Resurrecting The Dead: Decolonial Practice by Akademi Jawi

In their book On Decoloniality, Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh point out the need to scrutinize existing academic disciplines by looking at the formation of that discipline and what it entailed. This requires revaluating the concept and the vocabulary being used, which is understood as never neutral, neither in value nor intent. Most disciplines are permeated with the Western worldview, especially the ideals of the European Enlightenment, which have been surreptitiously used as a tool to define and research even wholly non-European fields of study. Mignolo and Walsh further explain that: “Eurocentred knowledge asserts itself and at the same time disqualifies other vocabulary (and logic) of other knowing praxis, knowledge and belief systems.”1 This is evidenced by the near complete absence of other civilizational languages—Arabic, Mandarin, Hindi, Urdu—from the formation of disciplines and their vocabularies.2 Even within Islamic studies, for example, the term “religion”—impregnated as it is with the Western worldview of “belief system”—is used to denote “din,” rather than using this Arabic term to describe Islam.3 Mignolo and Walsh insist that, in order to truly decolonize learning, we must “change the terms (assumptions, principles, rules) of the conversation and […] dispense with the disciplines, rather than updating the disciplines by ‘including coloniality.’”4

Two takes on this issue—both produced in 1978—claim to provide us with some answers about how to solve this crisis of knowledge. The first is in Edward Said’s celebrated book Orientalism.5 Whilst the critique provided by Said’s concept of Orientalism was groundbreaking, in his book Restating Orientalism, Wael Hallaq points out that Said stopped short.6 Hallaq argues that Said did not probe Orientalism to its epistemological underpinning, satisfied merely with analyzing its economic-materialist aspects, as shown by Evgenia Ilievad.7 In contrast, the second book, Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas’s Islam and Secularism, proposes a comprehensive paradigm shift. Although al-Attas primarily addresses Muslim audiences in light of the crises that have overwhelmed the conditions of contemporary Muslim life, his analysis also provides a useful tool for others to construct their own paradigm of knowledge production. As compared to Said’s preoccupation with “the immediate enemy,”8 al-Attas confronted the “chief enemy” head on. He crystalized the main problem as the problem of knowledge brought about by secularism as a philosophical program by the West.9 In the book Islam and Secularism, he systematically traces the historical genealogy of the Western worldview, defining it and elaborating on its main unifying tenets and the danger to the world it poses.10 Without stopping at merely stating the problem, he proceeds by reformulating the worldview of Islam as a framework to gain an understanding of the problem of knowledge and the construction of a science based upon it, which he went on to elaborate further in his book Prolegomena to The Metaphysics of Islam (1995).11 This process is not a total rejection of ideas that come from the West; it is a process of critically sifting through received concepts from the perspective of attempting to ascertain whether those concepts can be fruitfully incorporated into the Islamic worldview. What this implies is that the aversion of the modern mind to bringing religion into the construction of knowledge is the consequence of influence asserted by the Western worldview.

Islamization of Language

One of al-Attas’s most important theories relates to the Islamic language. In the Islamic tradition, man is defined as “al-hayawan al-natiq,” a language animal. The centrality of language is pervasive within the Islamic sciences, because only through language can human beings reflect reality.12 According to al-Attas, the Islamic language is the “infusion of the basic Islamic vocabulary into the languages of the Muslim peoples.”13 Hence, every Islamic language shares a basic Islamic vocabulary, which is incorporated into a local basic vocabulary. This process started with the Arabic language, which was transformed into a “new” language by the arrival of the Qur’an. The meanings of basic words, such as knowledge (ilm), justice (‘adl), and right action (adab), were transformed and reconfigured to project the worldview of the newly burgeoning Islam.14 Other languages such as Farsi, Urdu, and Ottoman-Turkish underwent the same process of Islamization when they came into contact with Islamic civilization. The adoption of Arabic letters and scripts—with minor adjustments to facilitate the vocalization of particular local sounds—and the influence of Arabic grammar transformed each of these languages, reflecting a new mode of thought.15

In the case of the Malay language, it was already in use as the lingua franca before the advent of Islam, albeit in a limited sense. Being primarily used for trade, the structure of the language is plain and clear. This made it ripe for the process of Islamization, and it “underwent a revolutionary change,” a transformation into a new language known as Jawi.16 As al-Attas noted, “apart from enrichment of a great part of its vocabulary by a large number [of] Arab and Persian words, it became the chief medium for conveying Islam throughout the Archipelago.”17 A plethora of scientific writings were subsequently produced using the Jawi language, covering philosophical mysticism, rational theology, law and jurisprudence, and medicine.18

