Screens, Layers, Algorithms: A Conversation with Ho Tzu Nyen

Since the early 2000s, the Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen (b. 1976) has been making film and video works that often feature striking, purpose-built installations. Shown at contemporary art biennials and museum exhibitions in Asia, Europe, and, increasingly, the United States, Ho’s work explores Southeast Asia and its histories. Not culturally or linguistically unified, Southeast Asia is the geographical subregion of Asia that encompasses the present-day nation-states of Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. Southeast Asia is a “shapeshifting region,” Ho emphasizes, drawing attention to these countries’ shared entanglements via their colonial histories and the presence of imperial Japan in the region during the Pacific War. Drawing on mythology and folklore, Ho intermingles ecological, cosmological, and even supernatural elements with the region’s political and wartime histories. Ho’s imaginative histories of Southeast Asia are not only a foil to Southeast Asia as a Cold War geopolitical construct—the context of the region’s original grouping—these histories also agitate the neoliberal visions of the region’s contemporary governments.

A sprawling archive of moving images shore up Ho’s complex histories. His video works since 2015 have involved a combinatory aesthetics of appropriation, for which the cinema and the internet are primary sources of material. The historical layers that Ho parses are reflected in the form and materiality of his video installations. Owing to Ho’s use of multiple screens of different materials and varying transparency, the screen is not just a projection surface but a tangible form of materiality. Since 2019, Ho’s works have also included distinctive 2D animations. These animated images feature forms of layering that he regards as a metaphor for history. Owing to Ho’s work with North Korean animators, the creation of these animations involves unique processes of collaboration and delegation. Such processes further complicate the notions of borrowing and deferred authorship that undergird his appropriationist aesthetic.

In the conversation that follows, Ho introduces his practice through a discussion of three recent productions: the algorithmic video work, The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia (2017–ongoing), the site-specific installation Hotel Aporia (2019), and the exhibition Night March of Hundred Monsters (2021–22).

The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia is primarily accessible to viewers as an interactive website at http://cdosea.org. Toggling through the tabbed alphabetic entries on the web page—such as “A” for “altitude” and “anarchism”; and “P” for “padi,” “politics,” and “plateau”—yields different combinations of video images and sound. The work has also been shown as a video projection in exhibition and museum spaces.

Screenshot from CDOSEA, 2017, algorithmically composed video, infinite loop. Created in collaboration with Sebastian Lütgert and Jan Gerber. Vocals by Bani Haykal. Commissioned by the Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong).

Made on commission for the 2019 Aichi Triennale, Hotel Aporia is a site-specific video installation that occupied four rooms in Kiraku-Tei, a disused Japanese-style inn and hotel in Toyota City. Popular from the 1910s to the 1980s, patrons of Kiraku-Tei were representative of the area’s shifting demographics. Featuring six video screens and thirty audio channels, Hotel Aporia investigates the histories of the Second World War in Japan and Southeast Asia through imagined and actual guests at the hotel, such as the twentieth-century Kyoto School philosophers and the filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu.

Finally, the exhibition Night March of Hundred Monsters centers on the transmogrifying nocturnal entities from Japanese folklore known as yōkai. On view from October 23, 2021 to January 23, 2022 at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, Toyota City, the exhibition comprised four video works in four rooms, which were meant to be navigated via a linear, sequential pathway. These video works depict animations of yōkai and historical figures whom Ho reimagines as yōkai, such as the general Tomoyuki Yamashita—the “Tiger of Malaya”—who led the Japanese army to swift victory in the 1941–42 invasion of Malaya. One such work is the two-screen video installation 100 Monsters (2021). Through a translucent screen featuring sleeping figures, the viewer sees yōkai parading in single file on a second screen that mimics the proportions of a scroll painting. Another video work featuring yōkai is 36 Ghosts (2021), an animation of these creatures that is projected on a glass surface, which serves both as a screen and a mirror.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the viewing copy of the video work and documentation of the exhibition space frequently substitute for in-person experience. Even under such circumstances, when dematerialized and miniaturized on a laptop display, Ho’s moving image combinations still touch and astonish. And despite these viewing challenges, the cloud platform Zoom as a kind of meta-medium produces new instances of collective viewing and international exchange. The following conversation speaks to the possibilities of making and viewing moving image installations in such times of remote access.

