Retraditionalization in Decolonization: The Indigenous Indonesian Manager

Following Dutch acknowledgement of Indonesia’s independence in 1949, a period of parliamentary democracy in Indonesia, spanning the majority of the 1950s, was faced with political instability and significant struggles related to the government’s role in development. Throughout the 1950s, seven prime ministers came and went, as confidence in democracy declined. In 1957, President Sukarno declared martial law and a transition to the so-called “Guided Democracy” of the period between 1957 and 1965, in which various aspects of Indonesian state-society relations were revamped to make way for a new, revolutionary society. President Sukarno envisioned a society managed by revolutionized state apparatuses, the administrators of which weren’t merely managers but also revolutionaries.

Discussions around the development and creation of effective cadres of modernizations had been highly hegemonic during the 1950s, with the United States and their aid network maintaining a dominant position in pushing forward ideas of modernity.1 They prescribed that traditional societies like Indonesia were to be modernized through the development of “cadre of modernizers”—that is, managers working above their historical and local embeddedness—who would allow for the gradual change from traditional to modern societies. Modern society, as explained by Abraham Maslow, was imagined as a liberal, industrial society based on the example of the ideal—the United States.2 This drive toward modernization was also shared by the communist camp, although they saw the reverse—the state as the progenitor for societal change within the post-class communist dream. The development of the social sciences, in particular scientific management, public administration, business administration, et cetera, was predicated on this modernist belief in the formation of a brand new, highly modernist society, cut off from its historical roots. As the American sociologist Edward Shill noted in the mid-1950s, ideology had ended, and what was left was for the so-called “moderns” to solve the technical problem of creating modern societies.3

Bringing together both American and Soviet ideas about modernization, President Sukarno saw himself as head of an Indonesian modern renaissance, whilst also viewing the state as the perfect vehicle to bring about the necessary changes in Indonesian society. However, differing fundamentally from the modernist visions of both the US and the post-Stalin Soviet Union—both arguably being somewhat anti-revolutionary in favor of glorifying the position of the so-called “experts,” including those of expert managers—Sukarno saw the process of modernization itself as inherently revolutionary and wanted the integration of Indonesian society within the state to be led by revolutionary politicians and leaders. Thus, his Guided Revolution was both an Indonesian and a global revolution from the non-Western periphery.

This revolution would restructure and retool the Indonesian nation, creating in the process the ideal “new Indonesian man.” In a public meeting held in Medan in 1962, Sukarno stated: “Our revolution is a cultural revolution, a historical revolution, a national revolution, a military revolution, yes a revolution ‘to create a new Indonesian man.’”4 While this notion of the re-creation of the individual has its roots in both liberal and Marxist political ideology, a tension also exists between this ahistorical drawing of the new Indonesian man and the practical realities of the problems of Indonesian managerialism.

The Problem of Indonesian Culture

In an article entitled “The Crisis in the Indonesian Culture” published in 1955, the Indonesian public intellectual Soedjatmoko noted that the issue with Indonesian development was “clearly a crisis of leadership […]. Herein lies the failure of the old leadership which has guided us to the gateway of independence but is unable to disengage from the viewpoint which brought the first phase to a successful end and cannot adjust itself to the demands of the second.”5 This assessment was shared by American management specialists working in Indonesia at the time who were helping to build Indonesian managerial and administrative capacities. Cornell University management specialists were sent to Indonesia by American aid organizations to help the country develop education in scientific administration—in particular at the burgeoning Lembaga Administrasi Negara (State Administration Institute, henceforth LAN), formed in 1958. Joseph M. Waldman, who at the time was helping LAN, noted that “Mr Mintorogo [deputy director] and others are very reluctant to make those decisions which involve the fact that they have to face up to someone and say ‘no,’ or administer correction, or deprive them of what they want to do.” He also noted that “Indonesian officials display a touchiness about prerogatives, prestige, self-esteem that is a hyper-reaction against the former authority of foreigners, heightened by a frequent sense of insecurity arising from feelings of personal inadequacy for the jobs held.”6

The problem with the postcolonial Indonesian state was clearly more fundamental than merely being fixable by the construction of a “new Indonesian man.” Instead, it went to the core of state power itself—the inability to develop authority within the state administration. This meant that the state was unable to fulfil its function and project power beyond the capital or regional capitals. That the Indonesians were incapable of ruling themselves as a result of the venality and technical limitation of the Indonesian administrators—a long-standing colonial trope used by the Dutch to justify their continued control of the island— was defined as a cultural issue. That is, within this image, technical limitation is connected with cultural limitation. The primary objectives of the governments of the early- to mid-1950s were, thus, to concentrate capabilities in particular state apparatuses that would contain highly capable technical individuals.