Jawi as a Language

Jawi is a written language which uses the Malayo-Arabic script in denoting the Malay language.19 The name Jawi originated with the Arabs as an adjective for the people who inhabited the region of the Malay Archipelago.20 As was common among Arabs, the name used for the people of a region was chosen according to the closest major kingdom, which, during the early period of Arabic expansion, was centered on the island of Java. Ibn Battuta, in his travelogue recounting his voyage to the Malay Archipelago, refers to this region as Jawa.21

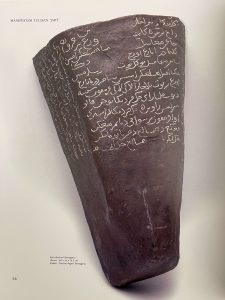

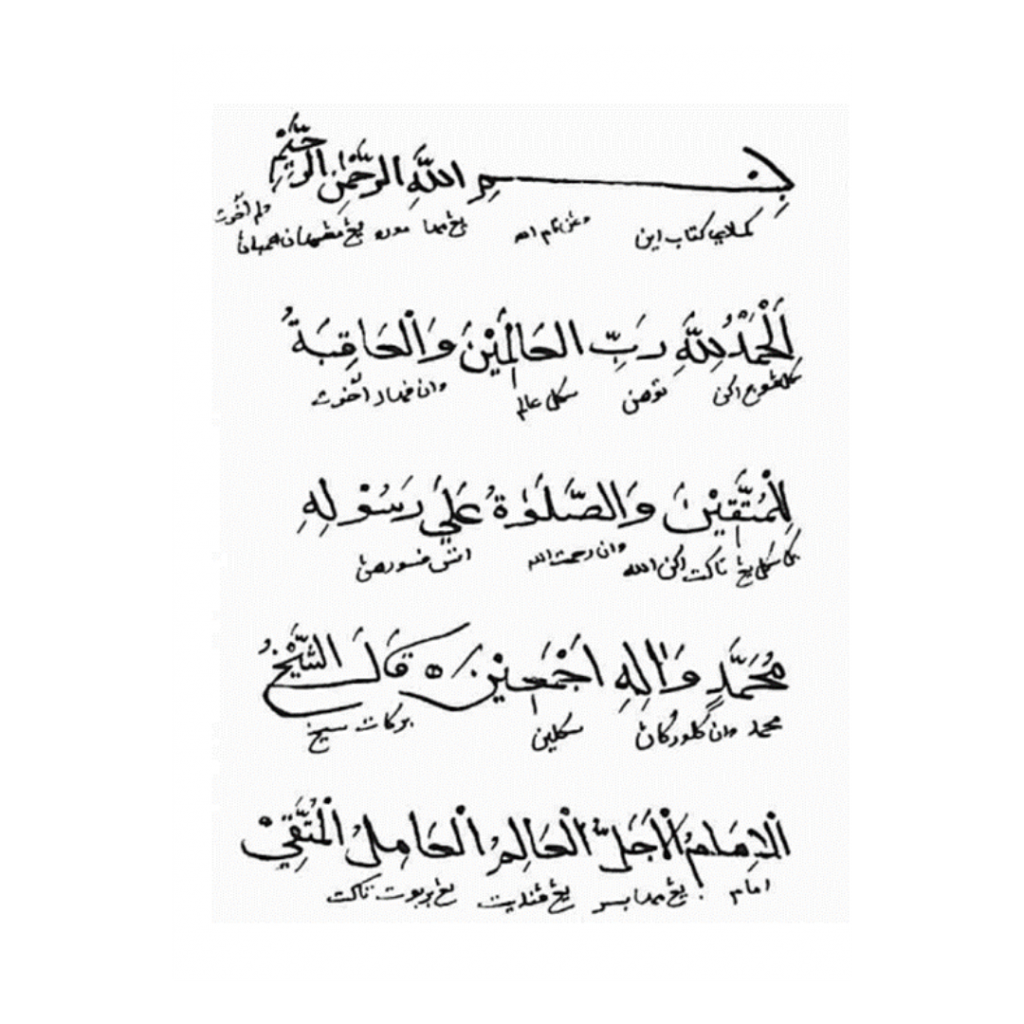

The earliest known instance of written Jawi is the inscription on the Terengganu Stone dating to between 702 and 1303 CE and discovered in Kuala Berang in 1902.22 The earliest known manuscript written in Jawi is a translation of Aqaid al-Nasafi, a treatise on theology dating from around the sixteenth century.23 According to al-Attas, the Jawi language was directly initiated by the Hadhrami Arabs. His arguments are based upon two key pieces of evidence: the naskhi script used in Jawi manuscripts; the construction of five new letters that creatively combine Arabic letters for the vocalization of Malay-specific sounds based on peculiar mode of pronunciation by the Hadhrami Arabs. For example the base letter for letter ‘pa’ (ڤ ) in Jawi comes from the letter ‘fa’ (ف) instead of ‘ba’ (ب ) of the Persian script for the same sound ‘pa’ (پ). Thus, al-Attas concluded, aside from the linguistic evidence, that it is highly improbable that the process of Islamization was initiated by the Muslims from Persia and India.24

Batu Bersurat Terengganu (Inscribed Stone of Terengganu). Source: Dzul Haimi Md. Zain, Malaysia. Jabatan Muzium. Manifestasi Tulisan “Jawi”, Kuala Lumpur, 2006.

Facsimile of the 16th Century Translation of Aqāʼid of Al-Nasafī, Manuscript in Malay. Source: Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Oldest Known Malay Manuscript: A 16th-Century Malay Translation of the ʻAqāʼid of Al-Nasafī, Kuala Lumpur, 1988.

In Malay culture today, however, Jawi is considered a language of lower quality, one that is incapable of truly reflecting the Malay character. Za’ba—Malaysia’s foremost linguist and writer about Malay culture—classified the Malay language into two groups: first is the spoken language, namely the language used by the Malays for daily conversation, which itself also consists of various dialects. The second group is the written language—a formal way of writing the language according to its proper usage. From the second group, he further classified another two sub-groups: colloquial written language and kitab language (the language of religious books). Za’ba criticized the kitab—specifically, the Jawi language—as being overly influenced by the structure of Arabic grammar, so much so as to render the language not recognizable as characteristic of Malay language in general.25

In his introduction to A History of Classical Malay Literature, Richard Winstedt made similar remarks:

[T]he more [the] orthodoxy turned the Malay to later Arabian models, the more debased became his literary style, losing the clear and succinct quality of its own idiom. Metaphysics and law are abstruse for the uncritical mind, even when presented in good translation; they are abracadabra in an imperfect paraphrase.26

