Channeling Disjunctions: Reflections on Inauthentic Empathy

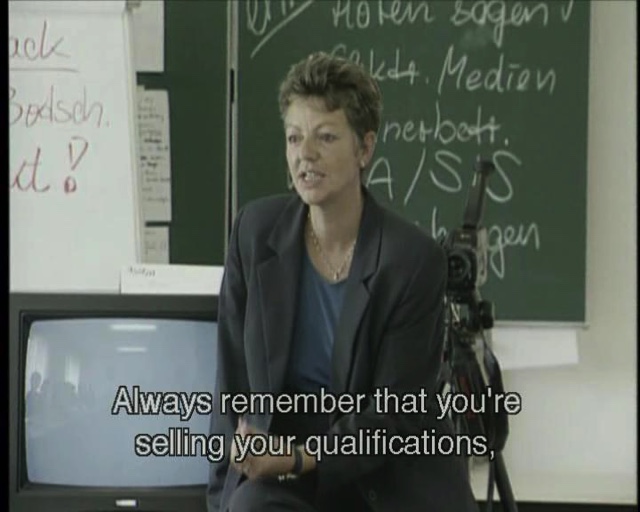

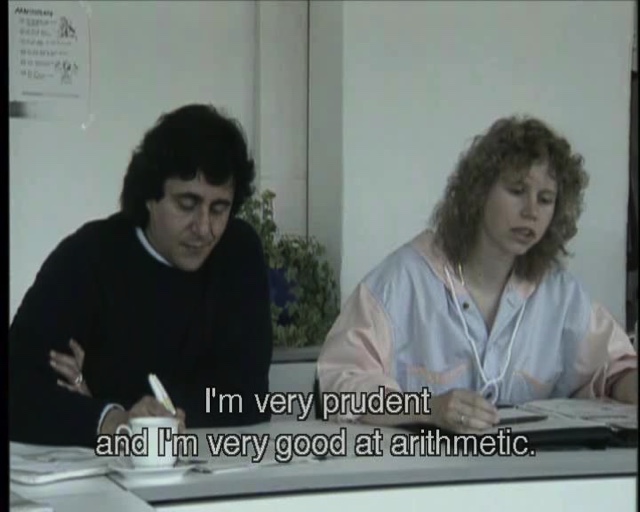

By recognizing and criticizing contemporary forms of exploitation of empathy within the neoliberal work market, Glenn Diaz exposes his novel’s characters to “something that blurs the line between the put-on empathy and the stirrings of the real one.” In doing so, he moves beyond widespread conceptions of empathy oscillating between a “natural,” good quality—empathy as a solution to disagreement and social injustice, as if coinciding with someone else’s feeling is itself already an end point —or a skill to improve in order to meet the requirements of emotional labor. Neither an act of magical attunement nor an infallible tool with which to understand and predict the needs of the client. Over the last twenty years at least, the term “empathy” has been circulating widely, and been overused: in academia—especially in analytic philosophy and in the cognitive field—as much as in the contemporary political lexicon, in art practices, and, of course, it has had an enormous impact on media strategies. Nonetheless, its meaning is often taken for granted and merely overlapped with the capacity for recognizing, feeling, and understanding someone else’s emotional state. In Zero Degrees of Empathy,1 Simon Baron-Cohen states: “Empathy is our ability to identify what someone else is thinking or feeling, and to respond to their thoughts and feelings with an appropriate emotion.” Here, the adjective “appropriate” resonates with the “empathy protocol” in the Utelco Manual Diaz describes—a manual used by the company AT&T to train their call center workers in the Philippines. The proliferating definitions and approaches to empathy, in most cases, cannot escape reinforcing the opposition between the rational sphere and the affective dimension. This is, for instance, the case with psychologist Paul Bloom in his book Against Empathy: The Case of Rational Compassion,2 where the author claims that mainstream theories of empathy assume that we tend to empathize more with those whose needs are salient, who are similar to ourselves, and who are close by in space and time. And furthermore, that empathizing with a person in pain or distress is to feel what the other person is feeling. This attitude, continues Bloom, can lead to an egoistic drift where the empathizer becomes more concerned with alleviating their own distress than with caring about the other person’s feelings or well-being. If Bloom’s analysis has the merit of unveiling clichés and ambiguous features of empathy as a guide for moral reasoning, he seems, however, to call upon a “rational version” of empathy, which consists in an objective analysis of costs and benefits, with a sympathetic but detached and dispassionate concern for the well-being of others. In her seminal book Scenes of Subjection,3 Saidiya Hartman offers a more careful, historically grounded, and less dichotomic criticism of the hierarchies hidden by Western narratives of empathy in the context of racial subjugation during slavery. Hartman has foregrounded the risk of reifying the categories of “empathizer” and “sufferer,” which reproduce dominant relations of power and reinforce the dichotomy between the emotional and rational dimension. A critical stance that has been followed also by Carolyn Pedwell in her book Affective Relations: The Transnational Politics of Empathy,4 where she aims to interrupt the assumptions of affective commensurability, transparency, and truth that characterize empirical accounts of empathy in what she defines as the “neoliberal compassion economy,” remarking on the pivotal role played by temporal as well as geographical coordinates. Pedwell is interested in unpacking and sabotaging a model of empathy that is rooted in colonial time, and according to which “the act of ‘choosing’” to extend empathy can itself be a way to assert power.”5 This model conveys at the