A Visual Sceptic: Thoughts on Harun Farocki’s Descriptive Criticism

Harun Farocki’s 1995 video installation Interface/Schnittstelle consists of two synchronized video-channels, one on the left and one on the right.

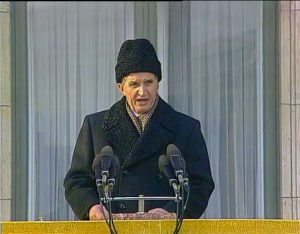

Initially, on the left-hand side, one can see someone writing in a notebook, and on the right, a TV in an apartment. On the TV screen, a crowd scene is followed by the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu giving a speech. A voice says, “I can hardly write a word these days if there isn’t a picture on the screen at the same time. Actually: on both screens.” After these words, the viewer becomes aware that the typist’s hand belongs to a man—Harun Farocki himself—sitting at a VHS film-editing table.

Farocki proclaims, “this is a work station, an editing station for the reworking of images and sound,” and then goes on to explain what’s in front of him: a control panel, a video player for playback and one for recording, and two monitors.

Farocki, watching the scene with Ceaușescu on one of the monitors, forms a square with his hands in front of the screen to frame the image. The clip, filmed on December 21, 1989 we are told, was filmed by Paul Cozighian off the television at home. Having seen live on-screen the state’s propaganda events interrupted by protesters, Cozighian had then turned his own camera toward the street. There, through the camera’s eye, he saw a large crowd of people leaving the staged tribute to Ceaușescu before the event had ended.

The clips, from one of Farocki’s earlier films, Videograms of a Revolution from 1992—made together with Andrei Uijca—covers five dramatic days in Romania in December 1989. A depiction of the popular uprising that led to the execution of Ceaușescu and the overthrow of the dictatorship he had maintained since 1967.

Videograms of a Revolution contains only previously filmed material: footage filmed during the dictatorship shown on state-controlled television, deleted scenes from BBC news reports, sequences filmed privately by people on VHS video cameras, and clips from the eventually stormed national television station (which would be used by the protesters to stage, among other things, a kind of live interrogation of those responsible for the authoritarian repression).

Interface, R: Harun Farocki, 1996 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Interface, R: Harun Farocki, 1996 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

In many ways, it feels natural to begin an essay on Harun Farocki with Interface/Schnittstelle. The installation is kind of an autobiography, an autofiction. Or rather, perhaps an associative reflection on how a body and mind that has worked with film for decades has shaped, but at the same time been shaped by, its material. The film’s framing situation shows Farocki, sitting at his editing table, looking at the films he has produced throughout his career.

From the mid-1990s, Farocki also began making video installations for art spaces, and soon his work was (and still is) shown in a wide range of solo and group exhibitions around the world. As Interface/Schnittstelle was the first installation Farocki made, it is therefore also something of a milestone in his production.

In the essay “Cross Influence / Soft Montage,” Farocki writes about why he decided to move towards an installation format in the mid-1990s—a decision born partly out of economic considerations: when Videograms of a Revolution premiered in 1992, there had been only one person in each of the two Berlin cinemas showing the film.1

But, what seems to have been more important was the conceptual reframing entailed by the change in the way people watch films in a gallery space compared to the space of the cinema. Later, in 2002, Farocki writes that those who visit “art spaces have a less narrow idea of how images and sound should conform. They are more ready to look for the measure of a work in the work itself.”2

In “Cross Influence / Soft Montage,” Farocki also explains in more detail what one is actually doing when placing two images beside each other, and the possibilities the method opens up. It’s about creating a relationship—not only between one image and the next that follows but also with the one that comes next to it. One image is juxtaposed with another in such a way that the meaning of each sequence must be constantly shifted towards a new context. This process of translation is at the heart of Farocki’s soft montage, which, unlike the classical montage’s attempt to shock and disrupt, seeks to achieve the comparative and relational creation of meaning.

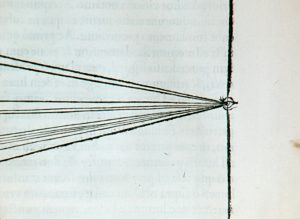

Following the images from Videograms of a Revolution, the clips used in Interface/Schnittstelle are taken from what is perhaps Farocki’s most famous film, Images of the World and the Inscription of War from 1988. A close-up of an eye being made-up is shown alongside an early model of a plotter machine in the process of drawing a window. Farocki says, “To date only words, or sometimes music, have comment on images. Here images comment on the image.”