These two examples, however, represent a misunderstanding of the Jawi language, which is symptomatic of its having been under-researched and incorrectly theorized as both a tradition and as a body of work. Both scholars have also been influenced in their understanding of Jawi literature by their own preconceived concepts. As pointed out by Vladimir Braginsky:

The theoretical level of the majority of these scholars’ works was fairly low. Among their main flaws, even if it is easily understandable in terms of the scholarship of that time, there was, on the one hand, an obvious exaggeration of the significance of Indian and Arabic borrowings in Malay literature and on the other hand, the evaluation of Malay literature, medieval in its type, in accordance with European aesthetic norms of the nineteenth century.27

Winstedt falls into this category when he remarks:

A detailed review of some of the principal Islamic contributions to Malay literature is necessary to show how wide was the new field opened and at the same time how unscholarly and popular most of the works were and how, apart from the enlargement of vocabulary, they came to exercise on Malay style an influence increasingly bad.28

Despite its clearly outdated nature and its having been superseded by more recent scholarship, Winstedt’s book continues to have echoes and hold a lot of currency in Malay culture. It even continues to hold sway in some academic works in Malaysia, especially works intended for the general public.29

This situation is the result of continued deterioration during the twentieth century, when—in line with the increased popularity of roman script both in publications and as a mode of instruction in the Malay language—Jawi fell further out of favor. The newfound postcolonial independence of several countries during that period also set a different path in the evolution of the Malay language. As each country’s primary aim was to unite its population within the newly established nation-state, molded according to its own nationalist characteristics, the teaching of Jawi in public institutions regressed to include only a highly superficial understanding of proper spellings in the Malayo-Arabic script. Hence, the Jawi language was sidelined and fell into oblivion. As a result, a whole body of knowledge, stored in thousands of Jawi manuscripts, is left unresearched. Even if research was to resume, it would be under an alien framework and using foreign tools, with researchers being led towards incorrect conclusions and unfair judgements.

In his introduction to Abdur-Rahman’s Petuturan Melayu: Kitab Nahu Jawi (The Language of the Malay: Jawi Grammar Book), Syukri Rosli uses the framework laid down by al-Attas to argue that the Jawi language should be studied as a science of language, that is, studied linguistically.30 By putting it into that knowledge context, proper research can be done to appreciate the tradition and do justice to Jawi literature as not merely a second-rate, unscholarly body of work, refuting such claims as those made by Winstedt outlined above.