same time the disproportion between individuals involved in the process and the deceitful conception of simultaneity and attunement as the neutralization of conflict. The first of these is based on social and geopolitical hierarchies between “empathizers” and “sufferers”—in some cases empathy even contributes to maintaining these structures of power. The most significant example is the entrenched conviction that affective capacities of privileged (middle-class, white, and/or Western) subjects can be cultivated through empathy, while the less privileged (poor, non-white, and/or “third world”) “other” are deemed to be the object of empathy. By investigating empathy through the lens of a socioeconomic transnational perspective, Pedwell is chiefly interested in unveiling how neoliberal market strategies incorporate and exploit the empathy rhetoric. Pedwell suggests reinhabiting empathy as a conflictual, ongoing, negotiation in order to resist the neoliberal myth of self-responsibility, according to which caring and empathizing are not only “the right thing to do” but “empathy, as an emotional competency, has become part of being a self-managing and self-enterprising individual.”6 Hence, it has become an “affective” skill to increase competitiveness and the accumulation of profit. In his documentary film from 1997, The Interview, Harun Farocki captured the gestures and languages of “emotional labor” by silently observing and filming over the course of three months in a training school for jobseekers. “Creativity” and “spontaneity” are the basic requirements for success that the tutors obsessively emphasize. To a candidate who has proved to be too rigid and serious, the instructor will advise: “a little spontaneity, a touch of sincerity, would not go amiss.” Clearly the student’s instruction is to simulate two attitudes that normally attest to and manifest an individual’s authenticity. And later, commenting on the performance of an older and more insecure candidate: “You should appear serious, but with joy and optimism.” Indeed, while the capital-optimizing model implies the myth of independence and self-assurance, certain weaknesses—especially when faked—are necessary for the construction and maintenance of hierarchies. When during a mock interview a young woman states that she has no weaknesses, the examiner is gravely disappointed. On the contrary, she compliments another candidate when she includes in her list of flaws an overly marked predisposition to autonomy and having the freedom to take the initiative.

Harun Farocki, The Interview, 1997. Source: Harun Farocki GbR.

Harun Farocki, The Interview, 1997. Source: Harun Farocki GbR.

It was through Farocki’s work that, some years ago, I started delving into the intricate entanglement between empathy and authenticity, ironically through the work of a filmmaker who seems to not explicitly engage with this mechanism.7 But, in fact, empathy is such a crucial question in Farocki’s cinema that it is embedded in its method, as he states in a short yet inspiring text, “Einfühlung,” written in 2008 for the publication Applied Theatre Lexicon After Gustav Freytag.8 Instead of merely abandoning a word that has been exploited by the economic, political, and cultural system to invent a new, “uncorrupted” term, Farocki invites us to reconnote it: “Empathy is too good a word to leave to any other side” and it is “a finer expression than ‘identification.’” By claiming that “It should be possible to empathize in a such a way that it produces an effect of alienation,” Farocki advocates for pushing the boundaries of empathy to the point where one cannot any longer be comfortable with their own previous experience and conception of it. Rather than rejecting this problematic term, Farocki’s goal is to recharge empathy’s value and meaning.

Diaz highlights one more aspect that Hartman has thoroughly analyzed in both Scenes of Subjection and Venus in two Acts and that was pivotal for Farocki’s early works.

