Shift the Discourse: On German Museums’ Strategies Against Decolonization

Benin bronzes, 17th/18th centuries, Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, brass. Collection of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), on display at the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem before the museum closed its doors in 2017. Photograph © Christoph Balzar.

For a long time, only the so-called experts and some activists were interested in Germany’s ethnographic museum collections. Today, those objects are at the center of debates about the history of German colonialism. Many people wonder what should be done with the inconceivable masses of objects that the German Reich and its scientists translocated from the societies that live in present-day nations like Cameroon, Togo, or Namibia, to name just a few. Contrary to many claims from the museum community, ethnographic collections cannot be considered objective repositories of knowledge about other cultures. Anthropologists with premises such as pseudoscientific race theory—the opposite of modern critical race theory—had unique artifacts robbed, stolen, and extorted from societies they deemed more primitive than their own. Many of these objects now in museum collections have significant spiritual meanings to their original owners, making them attractive to ethnographers due to their particular interests in the religions of other cultures. All European colonizers and travelers knew that such things were a profitable trade. While the cultural appropriation of museums disrupted age-old traditions in the occupied territories, this translocation was—to use an expression of modern PR—“spun” to represent the salvation of endangered cultures. The violence associated with their exhibits’ provenances was rendered invisible in the displays of ethnographic museums. Hence, white supremacy over more primitive others shaped ethnographic collecting from the start. Many white German museum professionals prefer to ignore this violence, though. They fear the loss, or more precisely, the restitution of their collections. In their eyes, restitution will eventually lead to empty museums.

“The Empty Museum.” Photograph © Christoph Balzar, 2018.

Much thought has been given to their horror vacui, to the fear of the empty museum and gaps in historical, cultural collections. However, most ethnographic objects would probably not even be eligible for restitution. Tools or everyday items such as clothing make up the most extensive parts of ethnographic collections. It is unlikely that their translocation left any significant cultural gaps in the respective societies, for they were certainly replaced after having been taken. Despite all reasoning, restitution remains a red flag for many museum professionals in Germany. For decades, these people have been exerting enormous energies to avert the moral bankruptcy of their organizations as legitimate institutions of cultural education. Their efforts to keep the restitution debate contained are so concerted that they need to be analyzed in a larger context, namely the general unwillingness of the dominant culture of German society to talk about racism. Many people in Germany are downright annoyed by the so-called postcolonialists and the museum critics for raising the issue of decolonization—first and foremost the radical right-wing parties. The strongest among these is the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which received 10.3 percent of the vote during the 2021 federal elections, even actively participating in the museum restitution debate. Key figures from the party are demanding a stop to the critical revision of the German colonial history of ethnographic museums: “The distorted image of the German colonial era as an era of ‘conquest, oppression, exploitation, looting, murder of tens of thousands of people,’ which according to [German President Walter] Steinmeier needs an ‘appropriate place in our memory,’ must be firmly contradicted.”1 German fascists want to prevent a political climate of reconciliation with postcolonial African nations, in which compensation payments in the billions become possible. They consider the decolonization of ethnographic museums Marxist ideology.

But it is not only the political right who has a hard time acknowledging German colonial history and responsibility. Instead, the historical consciousness of dominant culture is clouded across the entire political spectrum. Very few white Germans even know that another extremist context of injustice preceded Nazi rule and the Second World War. They are entirely unaware that the German Reich was a leading European colonial power before the First World War. Until recently, German school textbooks omitted this chapter of nineteenth- and twentieth-century history. German colonial rule was a mere footnote with no mention whatsoever of the atrocities committed against African nations. Therefore, it is not surprising that many white Germans still romanticize this era. Where, though, should they have learned about its horrors if not in school? Whether this blissful ignorance stems back to widespread colonial amnesia, as German historian Jürgen Zimmerer suggests, or willful forgetfulness is up for debate.2

Anton von Werner, Congress of Berlin, oil on canvas, 1881. The final meeting at the Reich Chancellery on July 13, 1878. Otto von Bismarck (representing Germany) is shown in the center between Gyula Andrássy (Austria-Hungary) and Pyotr Shuvalov (Russia). On the left are Alajos Károlyi (Austria-Hungary), Alexander Gorchakov (Russia, seated), and Benjamin Disraeli (Great Britain).