Akademi Jawi

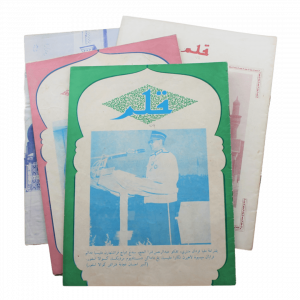

Akademi Jawi is a private institution consisting of cultural workers and researchers that was established by Muhammad Syukri Rosli in 2011. It began as a collaborative project with the Center for Integrated Area Studies (CIAS), Kyoto University, Japan, aiming to romanize all 228 issues of Qalam magazine, a Jawi periodical published in the 1950s and 1960s.31 The magazine was founded by Ahmad Lutfi and was widely read among Muslims in the Malay world. It featured the writing of prominent intellectuals and religious leaders during the period of decolonization, when nation-states were starting to gain independence, and it was circulated throughout the Malay-speaking world, from Singapore to South Thailand, Borneo, and Indonesia. The romanization project lasted for five years, and during those years, Akademi Jawi developed its aim of reviving Jawi language studies by creating a strong educational concept for the Jawi language.

Majalah Qalam (Qalam Magazine) in Jawi language. Source: Akademi Jawi, Malaysia.

Majalah Qalam (Qalam Magazine) in romanized Malay language. Source: Akademi Jawi, Malaysia.

The business currently consists of three main areas that assist in the realization of this aim: a bookstore, a publishing house, and a printing service. In an interview, Syukri Rosli expanded on the need to balance the intellectual aspects of the business with its activism in the field of Jawi language studies.32 To maintain the intellectual project, the business needs to become sustainable. Thus, by operating as a profit-making entity, Akademi Jawi can grow and conduct further research independently, thereby retaining the integrity of their intellectual work.

Another notable project of Akademi Jawi is its collaboration with the Malaysia National Library, digitizing and romanizing forty Jawi manuscripts. To date, this project has also seen the publication of around fifty titles, the majority of which are romanized editions of original Jawi texts.33 Over the course of the project, the complete lack of a professional body able to romanize the substantial body of Jawi manuscripts became stark. And with—according to Braginsky—around 8,000 known Jawi manuscripts,34 Akademi Jawi has the opportunity to become the go-to center for clients and researchers in this field.

Reflecting on the concept of Jawi language studies, Akademi Jawi believes that there are three necessary tenets of analysis for the field: the first aims at understanding the worldview surrounding the emergence of Jawi—the conditions under which it originated and the historical processes that saw it unfold as a language; the second regards studying Jawi as a tradition that reflects the Malay intellectual outlook; and the third uses knowledge of Jawi in order to reconstruct it as a science of language. In his extensive scholarship, al-Attas managed to incorporate all of these elements, the effectiveness of which was shown when he resolved several scholarly deadlocks and clarified many misconceptions in the field of Malay studies. For example, he proved conclusively that Hamzah Fansuri was the originator of the Malay Sha’ir, calculating the correct date of the Terengganu Stone inscription, and he also marshaled arguments for his theory of the Islamization of the Malay-Indonesia Archipelago—these being just two among many achievements.

To replicate this success, Akademi Jawi operates a two-pronged practice. First, doing research and collaborating with institutions of higher education, private researchers, and traditional religious institutions gives Akademi Jawi a wider understanding of the field, thus directing practice in the field and developing it in more efficient and fruitful ways. The second prong aims to engage the masses through publications and education. A unique product of this is the development of the Jawi language teaching syllabus, whereby work in organizing and systematizing this has produced a coherent structure by which to teach the general population about the original tradition of Jawi and to guide academic analysis of the language through the generations. This process of reconstructing the Jawi language syllabus is being carried out with the use of a framework that charts the stages in the process of the region’s Islamization, as proposed by al-Attas. This can help to explain the variations of spellings that appear in manuscripts and inscriptions and, through researching Jawi literature itself, particularly the Kitab tradition, can help in constructing a coherent rule governing the Jawi language which, in turn, can then be used to read and decipher the thousands of available manuscripts.

According to Syukri Rosli, mastering the Jawi language involves a lot more than just learning how to spell Malay language in Malayo-Arabic script , but is a field of language studies in its own right, involving the history, philosophy, and grammar of the Jawi tradition, all of which must be taught concurrently. A lot of confusion arises from the dissemination of misinformed practices in studying Jawi literature, hence the Akademi hopes that there is potential for more positive knowledge to be gained and more discoveries to be made by approaching the field via its traditional framework.