Thinking about that comment on the Washington Post story, there may be something about empathy, in the adamantly gestural smoothening of otherwise clashing interests, that resembles how liberal democracy short-circuits its convoluted system of complicities via a denial of the violent payoffs that make it an untenable system in the first place, or how its operation frequently relies on ‘moral’ but often depoliticized language: freedom, respect, democracy; how, for all the nod toward recognizing the suffering of others, empathy can result in a kind of paralysis that achieves little but is protected by claims of good intentions and thus can be used to shield the status quo.9

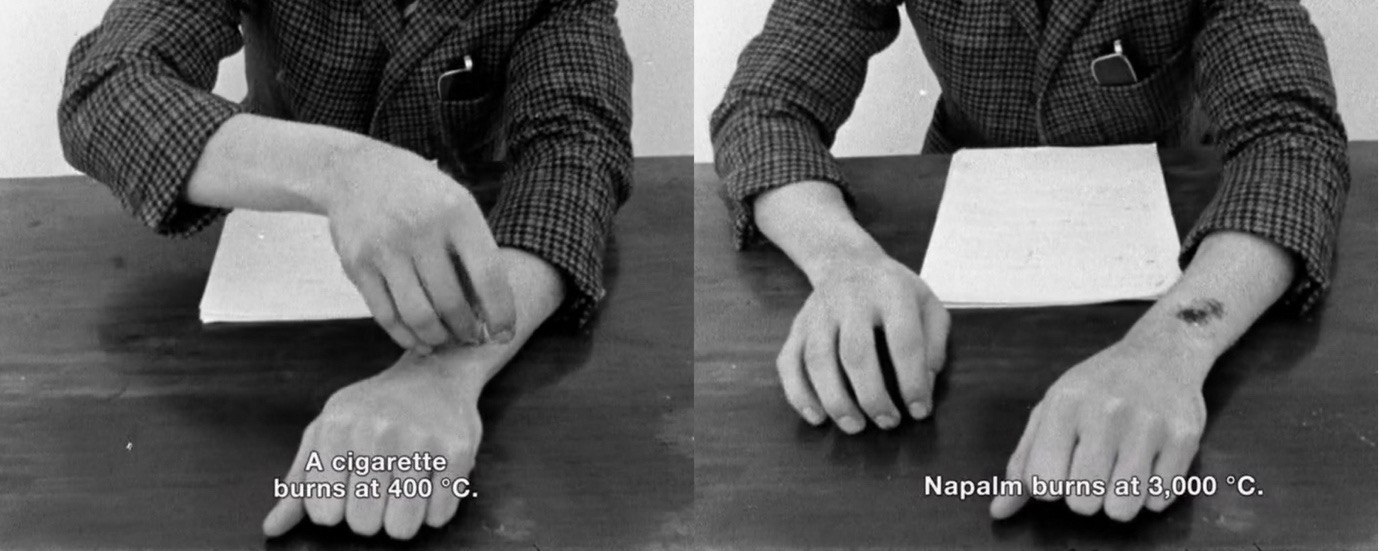

Harun Farocki, Inextinguishable Fire, 1969. Source: Harun Farocki GbR“Paralysis” is a key word in one of Farocki’s first films, Inextinguishable Fire (1969), about which much has been written. In the late 1960s, the issue of the overexposure of violence in film and media was already being widely debated, and Farocki felt an urgency to contribute to this discourse by asking, how can cruel images of the war in Vietnam circulate not just in order to shock the audience, but to stimulate political responses? By exposing his arm and burning it with a cigarette, in place of the crude footage of the bodies of Vietnamese victims charred by Napalm, Farocki metaphorically creates distance, a distance that allows him to counter the false media pathos that only superficially plays solidarity with the victim. Metaphor, here, is not an attempt to intellectualize or keep the real at arm’s length, but a way to reveal without simplification the grid of hierarchies that exists between power and language. A form of reactivation of meaning that makes visible what is unimaginable, by attempting to preserve the component that perturbs, in a way that defuses any automatic reactions.