However, the historical facts about the German Empire speak for themselves. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck coordinated the European colonization of Africa with perfidious bureaucratic skill, organizing the division of the African continent among the major Western powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884. His official objective was to prevent wars between the Western nations—a measure he and his accomplices celebrated as civilized but, in essence, denied the many societies and cultures in the occupied territories their humanity. Bismarck’s dismemberment of Africa has provided the breeding ground for untold human suffering to this very day. The nations that took part in these negotiations alongside the German Reich were Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway/Sweden, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, Russia, Spain, and the United States. In other words: mainly the Global North.

Other horrors of German colonial history are similarly omitted from German textbooks and historical consciousness. These include the first genocide of the twentieth century, perpetrated by the German Empire between 1904 and 1908 in its colony of German South-West Africa (now Namibia). As punishment for the Ovaherero and Nama peoples’ resistance to German occupation, Lothar von Trotha, under Kaiser Wilhelm II, officially ordered their extermination. Only a few survived. Although today’s law clearly states that there can be no amnesty for genocide, compensation is still due to their descendants. The German government, however, diplomatically ignores them.

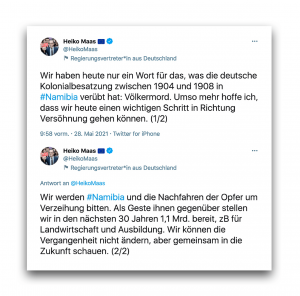

@HeikoMaas, former German Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs on Twitter on May 28, 2021: “Today we have only one word for what the German colonial occupation perpetrated in Namibia between 1904 and 1908: Genocide. All the more I hope that today we can take an important step towards reconciliation. We will ask Namibia and the descendants of the victims for forgiveness. As a gesture to them, we will provide 1.1 billion over the next 30 years, e.g. for agriculture and education. We cannot change the past, but together we can look to the future.”

In 2021, German Minister of Foreign Affairs Heiko Maas, a Social Democrat, praised development aid to the Namibian government as a grand gesture of reparation. Speaking on behalf of the Federal Foreign Office, he offered 1.1 billion euros to be paid over thirty years.3 There was more than one reason why the Ovaherero and Nama peoples boycotted the deal: First, they were left out of the talks (“Nothing about us without us” became their political campaign slogan); second, development aid is a euphemism and has nothing to do with reparations; third, the offer would have resulted in 36.6 million euros per year, which the victims’ descendants wouldn’t even receive due to the political circumstances in Namibia; and fourth, the offer was an insultingly small sum of money as compensation for a genocide. In comparison: The Federal Republic of Germany invests 60 million euros per year in its brand-spanking new ethnographic museum in Berlin called the Humboldt Forum. It was designed to look like the palace of Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was responsible for the genocide of the Ovaherero and Nama peoples in the first place. During the Humboldt Forum’s inauguration in 2020, Namibian politician Esther Utjiua Muinjangue, a Herero activist, made it very clear that this was seen as a slap in the face of the descendants of those who survived the Kaiser’s genocide. She pointed out the racist prioritization of the desires of German nationalists over the needs and rights of the Ovaherero and Nama peoples.

Esther Utjiua Muinjangue, intervention in the ruins of the palace of Kaiser Wilhelm II on December 14, 2020, virtual exhibition in the basement of the Humboldt Forum, online at www.BARAZANI.berlin/Schlosskeller.

The former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Heiko Maas, was just another German politician unwilling to talk to the descendants of genocide victims about reparations. However, his behavior demonstrates that racism is not limited to Germany’s political far-right, as many Germans prefer to believe. Left-wing politicians such as Social Democrat Heiko Maas pursue racist policies, too. However, they try to hide their racism behind political correctness. They present themselves as open to dialogue: Progressive. Postcolonial. Yet they remain capitalist: Neo-imperialist. White supremacist. Their contribution to colonial structures is only wrapped in acceptable words to sound anti-racist, as political scientist Kien Nhi Ha has highlighted. The same goes for many self-proclaimed progressive, white museum experts.