Interface, R: Harun Farocki, 1996 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Interface, R: Harun Farocki, 1996 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

Images of the World opens with a strange scene: an industrial site with a kind of canal running through it; waves meeting an artificial sandy beach. A female narrator proclaims that the waves of the sea have the power to awaken the human imagination and to set the mind free. She then says that what sets thought in motion is put under a scientific microscope, in a wave simulator in Hanover. This kind of reflection on science’s, if you will, desire to map more and more of the human psyche serves as a kind of leitmotif in Images of the World.

The film discusses everything from the development of photogrammetric methods for measuring buildings (i.e. using photography and the principles of perspective to make mathematically correct descriptions of reality) to what it meant for women in Algeria to take off their veils and be photographed by the French policing powers. Machines that draw, measure, and simulate reality are also ever-present in the film. The images alternate with slightly hypnotic and fragmented background piano music. As a viewer, it is difficult to predict which thematic leap will happen next: which image will be juxtaposed with, say, a Lufthansa flight simulator, or a scene from a scene from a life drawing class. In other words, the film justifies being called an essay film, if by that we mean retaining its openness, and its ability to constantly establish new connections and expand its own thematic order.

Shortly after the wave sequence, the narrator utters: “Enlightenment, that is a word in the history of ideas, in German Aufklärung.” The phrase is repeated several times and given various additions—comments on the uses of the word Aufklärung—in different institutional contexts, for the police and military among others.

Even on a metaphorical level, Images of the World addresses the question of the Enlightenment. The film dwells largely on propositions of the visible and the invisible, or what it really means to see something. It reveals that seeing, and wanting to see, are activities tightly intertwined with a whole range of phenomena that, if not carefully examined, can be more obscuring than enlightening.

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

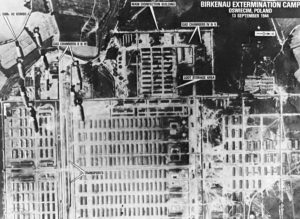

Perhaps the most sustaining aspect of Images of the World is the narrative surrounding the “discovery” of Auschwitz. It has been established that images of the Holocaust camps were there for the world to see as early as 1944 in aerial photographs accidentally taken by British military aircraft during a bombing raid.

However, it would not be until 1977, we are told, that what was then known about Auschwitz was linked to the photographs of 1944, when a review by the CIA of intelligence material from the Second World War discovered that the British military aircraft had captured Auschwitz on film. This might not seem so startling in itself, were it not for the fact that even at the time the photographs were taken, camp inmates, having managed to escape, had let the world know about the horrors of what was happening in Germany. Information that Britain and the Allies apparently did not care about—arguing that it was more important for them to win the war than to stop the industrial mass murder that was going on before their eyes.

I think Farocki ethical stance is clear in when he tells us about the history of the long invisibility of the Holocaust. An ethics that goes beyond the case at hand and can be formulated in a question: Just because there’s a photograph, does that mean that everything can be known about a particular person, thing, or event? Or to put the question another way: Why is it that the visible is constantly privileged as something truth-bearing in modernity when, in many cases, it provides very little, or in some cases virtually no information at all?

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

The British military was the first workplace to be made more efficient with the help of photographic cameras. Cameras were attached to bombers flying over Germany in the First World War to make it possible for pilots to see whether the bombs they’d just dropped had hit the target. The camera became a control tool that would make warfare more effective.

So that’s why there were pictures of the Holocaust camps in the first place. Images were produced, not for anyone to look at the object they were depicting, but to judge the effectiveness of RAF personnel’s practice. These images were produced in a closed system for a closed system. Farocki would come to call these types of images “operational images.”

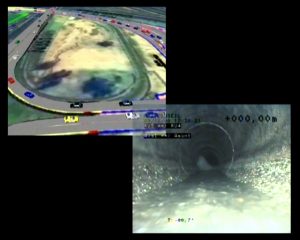

In his essay “Manual: Harun Farocki’s Instructional Work,” Volker Pantenburg commented on Farocki’s operational images in relation to another two-channel video installation from 2004, Counter-Music.3 Pantenburg describes how the installation’s perhaps most important metaphor is circulation, how the images without an author produce themselves and then spread, more or less automatically, into society. These images may feel familiar—they may be recognizable from the visual expressions of popular culture, but they may also evoke a sense of dystopia. A fear of a world where machines have taken control. But as Pantenburg points out, Farocki’s interest lies not in describing these two things, but rather in describing what these images do and what can be done with them.