Harun Farocki, Inextinguishable Fire, 1969. Source: Harun Farocki GbR“Paralysis” is a key word in one of Farocki’s first films, Inextinguishable Fire (1969), about which much has been written. In the late 1960s, the issue of the overexposure of violence in film and media was already being widely debated, and Farocki felt an urgency to contribute to this discourse by asking, how can cruel images of the war in Vietnam circulate not just in order to shock the audience, but to stimulate political responses? By exposing his arm and burning it with a cigarette, in place of the crude footage of the bodies of Vietnamese victims charred by Napalm, Farocki metaphorically creates distance, a distance that allows him to counter the false media pathos that only superficially plays solidarity with the victim. Metaphor, here, is not an attempt to intellectualize or keep the real at arm’s length, but a way to reveal without simplification the grid of hierarchies that exists between power and language. A form of reactivation of meaning that makes visible what is unimaginable, by attempting to preserve the component that perturbs, in a way that defuses any automatic reactions.

In a conversation between Hito Steyerl and Farocki in 2011, there is, in this respect, a compelling passage in which Steyerl sheds light on the analogy between documentary filmmaking and forensic techniques.

It is interesting that you should mention forensics, because it seems to me that there are strong similarities between forensics and documentary filmmaking, not just because both involve a science of trying to read objects, decoding their language and giving voice to things, but also because the very word ‘forensics’ is derived from ‘forum speech’—something I recently learnt from Eyal Weizman—which is the particular kind of rhetoric used by people speaking in a forum. On the one hand, forensics is all about the objects themselves and reading for patterns in order to reconstruct events, but on the other hand, there is a strong link to rhetoric, a rhetoric used to make the objects’ voices heard in public, but also to speak on behalf of them. The forensic scientist is, in a manner of speaking, a kind of ventriloquist.10

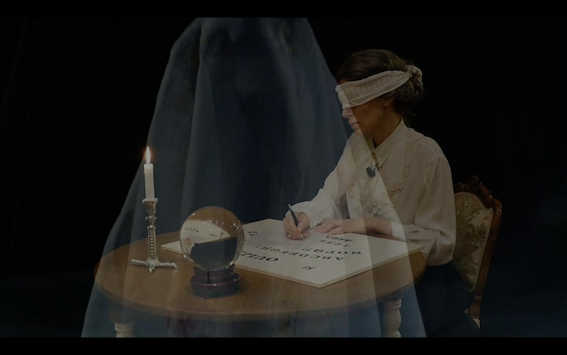

I want to pick up here again, where Farocki suggests finishing their long and rich conversation—“Perhaps that’s a wonderful place to end.” Ventriloquism, traces, silent objects to be reactivated, subjects to rescue from the past. From the forensic techniques inspiring documentary filmmaking to a more “occult” art practice which profoundly and ironically interrogates the nature of empathy and authenticity: Italian performance artist Chiara Fumai, whose work of giving voice to and channeling angry and silenced women across the centuries, offers a provocative empathic approach which plays with and sabotages the very idea of coinciding with the others. Fumai is, moreover, a generative case with which to think further Diaz’s proposition to explore the imaginative power of empathy and try to contrast its ambiguous assimilation within the neoliberal labor market, where this concept promotes the expression of the “right emotion at the right time.” Fumai developed an extraordinary reenactment practice to stage the wrong emotions at the wrong time, out of sync, after time. In her performances, she embodies several women who had too quietly or too violently inhabited history.

It is we who go. We unwork without a break, we plan everything in detail, we spend hours putting on disguises, we are as tireless as elves. We are madwomen. If only we were! We have simply chosen deculturalization as a mode of action. That’s why we are never the same woman. We would like to compose an alphabet that cannibalizes language through its margins, it’s S.C.U.M. dregs, which are also its limits. We come spoken (parlatA) to live this experience completely.11

To “come spoken” contains both a passive and active aspect to be traversed by the words and gestures of, among others: the late nineteenth-century controversial Italian spiritualist Eusapia Palladino; Zalumma Agra exploited as a Circassian beauty; Annie Jones known as the “bearded woman” circus attraction; Nicolosia Mantegna, wife and model of the Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna; Italian feminist Carla Lonzi; Valerie Solanas; and and German left-wing radical Ulrike Meinhof. In her performances, Fumai dresses up and talks like her characters, putting them in dialogue as in for instance the performance where “they” all read Solana’s SCUM Manifesto. As Giovanna Zapperi notes, feminist ventriloquism for Fumai is a way to redefine the “I” and the “we,” taking inspiration from the process of “deculturalization” developed by Lonzi in the early 1970s.12

Chiara Fumai, The Book of Evil Spirits, 2015.

Chiara Fumai, The Book of Evil Spirits, 2015.