To be fair, most of these white museum experts would probably agree that all ethnographic museums with colonial collections have a racist history. They might even highlight how the museums, together with the human zoos, or Völkerschauen, indoctrinated German society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the ideology of white supremacy. Consensus with many of them ends, though, when debating the structural racism of their institutions today. They present their museums as politically progressive driving forces behind the deconstruction of white supremacy. They even write decolonial manifestos and declarations of intent. The mere performativity of this kind of anti-racist practice couldn’t be more evident than in the context of Berlin’s Humboldt Forum. Its ethnographic collections are all non-European, while its curatorial staff is all white.4 While being criticized heavily for institutionalized whiteness, anti-racist buzzwords like dialogue, partnership, and decolonization are at the forefront of the museum’s PR and social media communications. The willingness to change from a white to a postcolonial institution is signaled but doesn’t exist.5

Call for contributions by the Humboldt Forum for a magazine entitled Decolonise, @HumboldtForum, Instagram, 2021. The page was deleted in March 2022, presumably due to negative public response.

This hypocrisy stems back to a lack of self-awareness by many such museum experts that only extends to what philosopher Sara Ahmed describes as the boundaries of their white comfort zones.6 White people feel comfortable in white institutions where everything supports their experience as individuals allegedly without race. Consequently, they identify strongly with institutions that suit their desires, but they fail to acknowledge—let alone reflect on themselves as being part of—structural racism. Ahmed also explores the emotional reactions when the invisibility of whiteness is called out and made visible. As a result, white people avoid unease in their comfort zones and will protect their institutions. To shift the discourse is a typical defense of German ethnographic museums.

As early as the 1970s, a Pan-African decolonial movement was already gaining momentum.7 Embedded in a global vision for a free Africa, one of its goals was to reclaim looted cultural objects from the museums in the Global North. Art historian Bénédicte Savoy recently determined why this movement had been unsuccessful with its requests to the ethnographic museums for restitution: The museum directors in Germany conspired against it. A confidential memo made the rounds with practical tips on defending against restitution.8 For example, they replaced terms like “loot” with more innocuous-sounding expressions like “transfer” in their PR communications.

Consequently, it became much more difficult to talk about restitution. By secretly boycotting the decolonial movement in its early stages, white museum directors successfully protected their institutions, collections, ideals, careers, opportunities, and reputations. But this action is by no means all that German museums and their staff have undertaken ever since to safeguard their interests: to deflect anti-colonial critique, museum directors and experts keep coming up with new terms and expressions for the word “loot,” giving it an appreciative ring to shift the discourse on restitution.