How did you conceive The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia?

One central concept running through The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia is Southeast Asia as a kind of shapeshifting region. And I would say this probably came out of my engagement with some of the terms within the Dictionary. I think the first two terms that I engaged with intensely were “T” for “tiger” and “L” for “Lai Teck.”

“T” for “tiger” was a project looking into the history of tigers across Southeast Asia. Tigers dispersed themselves across Southeast Asia more than a million years ago, when Southeast Asia was still a single landmass known as the Sunda Shelf, which is also to say that tigers were in Southeast Asia before Homo sapiens even emerged. I found it very interesting that in many parts of Southeast Asia, there is the animist belief that tigers are related to one’s ancestors. Particularly in the Malay part of Southeast Asia, tigers are seen as vehicles or mediums for ancestral spirits. And, in a way, I think it’s true—because tigers were here before Homo sapiens. Just like Europe has its werewolves and Latin America has its werejaguars, Southeast Asia has a belief in weretigers; shamans can transform into tigers. So for me, the tiger is essentially a metamorphic animal––something that oscillates between the human and the other. If we pursue the history of the tiger and how it has changed over the ages, the tiger is not simply the other, an animal that is nonhuman, it is something that is in between. To think of the tiger, its ability to transform, the metamorphic process, is also very close to not having a fixed image. This mutability within the image of the tiger interested me as a motif.

Documentation of One or Several Tigers, 2017, synchronized double channel HD projection, automated screen, shadow puppets, 10 channel sound, show-control system.

The other term that I explored at the beginning of the project was “L” for “Lai Teck.” Lai Teck was the secretary general of the Malayan Communist Party from 1939 to 1947, and he was also, in 1947, unveiled as a triple agent. He worked for the French secret police; he was originally Vietnamese, then he worked for the British secret police and the Japanese secret police. So, for me, Lai Teck is also an important embodiment of what Southeast Asia could have meant at a certain time. And he was also a shapeshifter. These two terms very much contributed to my own eventual casting of this region itself as a shapeshifter.

I started researching this project quite a while ago, in 2012. My basic interest and curiosity were about what Southeast Asia—a region that has never been unified by language or religion—is. What makes Southeast Asia a region? What constitutes its unity? What is the inside? What is its outside? I was gathering concepts and notes for a long time, looking for different ways of approaching this question. But it took me quite a while before I came to this solution of using the algorithms to constantly, I guess, “scramble” and “reassemble” the work.

I would characterize most of my video works as being pre-composed. The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia—we usually refer to it as the CDOSEA, in short form—is an exception, in the sense that it uses an algorithm to compose the image as well as to select the soundtrack. To provide a bit more context: the work draws from an archive of images, all of which are derived from online sources (YouTube, Vimeo, or illegal torrent websites). We created an algorithm that selects from these images. And at the same time, it chooses between ten different versions of voice-overs that are performed in ten different ways. So, it matches these images with the voice as well as a background soundtrack, so that the film is—theoretically—never truly repeated; it keeps transforming.

I thought that the only possible type of work about a shapeshifting region is a work that can itself shapeshift. If I had made a finished film which doesn’t change, it would inadequately stand as a representation of a region which, even as we are speaking, is dynamically transforming all the time. My solution was not to think of the work as a representation but to think of it as a model—how to model transformation and the region’s metamorphosis rather than try to capture it at one fixed point. And this is where the algorithms come in.

The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia is both a project in itself and a generator of other projects. The website is an algorithmically edited film, but the Dictionary itself is also a kind of meta-project: I also produce projects based on the individual terms in the Dictionary. For example, generated from the Dictionary were works like One or Several Tigers (2017), a video installation with two screens; there’s also the theatrical performance Ten Thousand Tigers (2014). In this way, I use the Dictionary to generate different projects across the various mediums I work in, from installations to performances to, sometimes, film.

Documentation from performance Ten Thousand Tigers, 2014 to 2016.