What is “done” in the case of Counter-Music is the city of Lille itself. The film begins with surveillance sequences from a sleep laboratory, accompanied by footage of what appears to be an electrocardiogram (ECG). The film has no narration, using silent film-like black screens with white text instead. Soon, scenes from another film, Dziga Vertov’s 1929 classic The Man with the Movie Camera, are shown. A man wakes up and walks out of the portal of an apartment building with his camera over his shoulder. A car is waiting for him. He gets into the car and the vehicle drives away. He sets up his camera on a tripod to film the journey. The narrator in Counter-Music accompanying the clip states that “For Dziga Vertov, the day begins with the production of images,” and continues: “for us the day begins with their reproduction.”

Counter-Music, a film that mixes sequences from a wide variety of sources (including a system of cameras in sewers set up to detect faulty welds; public transport control systems; and footage from surveillance cameras) shows some similarities with The Man with the Movie Camera. Both films take place from dawn to dusk (a temporal framing that Farocki also used in the 1993 film A Day in the Life of a Consumer) and, in both, alongside the city, the cameras play the leading role. In Vertov’s case, however, it is people with their cameras who are depicted, whereas in Farocki’s film it is rather the cameras with their people. And unlike in Vertov’s classic, the images in Counter-Music, as mentioned, are not just something that describes a city—film and photography actually regulate daily life in Lille. Visual media regulates how lights are turned on and off and how traffic flows, and it also detects anomalies: people who stand still for too long are detected and scrutinized. A circulation of images that regulates the circulation of people.

Counter-Music, R: Harun Farocki, 2004 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Counter-Music, R: Harun Farocki, 2004 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

I have often wondered when looking at Farocki’s films whether they could be described as critical. On a banal level, of course, they are. Images of the World, for example, can be said to be critical, of modernity and of a blind faith in the camera as a truth-teller. But at the same time, the film is skeptical of the notion of an enlightened, critical subjectivity: it questions something in modern investigative man, the urge to reveal without realizing one’s own limitations. So perhaps the question is rather one of how Farocki goes beyond criticism in his films.

The very concept of criticism is impossible to define in just one way. The word was borrowed into Swedish from the French critique, which has its roots in the Latin criticus, which in turn comes from the Greek kritikē, which roughly means “the art of judgment” or “the ability to judge.” Most often the word is probably used, as the Swedish Academy’s dictionary says, to assess the value or the qualities of something or someone, and one can add, not infrequently in a negative sense—that is, to find faults and shortcomings. To be a critic and to write criticism about different artistic expressions is another thing that has its own specific history that is linked to the development of a market for opinions, which comes via the institutionalization of the public sphere in Europe in the late eighteenth century.

The ability to be critical has been described by the philosopher Michel Foucault in his essay “What is Enlightenment?” (1984) as a characteristic of modern man. Here, Foucault takes a reading of Immanuel Kant’s 1784 article of the same title, which purports to explain how the Enlightenment meant that people could free themselves from their predetermined authorities and instead use their intellect and rational thinking for guidance. Foucault, for his part, argues that the truly original aspect of Kant’s text was that it expressed the hope that from now on people would not only imagine progress and improvement, but also relate it critically to their own situation in life, their own society, and thus also open up the possibility of the enactment of an as-yet-unknown future.

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Images of the World and the Inscription of War, R: Harun Farocki, 1988 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

In other words, being critical can a mean engaging with an object in at least two different ways: identifying and describing a situation or phenomenon, and making a judgement or evaluation of someone or something. There has been a debate in the humanities, at least since the 2000s, about what a critical approach actually does for our understanding of the world, and many (including philosophers Bruno Latour and Rita Felski) have called for methods of reflection that are more devoted to description and deep analysis and less to a “hermeneutics of suspicion” (a term originally coined by philosopher Paul Ricœur to describe the philosophical ambitions of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud).

The literary scholar Toril Moi is one of those who has presented interesting thoughts on what to do if you want to be critical but not suspicious. In her book, The Revolution of the Ordinary: Literary Studies after Wittgenstein, Austin, and Cavell, she sets out to valorize description (which, according to Moi, has held a rather low status in academia in the past—having been accused of reproducing ideological notions rather than critically examining them) as a critical method. Moi argues that to describe something can be to admit one’s confusion about the world. To illustrate in detail what one is studying can create an awareness of one’s own limited capacity to understand.

Moi points out that the reader, when describing, is not necessarily saying that this text wants to mislead or misrepresent, but rather, that it is possible to read and understand this, but it will take a lot of work and I will never be fully able to understand all aspects of it. In other words, the problem is in us, not in the text itself: “Note the difference between assuming that the text is hiding something from us, and assuming that the problem is in me, in us.”4

*

I think one answer to the question of how Farocki exercises his criticism is that he engages in a descriptive activity that is close to how Moi defines it.5

One of the films that can be highlighted in this context, and which shows how the descriptive can be used in a critical manner, is Inextinguishable Fire from 1969. The film’s famous opening scene has a minimalist set design: Farocki sits at a table in front of the camera. His eyes fixed on a piece of typewritten paper, he reads a testimony provided by Thai Binh Dan to the International Tribunal for War Crimes in Stockholm in 1967, describing the effects of napalm during the Vietnam War. Farocki then looks straight into the camera and reflects on the impossibility of showing or describing for the spectator of film or television the devastating effects of napalm.