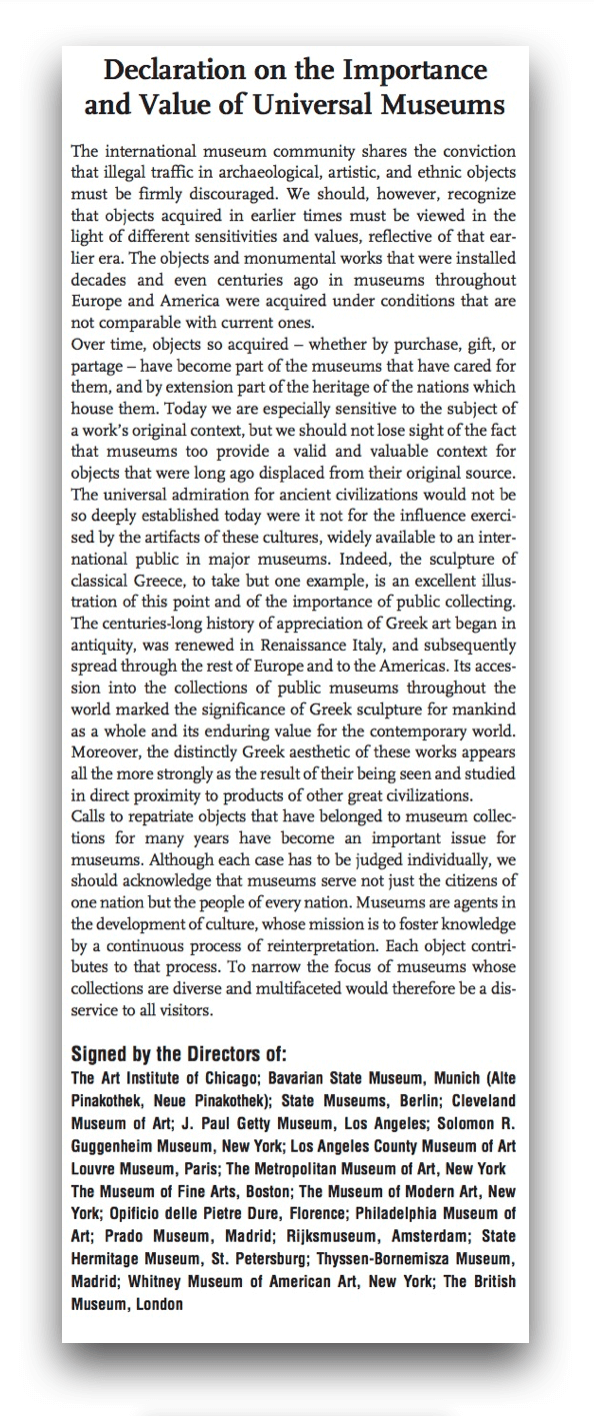

In 2002, various large museums from the Global North declared their colonial collections part of “world heritage.” They even wrote a manifesto: “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums.”9 The list of institutions that took part ranged from the British Museum in London to the Louvre in Paris and from the Museum of Modern Art in New York to the State Museums in Berlin. Their claim was as follows: Because they had made their exhibits accessible to an international public for so long, those collections automatically became a “world heritage” and the property of the world. But only museums can adequately preserve and present a “world heritage,” because it must be accessible to the whole world. And what other institution could guarantee that? Therefore, all claims of the societies of origin merely reflect their respective national interests and should be given less weight.

It was a brazen move, not least because museums do not have the right to declare anything a world heritage in the first place: this right is exclusive to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In his analysis of the Universal Museum Declaration, Kenyan museologist George Abungu started an eye-opening debate about the museum community’s greatest fears, imperial megalomania, and white saviorism. The “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” was silently buried. But it did not take long until the museums came up with a new PR strategy.

“Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” inter-institutional museum manifesto, 2002. Signed by museums across Europe and North America, this manifesto advocates for museums as universal institutions that hold world heritage in one place on behalf of humanity, stating: “We should acknowledge that museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.”

What the self-proclaimed “universal museums” had previously called a “world heritage,” began to be presented as a “shared heritage”—another term appropriated from UNESCO’s vocabulary.10 Palestinian and Israeli academics refer to specific natural landmarks or areas of cultural heritage in the region as a “shared heritage.” By doing so, those peacemakers attempt to establish an awareness for each other’s needs. When applied to the museum context, though, the concept becomes a caricature of itself: Those who use the term suggest that colonial museum collections should, at best, be kept in the museum as it is only there that all interested groups are able to access them for the purposes of research. However, it is doubtful that such a unilaterally articulated concept of sharing will ever contribute to settling conflicts over colonial museum collections. Taking the idea further clarifies the absurdity: members of formerly colonized societies from distant countries such as Australia would need to achieve the logistically impossible whenever they needed to access their cultural heritage, say for traditional ceremonies, as they would have to travel to, for instance, Germany. In the context of museums, the concept of shared heritage represents yet another attempt to shift the discourse on restitution, only this time with a stronger emphasis on virtue-signaling.

Excerpt from the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation website, www.preussischer-kulturbesitz.de, accessed March 1, 2022.

German museum ethnographers have recently taken their rhetoric to the next level. Now, they are stressing that their collections have always been art collections (making the ethnographers art curators). Supposedly self-critical, they point out that earlier ethnographic curators had denied non-European societies the ability to create art because of their racist prejudices. They proclaim that non-European cultural objects have never been inferior to European masterpieces but are equal in value. This portrayal of art historical penance is brilliantly deceptive. It first became evident in 2019, when the State Museums of Berlin installed highlights from their African ethnographic collection next to European works of art. The exhibition in Berlin’s renowned museum of antiquities was titled Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode-Museum. The curatorial concept entailed installing various pairs of objects from the collection from Europe and Africa. One prominent example was the juxtaposition of a bronze putto by Italian Renaissance artist Donatello with a statue of the goddess Irhevbu or Princess Edeleyo from the Kingdom of Benin, yet, without indication of authorship.

