrors, let’s take this opportunity to film the exhibition.

It may not look like much, but this cube represents the dawn of an entire process of reflecting on our Habitats. . . as well as on space and perception. Do you think you could get inside the cube with the camera? That’s what the visitors are meant to do. Later on, I could superimpose some old photos showing how Fabro constructed the initial Habitat in his own size. Don’t change the frame, the superimposed images will blend with photos of the Ostinato: another of Fabro’s works in which he plays with his own body, but this time by making it disappear.

The next room is the “most exciting of the whole exhibition.” Fabro calls it the “Science Room.” Here, this artwork will make our job easier. Mind your shadow! —You see, these are among Fabro’s earliest works. They appeal directly to the viewer. As you can see, these reflective effects and transparencies are only activated if someone is present. Let him pass through the frame. Indeed, everything is moved out of frame here. I think it’s clear that these pieces are all about the interaction that is woven between the viewer, the artwork, and the artist.

These works are titled Attaccapanni, which means “coat hangers.” Fabro claims to have made them in honor of Manet, Degas, Monet, and Cézanne. It’s his way of thanking them for saving painting from the official academic art, L’art pompier. But maybe they’re just reflecting light.

Don’t you think we’ve worked hard enough? Come on, let’s get some fresh air.

Fabro made these Attacappanni artworks for Naples. He explains that, with them, he is confronting two of his greatest ambitions: “to accept the close of a wonderful day and […] to endure the advent of a new dawn.”

You work with light, don’t you know that our perception of color changes according to our latitude? These Attacappanni appear to have different colors depending on the country where they’re hung.

For Fabro, a Habitat is a place of harmony: you have to feel good there. This one is also an exhibition space for the artworks Fabro calls his Jewels. Fabro has also said that the Aachen Habitat is based on his idea of the Mausoleum of Theodoric in Ravenna. Ever heard of it?

Coreografia, also a Habitat. Move towards it slowly, [you] mustn’t lose the illusion of depth. Fabro has made some thirty interpretations of Italy, like this Golden Italy, and here, he has staged a few of them in this choreographed display. There’s Italy – The Road Map, Italian Nation, then Italy in Furs. He calls this one Italy of Pain, and then there’s Italy’s Mirror, covered by [flexible] strips [of lead].

Pier Paolo Pasolini, could you read? Ossip Mandelstam, Giordano Bruno, Malcom X, Olympe de Gouges. Fabro is always quoting Saint Matthew when he talks about this iconographic artwork: “I want the head of John the Baptist in a basin”—but I think what he really wanted to illustrate was that violence inflicted upon the body constitutes violence against the soul.

You can see why Fabro thinks these shapes are reminiscent of nudes. Frame them well, like you did earlier on with the metal rods of the Mikado. Here, Fabro has once again adopted the primary colors of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie, and that boogie we can hear here is part of the artwork. Then he introduces the theme of Nude Descending a Staircase, which he appropriated from Marcel Duchamp. You know what he says about that? That he’s just like virtually everyone else at that age: “making artworks based on other people’s ideas.”

Frame those feet, the Piedi, Fabro made them to explore the plastic properties and potential of different materials: marble, bronze, silk. And also the scope of the horizontal and the vertical. “These feet are not just one idea,” says Fabro, “they’re all your ideas.”

You’ll need to frame this bit very precisely. Nadezhda—that means “hope” in Russian. Try to render the beauty of the edge. It’s like a Fontana slash, or one of Barnett Newman’s zips. Try to show how the corner of the stone has been carved into the shape of an obelisk and then put back into place, but not exactly where it was. That’s it, let’s turn around. Slowly, but not sluggishly. Why do you think Fabro polished one side and not the other? He does that a lot. You can’t be sure if the stone’s obstructing the book, or if the book’s holding the sculpture in place. Tighten the frame even if you can’t read the title. It’s Hope Against Hope by Nadezhda Mandelstam, the wife of the great Russian poet. In it, she describes witnessing her husband’s death in a Soviet internment camp.

These are the obelisks, the Obelischi: Phidias, Praxiteles, Donatello, Michelangelo, Canova. Did you see that? Fabro describes this work as “unstable stability.” He says he didn’t look at these great sculptors as role models, but he did consider them all to be remarkable.

We come now to the Infinito: the sign of infinity. Here, I’ll read it to you: Fabro says that if you look at this work for long enough, it ends up seeming as if it were suspended above the ground, so don’t be alarmed if it induces a slight sense of vertigo.

Move forward slowly, but not too slowly. Let the artwork fill the frame. You can change the camera angle if you like, but try to maintain the coherence of the space as a whole. We need to be able to make out what’s written on the map of the sky.

Do you know where the design of the torn sheets comes from? Fabro modelled it on the plot lines drawn by Laurence Sterne in his novel Tristram Shandy to illustrate a course of events. But it’s also a life line. That’s surely why the work is titled Such is Life, Such is History, Such is Morality.

[It] would appear that this piece was inspired by an old instrument used for surveying, from which it also takes its name: Groma. Do you know what it was used for? The Romans used it to survey their military camps, and even their cities. Now you know everything.

What are you doing in here? Trying to take over where Fabro left off? Now you’re really going a bit too far.

Editorial note:

All the screenshots are from the film Luciano Fabro : Vademecum (1996) by Teri Wehn Damisch. (c) Teri Wehn Damisch/Les Films d’ici, Centre Pompidou (Service de la production audiovisuelle), Silvia Fabro. The English post-editing and proofreading of the French text was carried out by Louise Pain for Gegensatz Translation Collective. We would like to thank: Silvia Fabro and Céline Païni.