How can we show you napalm in action? And how can we show you the damage caused by napalm? If we show you pictures of napalm damage, you’ll close your eyes. First, you’ll close your eyes to the pictures; then you’ll close your eyes to the memory; then you’ll close your eyes to the facts; then you’ll close your eyes to the connections between them.

Interestingly enough, it is precisely the lack of a descriptive context that makes the viewer unwilling or unable to understand what it means to be burned by napalm.

In order to establish a relationship between the violence of the world, the self and the body, which viewers can understand, Farocki then takes a radical approach. He takes a cigarette and burns his own arm with it while a voice-over announces “A cigarette burns at 400 degrees. Napalm burns at 3,000 degrees.”

When the cigarette scene reappears in Interface/Schnittstelle, Farocki sits in front of his screens to recite the script of a 1960s film thirty-six years later—word for word, with some delay. He then says: “When he’s done speaking, the author burns himself, although only on a single point of skin. Even here, only a point of relation to the actual world.”

Farocki urges the viewer to be cautious about their reactions to what they see, and describes an event in a way that forces the viewer to question their own conclusions and knowledge. But something else happens in the scene as well: it is as if Farocki is trying—against better judgement—to capture what the film medium does not really allow to be depicted.

*

I think that anyone who wants to understand Farocki’s critical descriptiveness must consider the sense of lack and disappointment that it creates. A disappointment in the film industry’s ability, and perhaps ambition, to portray the world in all its horror. Also, a resignation to the ontological conditions of the medium of film. A question on the doorstep is whether filmmakers risk lulling people into a false sense of hope that now they will be able to “know what it’s like.” Because that, as Farocki has repeatedly illustrated not least in Images of the World, is largely how images have functioned in modernity.

Images of the World reflects very interestingly on the relationship between sight and other sensory impressions. Taste must be in contact with the world around it for any information to be tasted, and it differs in that way from sight, which can achieve information by maintaining its comfortable distance from what it observes. The question then is whether film can reproduce the impulses of the other sensory perceptions at all, or whether the filmmaker would do better to instead point out the impossibility of fully representing anything other than what is visible. Perhaps both can be achieved: in Interface/Schnittstelle we witness and understand the pain of putting a burning cigarette to the skin, but we are also made aware of the imagination’s deficiencies which can make it difficult for us to absorb such information.

In Interface/Schnittstelle, Farocki also points out, more than once, the difference between looking-and-thinking, and looking-doing-and-thinking. He experiences confusion and a sense of lack when he’s not at the editing table. Recall the opening words of the film, “I can hardly write a word these days if there isn’t a picture on the screen at the same time. Actually: on both screens,” and compare them to the statement, “Today I can barely think through a new film if I am not at the editing table. I write into the images and then read something out of them.”

The motto—you need to be a physical body in the world to better understand images—does not only apply to those who are used to producing films themselves, but to all of us. It must be like this since, as mentioned, images are not in all cases something that are made for us to look at. Film and images are often operational—part of systems that create “reality,” largely without our involvement. They produce information that we are not meant to look at, but which nevertheless constantly shape our lives.

Finally, the opportunities that do exist to represent the world through the medium of film are rarely fairly distributed. Perhaps more than any other film, Farocki’s Videograms of a Revolution illustrates this point while simultaneously showing how quickly the material conditions for filmmaking can shift. The scene in which Ceaușescu delivers his speech to the staged demonstration in support of the regime on December 21, 1989 is telling enough. The sudden camera shake. Someone shouting, “who is shooting? Someone is shooting,” and a man coming out to whisper in Ceaușescu’s ear, “They are entering the building,” before the broadcast is cut off.

A historic moment that marked not only the end of decades of dictatorship, but also of control over the image, and over the portrayal of reality through film. Soon, the state-controlled televising of the revolution would be challenged by the common man’s hand-held video camera.

Videograms of a Revolution, R: Harun Farocki, 1992 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

Videograms of a Revolution, R: Harun Farocki, 1992 ©Harun Farocki GbR, Berlin

*

At the end of Interface/Schnittstelle, Farocki—as if to enchant something—holds his hand over a book showing a picture of the mathematician Alan Turing and says: “Might this editing station be an encoder, or a decoder? Is it about decoding a secret, or keeping it?”