Despite this, as Sukarno declared martial law in 1957 and Dutch-owned enterprises were nationalized, with the remaining Dutch nationals being kicked out of the country, these cultural and technical problems manifested themselves on a massive scale. Sukarno’s revolution was therefore intertwined with the managerial questions of the state, and the Guided Democracy itself became, in a way, a managerial revolution. Looking at the dozens of Indonesians sent abroad to study management science in the US during this period, we get a glimpse of the elitist vision of Indonesian state-society relations that would replace that of the new Indonesian man in the later context of Suharto’s New Order regime (1966–98).7 Instead of the ahistorical vision of the new Indonesian man, what is surprising about the developmentalist model of the New Order regime that appeared within the minds of new, US-educated Indonesian managers was its near-colonial nature. Yet, its appeal to Indonesian people was the promise that modernization theory would de-Europeanize administration by making it “American.” So, as a result, despite being in dialogue with the colonial-modernist project and its ideologies, the Indonesian managers could claim a decolonized position.

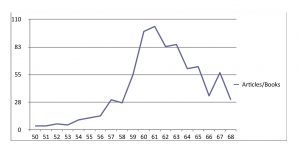

Picture 2: All book titles on scientific management and public administration published in Indonesia between 1950–68, showing increasing interest during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Fakih (2020).

The Appeal to Traditionalism

This continuation of the colonial developmentalist project can be seen in the way in which students of scientific management began to construct the functional relations of Indonesian society during their studies in America in the 1960s. Soegito Reksodihardjo, who had finished his dissertation under the management specialist Harold Koontz at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1962—titled “Skills Investment in a Developing Country: An Appraisal of Management Development for Indonesia”—said the following about Indonesian society:

“With the increase in the general level of education it is to be expected that rationality will gain in importance among the broader stratum of ‘the common people’. When such is the case, it will also be less difficult to make them aware of the importance of such terms as ‘effectiveness’ and ‘efficiency’, and a ‘rational’ or ‘business-like’ attitude can be eventually mastered. As long as the average educational levels are very low, emotional, traditional and/or social views are more dominant, and although not impossible, it nevertheless will require considerably more effort to implement a rational or systematic idea.”8

In this dissertation, he defined traditionalism as an end-spectrum that was in opposition to the modernist values of efficiency and rationality. He also defined modernity and traditionalism within a spectrum of education. The more educated one is, the less traditional and more modern one becomes. It would therefore pose a problem if the entirety of the national project were to be left in the hands of the traditional masses:

“If the economy were left to the masses, the result would probably be that either the subsistence level would persist or that the economy would collapse quickly. First of all, the very low level of education does not permit the people to know much about other needs beside those which are very basic, and with which they are already familiar by tradition. Second, even if they are fully aware of their wants, it is still a question whether or not they can do much to alleviate the shortcomings, since the general low level of income does not allow any significant capital accumulation. Third, even the small proportion of the middle class cannot be entrusted with the task of becoming agents for progress.”9

Thus, in Reksodihardjo’s construction, not even the middle class were to be trusted as agents of modernity. The masses were to be controlled, and true leadership was to be entrusted to the experts. This generalized and stereotypical view of the masses was widely shared by many of Indonesia’s expert elites that would find power in the New Order regime. This notion, that the people would flounder because they are unable to develop, is a colonial notion that was shared by colonial economists like J. H. Boeke. But Reksodihardjo tried to differentiate his position from Boeke by positioning a ladder of rationality and modernity, one which would allow the elites to guide the masses.