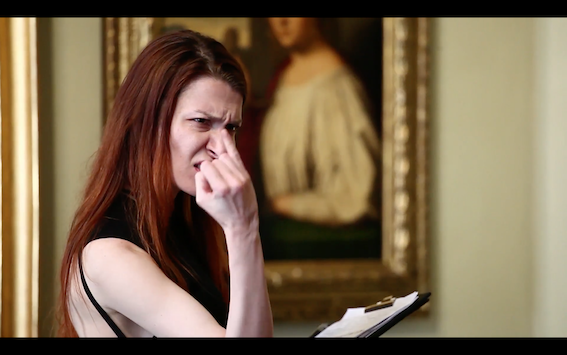

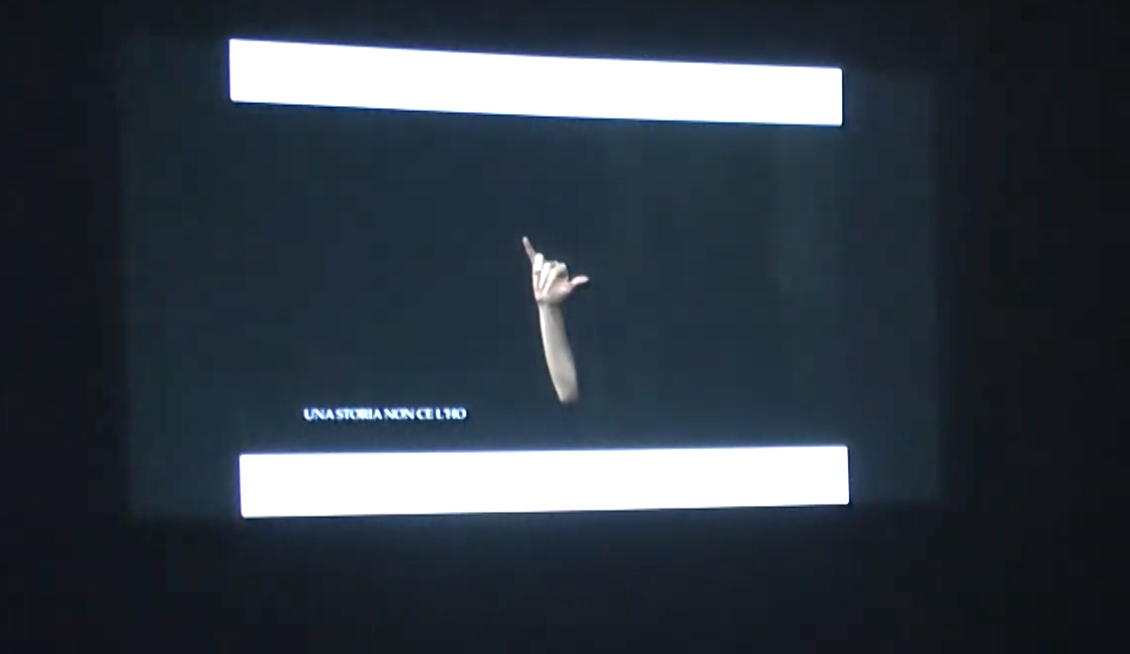

Feminist activism, however, is always combined with magic ritual and occult symbolism, as in the performance Shut Up, Actually Talk, which took place at dOCUMENTA (13) as part of the project The Moral Exhibition House. This haunted house is pervaded by an audio recording of a reading of Lonzi’s Sputiamo su Hegel, in line with the technique of tape recording often used by the Italian feminist, for instance in Self-Portrait13 and in Vai Pure.14 The protagonist of this performance is the Circassian woman Zalumma Agra, representing a pure, pale beauty from the East, who was “exhibited” wearing afro wigs and forced to stay silent during the show to stress her strangeness. Zalumma was a slave before she became an “exotic attraction,” and it is only at the end of Fumai’s performance that she is finally able to speak through the words of Lonzi’s text from 1977, Io dico Io (I say I). In order to free herself from silence, paradoxically, she needs to pronounce the “I” of another woman—Lonzi—through the mouth of a third woman, Fumai. And hence the intersection between the three “I’s” is not a mere empty game of mirrors that dissolves itself, but rather one that forms a powerful polyphony. This is also at stake in the work I did not Say or Mean “Warning” (2013), a guided tour through the Querini Stampalia collection in Venice to present the Renaissance portraits painted of often anonymous women. The sparse information about their lives is abruptly interrupted by an encrypted message coming from the paintings themselves, which Fumai delivers in the International Sign Language. Visibly angry, she reenacts the words recorded on the answering machine of a feminist group affiliated with the Lotta Armata. This is the subtle line along which Fumai builds her sophisticated performances on the controversial relationship between violence, rage, and female identity; shows where she meticulously stages the identities of her characters—without completely surrendering to them—so, that is, not in the name of self-annihilation. These women ask to be heard, to be hosted bodily by Fumai, but everything needs to be perfectly prepared to enact these inauthentic, precise, unruly dialogues.