Could you say something about CDOSEA’s soundtrack, which features both vocal music and field recordings?

The sound is a really important component of the work for me. Sometimes I think I make images in order to have the excuse to incorporate sound. The voices were provided by a super-talented Singaporean multi-instrumentalist and vocalist Bani Haykal. I provided ten versions of different texts for each letter of the alphabet, and I also wrote descriptions of ten different ways of performing them. But my instructions were always rather cryptic, intentionally so—so that Bani had full freedom to explore these different ways of performing each of the texts. The field recordings were done by a Japanese collaborator and friend, Yasuhiro Morinaga, who spent a lot of time in different parts of Southeast Asia doing field recordings of different types of ethnic music, so they’re mostly composed of the various types of music typically found around Southeast Asia. Most sounds are produced by bamboo instruments or gongs, which I see as the two iconic Southeast Asian musical instruments.

We have created a library of these field recordings. The algorithms which are editing the films are, at the same time, selecting clips from these audio libraries and combining them; the algorithm picks parts of these different samples and mixes them in real time. But we can’t really hear these recomposed sounds on our computers, because we need a 5.1 surround-sound system in order to make this portion of the soundtrack audible, which we achieve when we install this work in a physical space. That’s when the soundtrack becomes much more obvious. A little bit of the music does spill over onto our stereo systems, but it is not as clear as when I install it in a physical space.

Is this a closed work, or is it “live” and “growing”?

We built another online platform behind the Dictionary. With my collaborators, we continually add new material, new videos, and we can change the sound. We are always updating the images, sometimes even feeding other projects into the archive, ones that I have done which are themselves generated by the Dictionary, projects on the individual terms in the Dictionary, for example. I think it is important to make projects that can continuously change with time.

I should add that the version on the website is a restricted or limited version of the larger CDOSEA. This is simply due to the capacity of the website. It still varies with every viewing, but there is a certain limit to the total number of combinations it can make. When we show it in a museum or gallery, we show it with a minicomputer, so every loop it shows is without repetition.

The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia, Volume 3: G for Ghostwriter, single channel video, surround sound, LED Lights, algorithmic editing system. Installation view at Hamburg Kunstverein.

Hotel Aporia (2019), the site-specific video work that you created at the currently unused Toyota City hotel and inn Kiraku-Tei, was regarded by critics as a key work at the Aichi Triennale that year. How might one begin to think about this complex work on Japan and the Pacific War of 1941–45?

One way to describe the work Hotel Aporia is as a hotel to which I invite all these different guests. In cinematic terms, we might call it a multi-narrative film where you follow the trajectories of different protagonists. These protagonists might not necessarily cross paths, but rather, what interests me is a kind of resonance between each of the guests.

Maybe we could start with the name: “Hotel” is obvious—because we are using a site which really used to be a hotel. In Japanese, it would be known as a ryokan, a traditional inn. And as for the word “aporia,” this was related to how Japanese aggression in Asia was seen within Japanese discourse of the early twentieth century leading to the Second World War. There were, of course, discourses which were very openly imperialistic and aggressive, but there was also this other, I would say, Pan-Asianist and utopian strand in which, essentially, it is claimed that they wanted to invade other parts of Asia in order to liberate them from colonization. I use aporia to represent this kind of unresolvable contradiction—between this sort of utopian line and the imperialistic line—which, for me, exist simultaneously. I guess that’s another framework by which we can understand some of my starting intentions for Hotel Aporia. It was also about gathering all these different guests with their various experiences of war and differing ideologies, and tracking what they did over the course of the war.

Hotel Aporia, 2019, 6-channel video projection, 24-channel sound, automated fan, lights, transducers and show control system. Installation view at Kiraku-Tei, Toyota City. Photograph © Hiroshi Tanigawa.