Also expounding on the dangerous position of the masses—but instead finding within it a certain potential—another Indonesian management student, M. Widoyoko Notoatmodo, studied the practice of gotong royong (communal participation in public projects in the spirit of community cooperation). Notoatmodjo’s dissertation—titled “Gotong Rojong in Indonesian Administration, a Concept of Human Relations,” defended at Indiana University in 1962—sought to understand how the traditional value of gotong rojong could be applied to solve Indonesia’s managerial woes. Notoatmodjo’s discussed three case studies in order to analyze the situations in which gotong rojong was used effectively. He found several factors which determined the effectiveness of gotong rojong: environmental background, that is, whether someone was from a rural, semi-urban, or urban background; togetherness, that is, the communality of the person’s environment, cultural background, education, profession, or social status; their understanding of gotong rojong; the degree of practice of gotong rojong; the degree of rationality, that is, whether a person is more inclined to be emotional or rational or both; and the tendency for collectivism.10

Like Reksodihardjos, Notoatmodjo focused mainly on the division between traditional and modern cultural traits. He explained gotong rojong as “a social institution [that] has been known and practiced throughout Indonesia for more than four thousand years, from the time of the population immigration from the mainland of Asia [in] about 2000 BC.”11 However, its effective application in the modern period was reliant on whether the individual had been Westernized. Notoatmodjo continued: “The domain of gotong rojong is any original and untouched village community in Indonesia, the kind of village community in which traditional Adat (customary) law is a guiding principle for every member of the community, and where Western influence has not yet been felt in the way of life of the members of that community.”12 He believed that gotong rojong could only work among those who had not been tainted by the competitive spirit of Westerners, the individualist tendencies of which would lead to the disintegration of its efficacy. Notoatmodjo saw the application of gotong rojong as a compromise to modernity. Instead of implementing full Westernization, the elites of Indonesia wanted to maintain a modernized Indonesian culture. Thus, the modern idea of gotong rojong was, according to Notoatmodjo, a new creation of Indonesian intellectuals who had enjoyed a Western education and training.13 This re-creation of Indonesian society was conducted through the invasive managerial strategies of retooling— eliminating segments of people within the administration that were deemed unfit. Within this context, the application of gotong rojong took on a totalitarian quality.

The modern reinterpretation of gotong rojong was shaped through the reinterpretation of ancient values.14 Instead of individualism and competition, the new Indonesian man was to work within a highly corporatist social system. The idea of gotong rojong in development was thus seen as a panacea through which to control the masses under the experts. This bifurcated image of the managers as both rational agents and suffering from a damaged culture is important in understanding how the managerial ideology developed in Indonesia. It is not merely interested in efficiency—that may not even be its main goal. The goal was to imbue the new elite class with a modicum of legitimacy as rational, modernizing agents amidst a sea of irrational, but soon to be rational, Indonesian peasants.

The Manager and the Developmental State

Discussions of Suharto’s Developmental State often focus on the Adat-based notions of the familial or integral state and its colonial roots. David Bourchier, for example, has pointed out the German root of the legal ideas which affected the development of Adat legalism,15 being that it is based on the idea that the law is an expression of the historical journey of a society. This rather conservative idea of the law seems anathema to the universalist notion of the new Indonesian man and the modernity that sprang forth simultaneously under the Guided Democracy, yet scientific management in its Indonesian incarnation would integrate these conservative notions and develop a local and Indonesian form of the developmental state that instead enshrined the notion of the dangers of the masses and positioned the experts on a pedestal.

That the rise of the managerial class originally occurred within the context of Sukarno’s revolution, which was an effort by the President to center the position of political revolutionaries, is highly ironic. The rise of the managers is also ironic in that it strengthened the traditionalist structure of Indonesian society by redefining the masses, from being a politically charged entity that could transform into the imagined new Indonesian man, into a dispersed, docile “floating mass” that reinforced the capitalist labor relations that had emerged during the colonial period. These developments point to the continuing part played by global forces in determining modalities between managers/administrators and the commoner in Indonesia during the period. It also highlights the failure of Sukarno’s revolution to redefine the Indonesian masses as agents of modernity. Instead, the traditionalization of Indonesian managers was seen to be the primary aim in order to reinforce the authority of the new managers, thus ironically indigenizing the managerial class.