Installation view: Putto by the Renaissance-period Florentine sculptor Donatello juxtaposed with a “a statue of the goddess Irhevbu or Princess Edeleyo.” Photograph © Christoph Balzar, 2018.

The curators explained that the African statue from the Berlin collection had until recently been relegated to the second rank of the ethnographic museum. Now, it was given due appreciation in the art museum. They claimed that they had finally solved the problem of discriminatory ethnographic museum displays: The contested objects need to be installed in another museum, the better museum, the art museum. However, art museums are no less alienating for a looted African statue than an ethnographic museum. The reclassification of the goddess Irhevbu or Princess Edeleyo as a work of art cannot convey knowledge to a museum’s audience about what she means to her community any better than her former ethnographic classification. It only shifted the frame of interpretation from one Eurocentric discipline of object knowledge to another, namely from European ethnography to European art history. Not one Nigerian museum expert, let alone a traditional owner from the kingdom of Benin, was given an opportunity to say anything at this exhibition about what was being presented. Only white people curated this art exhibition. The question of why such looted treasure is in a German museum remained entirely untouched (as if the topic of restitution was to be avoided at all costs).

Since the creation of museums in the nineteenth century, art museums and ethnographic museums have been conjoined by the racist project of segregating the world’s population at an epistemic level: white Europeans put their creative achievements in art museums and those of non-whites get put into ethnographic museums. Both types of museum have condoned the racialization of people in their own ways and grown up in harmonious difference to each other. This is not to say that non-European societies today do not also pursue independent artistic practices. On the contrary, they do so very actively against the background of their transmodern notions of art, as the art historians Susanne Leeb and Christian Kravagna have pointed out.11

Nevertheless, art in the sense of what is negotiated on the art market remains a concept that cannot be applied retroactively to objects like the looted Benin bronzes. Making art is an aesthetic practice involved with making things that are supposed to be primarily looked at. But this visualistic configuration of cultural objects did not exist in the colonized territories before colonization. Instead, there were other aesthetics of looking at things, which had special significance but not the central one as in the world of Western art-making. The aesthetic practice that brought forth the statue of the goddess Irhevbu or Princess Edeleyo revolved around political rituals and religious ceremonies in the Royal Palace of Benin. The exhibition’s curators even highlighted how British soldiers brutally plundered the Bronzes from their context as spoils of war before selling them to Germany. The curators also mentioned that the Bode Museum has treated European political and religious artifacts like Christian icons equally by aestheticizing them. This is all true, but it does not retroactively legitimize the museums’ history of cultural appropriation and aesthetic reprogramming of performative objects. In fact, museums are aesthetically incapable of grasping the performative aspects of culture. After all, it is their function to aestheticize things once they are taken out of context so that their audiences can enjoy looking at them. Consequently, most people demand the restitution of ethnographic museum objects because their ancestors did not intend their creations to be only looked at. They fight for restitution, to serve their deities after years of involuntary separation, to stop offensive behavior by museum staff, or to bring about justice or peace of mind to the families and communities. Therefore, the notion of art that many German museum experts use to reclassify ethnographic objects as art objects is not only inappropriate, it amounts to neocolonialism. Its purpose is to keep the loot in the world of museums (where art belongs) to regain control over the restitution debate, and to remain in power.

With this strategy of shifting the discourse, white museum experts have already been derailing the restitution debate for over fifty years. They keep forcing rightful owners of colonial loot into ever new discussions, boring conferences, and cooperation projects. For as long as there is debate, they can publicly justify the continuation of their institutions.

Ethnographic museums with collections made up of objects of the colonial period have been set up by white people for white people. As a result, they have institutionalized a specific visualistic aesthetic that is historically interlinked with the white gaze. They remain white even with a diverse staff. Diversification will not change these institutions by default, only who operates them. The mission of educating people about other people by using colonial loot will always remain dehumanizing. It is as simple as it is complex. Germany’s ethnographic museums cannot be decolonized. The racism emanating from these institutions may be contained, though. Just as Germany could not de-Nazify concentration camps but was able to turn them into memorial sites, likewise society should deal with the former colonial museums, the ethnographic museums, by abolishing them and turning them into memorial sites—into museums of colonialism. While the ownership rights to unlawfully acquired objects need to be transferred to the societies of origin, the panoptic gaze of the ethnographic museum must be turned toward itself, thus facing the horror vacui of whiteness.