One group of guests that were important for me was the group of philosophers known as the Kyoto School. They were regarded as the most significant Japanese philosophical circle of the early twentieth century, but their reputations plummeted drastically after the Second World War. They were said to be aligned with the ultra-nationalist, imperialist cause. I would say it’s not entirely untrue, but the situation is also much more convoluted than that. The central protagonist of the Kyoto School is their so-called founder, Kitarō Nishida (1870–1945). He was usually regarded as the most important Japanese philosopher of the twentieth century—one of the first to put Western and Eastern philosophy into creative and rigorous dialogue; you could say that his philosophical mission was an overcoming of Western philosophy. So, it is an interesting parallel to look at Nishida’s project and also at how Japan was itself trying to overcome the West militarily during the Second World War. The roots of Nishida’s philosophy, although I’m simplifying immensely for conversation’s sake, is zettai mu, which we can translate as “absolute nothingness.” It’s a concept that is very closely related to Nishida’s lifelong interest and practice in Zen Buddhism, and, for him, it is a fundamental ontological concept.

If we think about concepts of nothingness in relation to Zen and Buddhism, our initial assumption might be that it is a pacific religious idea. But on the contrary, during the Second World War, many Zen monasteries were pro-war… Zen is also very closely aligned with the samurai spirit. We can also think about Zen and the art of archery; a lot of exercises related to Zen are also arts of killing. Between 1942 and 1943, the four Kyoto School philosophers I chose to “invite” to Hotel Aporia had been involved in a roundtable discussion, and the three rounds of discussions they had were published and extremely popular in Japan at that time. We could describe what they were trying to do not as an attempt to stop the war but to swerve the war towards what they thought of as a higher moral purpose. It is interesting to think about nothingness and how nothingness can be used and abused in different ways in this context.

Still from Hotel Aporia, 2019, 6-channel video projection, 24-channel sound, automated fan, lights, transducers and show control system.

Another very important guest in the work is the filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu (1903–63). Between 1943 and 1946, Ozu was actually in Singapore—that was something I was always very curious about. It’s also well known that Ozu was sent to Singapore to make a propaganda film, but he never made the film—it’s always been a mystery to me why he didn’t make the film. I’ve read some reports that say that he had a good time in Singapore; he was swimming, playing tennis, having parties. But none of these accounts can really be verified. But I think Ozu has been on record as saying that he saw a lot of films there which were confiscated by the Japanese military, like American films. He saw Citizen Kane (1941), which was very influential for him… . So, I also wanted to track what Ozu was doing. I would say seventy percent of the footage from Hotel Aporia came from Ozu films.

Still from Hotel Aporia, 2019, 6-channel video projection, 24-channel sound, automated fan, lights, transducers and show control system.

How did you conceptualize and create the installation in the ryokan?

One of the main reasons I decided to work with Ozu as the main source of the work’s images was because, when I first visited the site, I realized that it was a very difficult space for doing video projections. In the traditional Japanese house, the proportions are such that the ceilings are very low. It made me think about how projections were really meant for a different kind of space, the museum space, usually built to European proportions. Trying to squeeze projections into the space of a ryokan is difficult, which is why I decided in the end to have all the projection screens start from the floor, from the ground; the audience thus has to watch the films seated low on the tatami on the ground. And Ozu is very famous for his low camera angles, because all his protagonists are seated on tatami—so this focus on floor level in Ozu’s film perspectivally matches up quite perfectly with the height the audience are seated at in Hotel Aporia.

Hotel Aporia, 2019, 6-channel video projection, 24-channel sound, automated fan, lights, transducers and show control system. Installation view at Kiraku-Tei, Toyota City. Photograph © Hiroshi Tanigawa.

All the lines of inquiry in Hotel Aporia take the form of a letter or email exchange between myself and my Japanese collaborators. The people who participated in the conversation were my curator, my researcher, as well as my translators. This process was the only way I could see myself engaging in a project about these still very sensitive questions of Second World War history in Japan. I wanted to make my own limitations very clear: I don’t speak Japanese, yet I was dealing with this subject matter. Having the translator woven into the conversation was a way of making that process clear. My own role was almost as a kind of catalyst—to start these different lines of inquiry with my researchers, the curator, the translators—and then to find a way to put it all together in the end. Using the format of the email exchange allowed us to use a relatively simple and straightforward language to discuss concepts and histories that were otherwise very convoluted and complicated. When we try to sum up what we read and think in an email to someone else, we are free of a lot of anxieties. That was why I chose the format of the letter exchange, which I decided on quite late in the process.