During the New Order period, the shift from the state-centered developmentalist model of Sukarno’s Guided Democracy towards incorporating neoliberal tendencies also shifted the meaning of the managers. It reduced the position of managers from purveyors of state modernization projects to being the progenitors of more individualized projects. Yet, despite this, the legacy of the mid-twentieth century ideology of scientific management and the modality of the manager represented one of the most significant aspects of Indonesian decolonization. By combining traditionalist values, managerialism, and in conjunction with a military dictatorship, Suharto ensured systematization and a rationalization of violence against the masses, implementing an effective, and at times ruthless, authoritarian administration that nonetheless achieved some success in the terms of the neoliberal world order. For this, the position within the rational pole of the ordinary people of Indonesia had to be maintained at a level that would ensure compliance and obedience for the good of the nation-state, but which effectively foreclosed any revolutionary hopes or images relating to the new Indonesian man.16

Farabi Fakih is a lecturer and Head of the Masters Program at the History Department, Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He has conducted research on a variety of topics covering Indonesian urban history, knowledge decolonization and the history of corruption in Indonesia. He defended his PhD thesis at the History Department in Leiden University on the topic of decolonization and managerialism in the formation of authoritarian state and modernization. He has recently published the book Authoritarian Modernization in Indonesia’s Early Independence Period by Brill in 2020. It looks into the ways ideologies of managerialism are co-opted by the Indonesian elite in order to position their authority in the newly postcolonial Indonesian state. He is currently doing research on postcolonial Dutch-Indonesian relations and anti-corruption norm-settings during the New Order period.

Footnotes

1 See, for example, Michael E. Latham, The Right Kind of Revolution, Ithaca, NY, 2011; Nils Gilman, Mandarins of the future: Modernization theory in Cold War America, Baltimore, 2003; Nick Cullather, “Development doctrine and modernization theory,” in Alexander DeConde et al. (eds), Encyclopedia of American foreign policy, vol. 1, New York, 2002, pp. 477–91. 1

2 Bill Cooke, Albert Mills, and Elizabeth Kelley, “Management Theory in a Cold War Context: The Case of Abraham Maslow,” paper presented at “Cold War and Management: 3rd International Conference on Critical Management Studies,” Lancaster, July 2003, pp. 7–9 (January 3, 2003), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255634511_55, accessed June 4, 2022. 2

3 See Edward A. Shils, “The end of ideology?” (1955), in Chaim Waxman (ed.), The end of ideology debate, New York, 1968, pp. 49–63. 3

4 R. M. Soeparto, “Djiwa Pahlawan,” Bulletin Lembaga Administrasi Negara, vol. 9 (1962), p. 9. 4

5 Soedjatmoko, “De crisis in de Indonesische cultuur,” De Nieuwe Stem, vol. 10 (1955), pp. 328–29. 5

6 “Foreign Technical Assistance in Economic Development in a Newly Independent Country,” p. 78. 6

7 See Farabi Fakih, “Expertise and National Planning,” in Fakih, Authoritarian Modernization in Indonesia’s Early Independence Period: The Foundation of the New Order State (1950–1965), Leiden, 2020, pp. 87–130. 7

8 Soegito Reksodihardjo, “Skills Investment in a Developing Country: An Appraisal of Management Development for Indonesia”, PhD diss. University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), 1962, y pp. 154–55. 8

9 Ibid., p. 216. 9

10 M. Widoyoko Notoatmodjo, “Gotong Rojong in Indonesian Administration, a Concept of Human Relations,” PhD diss. Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, 1962, p. 196. 10

11 Ibid., p. 205. 11

12 Ibid., pp. 205–06. 12

13 Ibid., p. 218. 13

14 In fact, recent research has pointed to its creation dating to around the mid-1950s, when Javanese farmers themselves first heard the term. John R. Bowen, “On the Political Construction of Tradition: Gotong Royong in Indonesia,” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 45, no. 3 (May 1986), pp. 545–61. 14

15 David Bourchier, Illiberal Democracy in Indonesia: The Ideology of the Family State, London, 2014. 15

16 See Farabi Fakih, “The Military Expansion into the State,” in Fakih, Authoritarian Modernization in Indonesia’s Early Independence Period, pp. 50–86. 16

June 20th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04