The Angry Christ (Plot and Plantation)

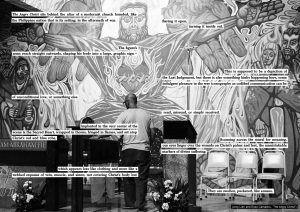

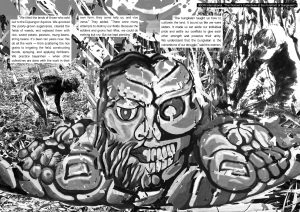

The Angry Christ (1950) is an unusual church mural located on the agricultural island of Negros in the Philippines. Situated within the compound of an industrial sugar mill, the mural’s flamboyant avantgarde sensibility cuts like a knife through the rural environment. For several years now, we have been unpacking the visceral sense of fissure, of puncturing, that this artwork produces, because it seems to us to embody a kind of queer logic that is not only disruptive but also generative, laced with a certain potential. This initial seed of recognition has since sprouted multiple interwoven tendrils of inquiry, which have together guided our ongoing study of The Angry Christ.

The mural’s creator, Alfonso Ossorio, was a Filipino-American painter who, despite being a visionary artist who was intimately connected to canonical figures like Jackson Pollock and Jean Dubuffet, remains relatively obscure today. We can speculate that certain particularities of Ossorio’s person and practice prevented him from being written into the dominant narratives of Western avant-garde art of the time: his commitment to religiosity, his hybrid ethnicity, the fact that he was indeed queer (“h.s. or b.s.,” as he wrote in one of his notebooks). But it would be wrong to entirely ascribe his lack of recognition to a lack of social privilege, because Ossorio also belonged to the ruling class. It was his family’s money that enabled him to leave the Philippines as a young child, acquire US citizenship and a Harvard degree, and gain a solid footing in the cosmopolitan art scenes of New York and Paris (as both an artist and a collector).

The source of all of this wealth was sugar: Ossorio’s family owned and operated one of the largest sugar milling companies in the Philippines, and it was for the worker’s chapel of this company that he was commissioned to paint his Angry Christ mural. Sugar—grown and processed in a country that had only just been granted nominal “independence” from US colonial rule after the end of the Second World War—could therefore be thought of as a kind of substratum to Ossorio’s life and work, the material base of his artistic practice. With this in mind, we knew that we wanted to look at Ossorio’s mural in relation to the sugar ecology in which it was embedded and to think of it as an active agent within this ecology. We wanted to ground our study of the mural in the sugarcane plantation.

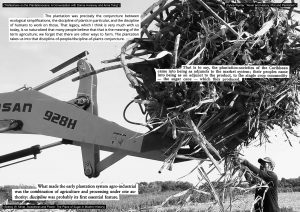

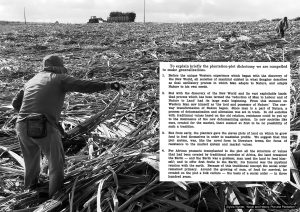

To delve into the plantation society of Negros—an island known as the “sugar bowl of the Philippines,” producing over half of the country’s sugar output—is to confront a reality defined by naked violence. This is not particular to the plantations of Negros: rooted in colonization and slavery, the plantation as an institution has always and everywhere depended on various forms of coercion and terror, inflicted on all manner of biological life, as well as on the land itself. Some have further argued that the colonial plantation laid the foundations for the whole world order we have inherited, which means that we can trace its legacy not only in the plantations that still exist today in the Philippines and elsewhere, but also in our urban slums and our gated communities, in our war zones and our stock markets, in our prisons and our art museums. This is to say that, in many ways, we have never left the plantation.

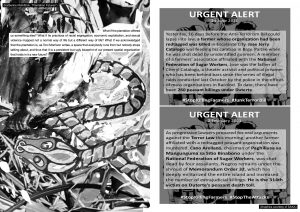

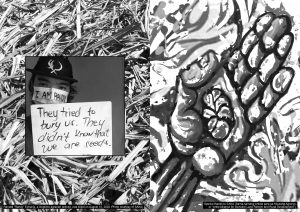

With regards to Negros, the violence of the plantation is impossible to avoid. This became glaringly clear to us a year into our research, on October 20, 2018, when nine farmer-activists were brutally massacred by a team of gunmen on a plantation in Sagay, a city that we had visited. The farmers had been setting up a protest occupation site on the plantation property, and they were eating dinner and resting inside their makeshift tent when the ambush occurred. Sadly, these nine victims are only a few out of the many hundreds of Filipinos who have died in the struggle against the plantation and its legacy.