Your recent exhibition Night March of Hundred Monsters at Toyota Museum of Art centers on the yōkai of Japanese folklore—shapeshifting creatures that can adopt humanoid form, animal characteristics, or even the appearance of inanimate objects. Can you speak about this choice of motif?

First, I think I should add a couple of sentences on the word “monsters.” “Monsters” is not the best translation of the Japanese word “yōkai”—which is as untranslatable as, perhaps, “sushi”—the range of possible meanings are specters, demons, monsters, even minor gods… . Yōkai have a long history in Japanese folklore, and they were massively commercialized after the war in the twentieth century. This means that you’ve probably seen yōkai before without being aware of them as yōkai: kitsune the nine-tailed fox; tanuki the racoon dog; kappa the frog—are some of the most popular ones. One of the main experiments I was trying out with the exhibition was splicing this history of the yōkai, which is popular, with Japanese wartime history, which is not so popular.

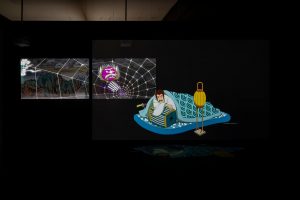

100 Monsters, 2021, 3 channel video installation, 6 channel sound. Installation view in the exhibition Night March of Hundred Monsters at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. Photograph © Hiroshi Tanigawa.

Who were the animators you engaged for the video works in Night March, and how did you work with them?

One of the main collaborators on the exhibition was an animation studio known as Screen Breathes Studio—not their real name, because the studio is located in North Korea. It’s complicated to collaborate on a project with North Koreans. I first worked with them in 2019 with the video and sound installation The 49th Hexagram (2020), which was basically a collection of South Korean films that show different historical protests from the last hundred years of Korean history. These were South Korean cinematic representations of protest. I extracted film stills and recomposed them into a storyboard that I got the North Korean studio to reanimate as a new work.

36 Ghosts, 2021, single channel video on mirrored screen, 6 channel sound, automated lights. Installation view in the exhibition Night March of Hundred Monsters at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. Photograph © Hiroshi Tanigawa.

Then I decided to continue my collaboration with the North Korean studio for the exhibition Night March. I would say that one of the main reasons I liked collaborating with them was precisely how difficult communication was. Zoom isn’t possible for North Koreans; I could not send them an attachment any larger than two megabytes. All the typical ways, all the conveniences we take for granted in collaborating with other people, we had to put aside and figure out a different means of working together with these very special animators. Of course, there is a long and painful history between Korea and Japan as well, so it was interesting for me to engage a North Korean studio to work on a project very much centered around Japanese wartime history. And this relationship is interesting, because you can see from the North Korean animation style that they were also, I would say, influenced by anime. There is a kind of dialectic going on in their relationship to Japan. So, I started using my projects and their processes to facilitate these strange types of exchanges.

I hardly ever spoke to the North Koreans. I haven’t had the chance to ask them if they’ve seen anime films like Ghost in the Shell (1995) or Akira (1988). All our communications go through a third party, “Sirius Black,” named after a character from a Harry Potter novel. I’ve been in conversation with Sirius Black for more than two years now, but I’ve no idea who he, she, or they are—I have no idea how many animators work on my project… . They are completely faceless to me. But at the same time, we have developed a strange kind of friendship over the years; or maybe I am over projecting. But I regard it very much as a close collaborators’ relationship. Most of the time, I have to make sure my documents are small enough to be sent through. I also give them a lot of autonomy in creating the final shape or form of the images.

The animation industry in North Korea is a rather large industry that has been ongoing for a long time. Quite a number of European studios secretly farm out their work to North Korean studios. In animation, you have two kinds of frames: key frames, the most important frames that determine the flow of the action, and the in-between frames, which continues the movement. In-between frames are the kinds of frames that the North Korean animators produce, which involve manual or repetitive work. But I usually give the North Korean animators very broad parameters, to see what they can do and what they’ll produce with their imagination. That was what I was curious about at the beginning: seeing what they would imagine.