Christoph Balzar is an art theorist and curator focused on the development of museums in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, historical collections, and political activism. Balzar organizes socially engaged art projects and exhibitions nationally, internationally, and online. www.ChristophBalzar.com

Footnotes

1 “Dem Zerrbild der deutschen Kolonialzeit als Ära von ‘Eroberung, Unterdrückung, Ausbeutung,

Raub, Mord an Zehntausenden Menschen,’ die nach [Bundespräsident Walter] Steinmeier einen ‘angemessenen Ort in unserer Erinnerung’ benötige, muss entschieden widersprochen werden,” see Marc Jongen, “Humboldt-Forum: Mehr Debatte Wagen!,” press release, September 24, 2021, https://marcjongen.de/pressemitteilung-jongen-das-humboldt-forum-muss-mehr-demokratische-streitkultur-wagen, accessed March 22, 2022. 1

2 Jürgen Zimmerer, “Keine Geiseln der Geschichte. Deutsche Kolonialherrschaft ist bloß eine Episode, denken viele. Das Dritte Reich zeigt: Dauer sagt nichts über Intensität,” TAZ, January 10, 2014, https://taz.de/!808947, accessed January 29, 2021.

Jürgen Zimmerer, “Kulturgut aus der Kolonialzeit – ein schwieriges Erbe?,” Museumskunde, vol. 80, no. 2 (2015), pp. 22–25. 2

3 @HeikoMaas on Twitter, May 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/heikomaas/status/1398186805648891907?lang=en, accessed May 29, 2021. 3

4 As of October 22, 2022. From an interview with Hartmut Dorgerloh, director of the Humboldt Forum, see BARAZANI BERLIN—Forum Colonialism and Resistance, http://www.BARAZANI.berlin/weisse-dominanz, accessed January 17, 2020. 4

5 Sara Ahmed, “Declarations of Whiteness: The Non-performativity of Anti-Racism,” Borderlands e-journal, vol. 3, no. 2 (2004), p. 16, http://ww25.borderlands.net.au/vol3no2_2004/ahmed_declarations.htm?subid1=20220506-1644-4212-88b1-30bc8584961b>, accessed February 23, 2017. 5

6 Sara Ahmed, “A Phenomenology of Whiteness,” Feminist Theory, vol. 8, no. 2 (2007), pp. 149–68, here p. 165. 6

7 As curator Ibou Coulibaly Diop highlights in his work: see, for example, the Organization of African Unity (eds), La culture africaine, le symposium d’Alger, 21 juillet–1er août 1969, Algiers / African Culture: The Algiers Symposium, July 21–August 1, 1969, Algiers, Addis Ababa, 1969. 7

8 Bénédicte Savoy, Afrikas Kampf um seine Kunst. Geschichte einer postkolonialen Niederlage, Munich, 2021, p. 100. 8

9 “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums,” inter-institutional museum manifesto, 2002. Interestingly, the manifesto has been more or less deleted from all the sites where it was originally published, but it can still be accessed on the website of the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/news/news-item/news/1999_2013/hm11_1_93/?lng=, accessed January 17, 2020. 9

10 Elizabeth Ya’ari, “Promoting Understanding of Shared Heritage (PUSH),” Museum International, vol. 62, no. 1–2 (2010), pp. 9–13. 10

11 Susanne Leeb, “Die Kunst der Anderen. ‘Weltkunst’ und die anthropologische Konfiguration der Moderne,” PhD diss. Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt, 2007, https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-euv/frontdoor/deliver/¬index/docId/69/file/leeb_susanne.pdf, accessed January 29, 2021, p. 280/26, quoted from Hans Belting, Bild-Anthropologie. Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft, 6. Munich, 2001, p. 6; and Christian Kravagna, “Für eine postkoloniale Kunstgeschichte des Kontakts,” Texte zur Kunst: Globalismus, vol. 91 (September 2013), pp. 111–32, here p. 115. 11

May 13th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04