We recount this tragic incident in order to sketch a rough picture of the urgent situation in Negros and other plantation zones of the Philippines, a situation that has only worsened under the current Duterte regime and its bloody policies. We join many others in the call to STOP KILLING FARMERS. At the same time, we do not want to propagate an abject image of Negros as an “inhuman or uninhabitable [geography],” a land of “the already dead and dying,” in the words of Katherine McKittrick. In retelling the story of the killings in Sagay, we want to draw attention not only to the hard reality of a violent system, but also to identify a logic of survival that has somehow managed to take root in these dead soils.

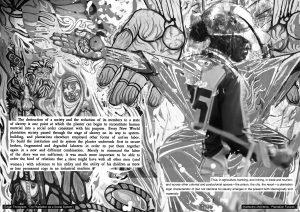

At the time of their deaths, the victims of the Sagay Massacre were engaged in a protest practice known in the Philippines as bungkalan. This is when groups of landless farmers occupy parcels of disputed agricultural land in order to collectively grow their own food crops, which generally occurs on large-scale properties that were supposed to have been broken up and redistributed under the country’s land reform program. In stark contrast to the false promises of this government program, bungkalan offers a glimpse of how genuine land reform and food sovereignty could be practiced in reality, simultaneously throwing into relief the perversity of the existing system, in which the majority of those who physically till the soil remain in a state of landlessness and hunger. Being both protest and cultivation, bungkalan is a gesture that harbors both outrage and care.

This militant activity in fact has very humble origins. For as long as plantations have existed in the Philippines, Filipino peasants and agrarian workers have been cultivating small pockets of idle land within plantation properties out of bare necessity to grow food to eat. Bungkalan has its roots in this long-standing practice. What began as a means of surviving the plantation system ripened, through the guidance and support of various leftist political groups, into an organized effort to directly confront this system. In this way, we understand bungkalan as part of an alternative history of the plantation, one that suggests links to other stories, other contexts, and one that punctures through the overwhelming sense of extinction that pervades the plantation to gesture towards an alternative future.

In tracing out this shared history, we have been especially indebted to the Jamaican theorist, Sylvia Wynter, whose writing seeks again and again to unsettle those supposedly human truths that have been produced and enforced through the dominant lens of Western thought. In her essay “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,” Wynter outlines what she calls a “secretive history” of the colonial plantation system in the Caribbean, one that is centered on the small plots of land that were given by planters to their African slave transplants so that they could grow their own food. Despite this being a direct product of the plantation system, a cost-efficient way to reproduce labor-power, Wynter emphasizes how the collective cultivation of various subsistence crops inside the plot also nurtured an oppositional mode of life, a culture that was antithetical to the dominant market-oriented system in which it was embedded. “This culture recreated traditional values—use values,” Wynter writes. “This folk culture became a source of cultural guerilla resistance to the plantation system.”

For us, the plot and bungkalan have provided a rich frame through which to think about The Angry Christ. In our work on and around this art object, we have been trying to uncover a hidden use value, to see if the mural’s queer “anger” might be radically reprogrammed towards other ends. We feel that such a (mis)reading of the mural poses important questions about the potentials of artistic practice more generally, especially as it relates to a wider project of collective liberation. For us as working artists, it has helped to unsettle certain internalized frameworks for making (and making sense of) art within the context of a heavily guarded global art system that is modeled, like so much else, on the blueprint of the plantation. We have come to understand that we have indeed never left. Given this, we seek to learn from those modes of living and persisting that have emerged from the most difficult pockets of space, and to cultivate this learning, over time and with work, into organized modes of confrontation.

These image and text materials have been excerpted from a zine produced by the artists in 2021.

The entire zine can be downloaded here:

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho: The Angry Christ (Plot and Plantation), Zine grey (PDF)

Amy Lien and Enzo Camacho are collaborating artists from the US and the Philippines and based between New York and Berlin. Their practice moves from the Philippines outwards to other places, addressing localised iterations of labour and capital from the perspective of post-colonial damage. They have had solo exhibitions at the Kunstverein Freiburg (Freiburg, Germany), 47 Canal (New York, USA), and Green Papaya Art Projects (Quezon City, Philippines), and have been included in group exhibitions at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts (Taipei, Taiwan), the Brunei Gallery at SOAS University of London (London, UK), and the Lab at NTU Center for Contemporary Art (Singapore). They recently exhibited in the 13th edition of Manifesta in Marseille, France (2020), the EVA Biennial in Limerick, Ireland (2021), the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane, Australia (2021), and the 5th New Museum Triennial in New York, USA (2021). They are current fellows at the Graduate School of the Berlin University of the Arts.