The mediation staged by Fumai, although played out on the level of a performance (or precisely because of its fictive dimension), adds a precious model for reflecting on the way we access others’ experiences: anger, silence, inability to react in a timely fashion. Fumai redeems her protagonists out of time, transforming delay into a necessity. Something touches us from the outside, and now this encounter affects us. Here, empathy is not merely the projection of personal needs, nor is it a set of procedures to follow in order to optimize relationships; it is a transformational turning point, which inevitably remolds rather than allow someone else’s true feelings and thoughts to be deciphered in an appropriate manner.

Chiara Fumai, I Did Not Say or Mean “Warning,” 2013.

Chiara Fumai, I Did Not Say or Mean “Warning,” 2013.

Video, uploaded to YouTube November 6, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RGYj_5HgN4.

Chiara Fumai, still from a lecture performance given by Fumai at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste.

Chiara Fumai, still from a lecture performance given by Fumai at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste.

Video, uploaded to YouTube Jan 24, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1O13kqPe2iU.

Clio Nicastro teaches Cultural and Critical Theory at Bard College Berlin and she is currently affiliated with ICI Berlin. She is the author of La Dialettica del Denkraum in Aby Warburg (Palermo University Press, 2022) as well as the co-editor with Cristina Baldacci and Arianna Sforzini of Over and Over and Over again. Reenactment Strategies in Contemporary Arts and Theory (ICI Berlin Press, 2022). Since 2022 she is a member of the board of directors of the Harun Farocki Institut.

Footnotes

1 Simon Baron-Cohen, Zero Degrees of Empathy: A New Theory of Human Cruelty and Kindness, London, 2011. 1

2 Paul Bloom, Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, New York, 2016. 2

3 Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Oxford, 1997. 3

4 Carolyn Pedwell, Affective Relations: The Transnational Politics of Empathy, London, 2014. 4

5 Carolyn Pedwell, Affective Relations, p. 95. 5

6 Carolyn Pedwell, Affective Relations, p. 54. 6

7 Harun Farocki: Empathy, an exhibition curated by Antje Ehmann and Carles Guerra, which took place at the Fundació Antoni Tàpies in 2016. 7

8 Harun Farocki, “Einfühlung,” in Hebbel am Ufer (ed.), 100 Jahre Hebbel Theater. Angewandtes Theaterlexikon nach Gustav Freytag, Berlin, 2008, pp. 21–22; English trans.: “Empathy,” in Antje Ehmann and Carles Guerra (eds), Harun Farocki. Another Kind of Empathy, Barcelona, 2016, pp. 104–05. 8

9 Glenn Diaz, “Empathy at the End of the World: Notes on Fiction and Resistance,” Rosa Mercedes 04 (August 2022), /en/2022/05/13/empathy-at-the-end-of-the-world-notes-on-fiction-and-res, accessed September 12, 2022. 9

10 Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl, Cahier#2: A Magical Imitation of Reality, edited by Joanna Fiduccia, Leamington Spa, 2011 [online], www.kaleidoscope-press.com. 10

11 Chiara Fumai’s quotation from Milovan Farronato, “The Disquieting Muses of Chiara Fumai: Between Truth and Lies,” in Andrea Bellini, et al. (eds), Poems I Will Never Release: Chiara Fumai 2007–2017. Critique d’art, Catalogues monographiques, Geneva, 2021, p. 26. 11

12 Giovanna Zapperi, “Living with Contradictions,” in Bellini, et al. (eds), Poems I Will Never Release, p. 35. 12

13 Carla Lonzi, Self-Portrait, Brussels/London, 2021. 13

14 Carla Lonzi and Pietro Consagra, Vai pure: dialogo con Pietro Consagra, Rome, 1980. See also the related project by Karolin Meunier, “A Commentary on Carla Lonzi’s Via Pure,” https://karolinmeunier.org/practice/lonzi/, accessed September 12, 2022. 14

September 15th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04