This enigmatic ending is symptomatic of the descriptive critique delivered by Farocki in film, and I think the answer to his question is that making film is about both revealing and keeping secrets, but so is, which it is important to note, any form of communication.

As described, Farocki teaches us how little we can actually see with our eyes, despite the ideals of enlightenment and the constant progress in the techniques of visualization in modernity. But I don’t think that this lesson is one that leaves us in communicative despair—rather, it reminds us that to see is only one form of interaction with the world along with countless others.

Farocki’s films definitely evoke—or maybe “translate” is a better word—other sensory experiences into the visual. But they also address the fact that this gesture of translation is partly an act in vain—with other words they describe their own shortcomings. Or maybe, in fact, what they address is our shortcomings as viewers, evoking something closer to the humbling experience as described by Toril Moi, that our understanding will always be limited.

Film (to be compared with other visual medias such as geometric perspective and photogrammetric methods) is a descriptive technique that can help us understand things, but it’s also a technique that can only gain from being accompanied by other means of achieving information. To see is one thing, to feel is another, to listen a third, to make (for example film) a fourth, and so on. And I would argue that Farocki’s work encourages anyone wanting to better understand the world to develop as many of these descriptive techniques as possible.

Hans Carlsson is an artist, curator and writer living in Malmö and in Berlin. He was a guest of the Harun Farocki Residency in winter 2021/22, realized with the support of IASPIS, Sweden. Hans Carlsson’s artistic and curatorial practice often revolves around issues such as the history of labour, the antagonism between global progressive socialism and national social democracy and the individuating consequences of institutionalization in western modernity. Topics which are understood as deeply entangled with the history of cinema, art and literature – and lately in Carlsson’s practice also put in relation to mythological thinking and the intellectual heritage of Greek antiquity. https://hanscarlsson.com/

Footnotes

1 Volker Pantenburg has pointed out that an often-described regular transition—from one cultural economy to another—is exaggerated; Farocki continued to make conventional film and television even after he showed his first video installation. Volker Pantenburg, “Manual: Harun Farocki’s Instructional Work,” in Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (eds), Harun Farocki Against What? Against Whom?. London: Koenig Books, 2009, p. 95; and Hans Carlsson in a conversation with the author. 1

2 Harun Farocki “Cross Influence / Soft Montage,” in Harun Farocki Against What? Against Whom?, p. 73. I find this reflection by Farocki interesting, even though, as Volker Panterburg commented after having read a previous version of this essay, one should be careful about drawing any “transhistorical conclusion” from Farocki’s 2002 text, which might be more of an “(optimistic) diagnosis of the constellation in the early 00s.” Hans Carlsson in an email conversation with Volker Pantenburg.2

3 Volker Pantenburg, “Manual: Harun Farocki’s Instructional Work,” pp. 93–100.3

4 Toril Moi, Revolution of the Ordinary: Literary Studies After Wittgenstein, Austin, and Cavell. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017, p. 181.4

5 Several authors have had similar thoughts: Volker Pantenburg uses the word “instructive” to encapsulate the pedagogical and explanatory approach of Farocki’s work. Pantenburg does this partly for etymological reasons, since the word instructive contains the suffix structure, which becomes important in this context to explain how Farocki was not alone in this; much of twentieth-century philosophy was similarly preoccupied with describing how structures in particular “configure, mould and shape narration, meaning and ideology.” See Volker Pantenburg, “Manual: Harun Farocki’s Instructional Work,” p. 94.

In this context, the essay by Antje Ehmann (curator, writer, and artist, who collaborated with Farocki on several projects including Labour in a Single shot), “Working with Harun Farocki’s Work,” is also worthy of mention. The text discusses the extent to which Farocki can be said to be working with an empathetic method. The author herself is surprised that the term can capture anything in Farocki’s films: the word empathy signals a kind of closeness to the subject that borders on emotional involvement, something Farocki actively worked against throughout his career. On the other hand, Ehmann writes that there is something empathetic in Farocki’s attempt to engage with the world in his desire to understand it. A kind of patience and openness to what is being investigated and filmed that also characterized the filmmaker’s ability to return to the same subject time and again, to constantly reassess his thoughts and find new and more angles. See Antje Ehmann, “Working with Harun Farocki’s Work,” in Antje Ehmann and Charles Guerra (eds), Harun Farocki: Another Kind of Empathy. Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 2016.5

The essay was first published in Swedish in Point of View/POV.

Translation into English: Hans Carlsson

Proofreading: Amanda Gomez

July 19th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 06