I hope to visit Pyongyang one day to meet them. I was supposed to meet them around the time that the COVID-19 pandemic started, but I would have been stuck for maybe six months in Pyongyang without internet!

Character design for the Two Tigers of Malaya (General Tomoyuki Yamashita and the bandit Tani Yutaka).

What kind of animation does Night March feature? What kind of image does this technique of animation yield?

If we think of, for instance, Pixar animation today, it is all 3D animation, the “new technology.” Classic Japanese animation is instead defined by flatness, and we usually call it 2D animation. In the last three years, I got very interested in 2D animation, precisely because of the limitations it forces upon you. For example, having a character rotate in space in 2D animation is the most difficult thing to do. In 3D animation, you have a virtual model and a virtual camera that you can move around the model quite easily—all 360 degrees of space is open. On the other hand, 2D animation requires a kind of translation and reimagining of “real world” movement into two dimensions. What defines 2D animation is the art of layering, arranging flat layers. The term we would use to describe this kind of image-making is compositing, which we can think of in opposition to composition. While a picture is composed, compositing is an arrangement of an image in layers. Something about compositing fascinates me greatly.

If you think about the key characteristic of anime, as opposed to early Disney animation which was also 2D, it is the relative poverty of movement. Walt Disney was always trying to compete with cinema. In the big Disney productions, there was always a depth of field; all the layers move together in a very naturalistic way. But in Japanese anime, movement is much more minimal. You sometimes only have one, two, or three layers. You don’t have the budget to create a lot of moving parts. But what the Japanese animators do is that they exploit this layering by sometimes pulling apart the layers within the image. You sometimes have this strange kind of effect where layers within a single image are drifting apart, creating a strange and unnatural but powerful kind of affect for me. Sometimes I would have layers of animation on top of found footage or archive images, and I would switch the layers below or the layers on top to intensify the feeling of the layers.

This is one of the things that fascinates me about Japanese anime: minimal movement, maximum intensity. To create maximum intensity, the Japanese animators sometimes tap into eroticism or even an aesthetic of perversion and hyperviolence. But anyway, I started to imagine our image of history as a kind of composite: that is, what happens if we think of working with history in terms of peeling these layers apart? What looks from one perspective like an almost natural image starts to become strange, because we are adjusting the layers and shifting perspectives. I’m not sure if any of my work actually achieves this, but it’s still a working model for me.

Can we think of the layer as harboring a void?

It’s the gaps between layers. What’s the difference between a gap, an interstitial, and a void? I think it is interesting to think of a genealogy of emptiness, nothingness, the void. Do they all mean the same thing, or are they different? These are the questions that have interested me when thinking about animation.

This dialogue was recorded on February 22, 2022 as part of the online lecture and conversation series Coincidences in Prepositions. The dialogue has been edited and rearranged for the purposes of publication.

Ho Tzu Nyen (Singapore, b. 1976) earned a BA in creative arts from Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne (2001), and an MA in Southeast Asian studies from the National University of Singapore (2007). He has had solo exhibitions at such venues as Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (2021); Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (2021); Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art in Oldenburg (2019); Kunstverein, Hamburg (2018); Ming Contemporary Art Museum (McaM), Shanghai (2018); TPAM, Yokohama (2018); Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong (2017); Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain (2015); Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2012); and Artspace, Sydney (2011). He has also participated in group exhibitions at National Gallery, Singapore (2018); Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2017); Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (2016); Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), Brisbane, Australia (2016); Times Museum, Guangzhou, China (2013); and Witte de With, Rotterdam (2012). He participated in the Gwangju Biennale, South Korea (2020, 2018); Sharjah Biennial 14, United Arab Emirates (2019); and the 54th Venice Biennale (2011), where he represented Singapore. His films have premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, Sundance Film Festival, and the 66th Venice International Film Festival.

Ying Sze Pek researches global modern and contemporary art with a specialization in the histories of photography and time-based media. Her areas of interest include media theory, the history of global art exhibitions, and art in Europe since 1900. She is a PhD candidate at the Department of Art & Archaeology, Princeton University where she is completing her dissertation, Reality Expanded: The Work of Hito Steyerl, 1998-2015.

May 13th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04