Figure 5: Books published by Akademi Jawi. Source: Akademi Jawi, Malaysia.

To conclude, the field of Jawi language studies has been neglected for decades, and thus little progress has been made. No school in Malaysian universities exists that is dedicated to teaching Jawi as a science of language, unlike other languages such Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, Ottoman-Turkish, Latin, and Hebrew. Akademi Jawi’s vision is to become an independent knowledge institution able to fill this gap, recognized in Malaysia, regionally, and throughout the world in the field of Jawi studies.

Although small in both monetary scale and human resources, Akademi Jawi has made remarkable strides, as can be seen from the company’s production record, publications, research projects, and advances in the dissemination of education in the field. There are, however, some concerns with regards to the sustainability of the project. One of these is that, as a business entity, Akademi Jawi is at the mercy of the market. In order to survive in Malaysia, many publishing houses produce content that serves market tastes instead of setting out to become tastemakers themselves. How Akademi Jawi will preserve its intellectual integrity in the face of such economic challenges remains to be seen, as its proposed approach in the Jawi language studies field remains out of step with mainstream opinions. It is lamentable that as some people in the academic field find the framework of Akademi Jawi to be at odds with what they are used to, they judge it harshly and dismiss it altogether without proper consideration. Nevertheless, the work of Akademi Jawi remains academically rigorous and open to intellectual challenge.

Nazir Harith Fadzilah is the co-founder of Svara, a quarterly literary periodical in Malay language which featured writings on art, culture and society, and the manager of Tintabudi bookshop in Kuala Lumpur. In 2016, he organized the exhibition A Story of Books: Historical Overview of Modern Malaysian Literature during the KL Literary Festival, which explored the history of Malaysian modern literature through publications. In 2018, collaboration with the Malaysia Design Archive, he exhibited a multi-media installation and archival materials titled Anjing [Dog] at Sharjah Art Foundation as part of the research project and exhibition Air Arabia Curator in Residence—A Tripoli Agreement.

Footnotes

1 Walter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, Durham, NC, 2018, p. 113. 1

2 Ibid. 2

3 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Islam: The Concept of Religion and The Foundation of Ethics and Morality, Malaysia, 1976. 3

4

Mignolo and Walsh, On Decoloniality, p. 113. 4

5 Edward W. Said, Orientalism, New York, 1978. 5

6 Wael Hallaq, Restating Orientalism: A Critique of Modern Knowledge, New York, 2018. 6

7 Evgenia Ilieva, “Review: Restating Orientalism: A Critique of Modern Knowledge, by Wael B. Hallaq,” Perspectives on Politics, vol. 17, no. 1 (2019), pp. 245–46. 7

8 Hallaq, Restating Orientalism, p. 15. 8

9 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Islam and Secularism, Kuala Lumpur, 1978, p. 15. 9

10 Ibid. 10

11 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Prolegomena to The Metaphysics of Islam, Kuala Lumpur, 1995. 11

12 Salina binti Ahmad, “Al-Attas on Language and Thought: Its Relation to Worldview, Change and Translation,” TAFHIM: IKIM Journal of Islam and the Contemporary World, vol. 12, no. 2 (Dec 2019), pp. 83–97, here p. 83. 12

13 Al-Attas, Prolegomena to The Metaphysics of Islam, p. 30. 13

14 Ibid., pp. 30–31. 14

15 Al-Attas, Islam and Secularism, pp. 177–79. 15

16 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Preliminary Statement on a General Theory of the Islamization of the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago, Kuala Lumpur, 1969, pp. 23–27; and Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Islam dalam sejarah dan kebudayaan Melayu, Kuala Lumpur, 1972, p. 43. 16

17 Al-Attas, Preliminary Statement, p. 27. 17

18 Ibid. 18

19 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, Historical Fact and Fiction, Johor Bahru, 2011, p. 137. 19

20 Michael Francis Laffan, Islamic Nationhood and Colonial Indonesia, London, 2002, p. 13. 20

21 Ibn Battuta, Travels in Asia and Africa: 1325–1354, ed. and trans. H. A. R. Gibb, London, 1929, p. 273. 21

22 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Correct Date of the Terengganu Inscription, Kuala Lumpur, 1984. 22

23 Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, The Oldest Known Malay Manuscript: A 16th-Century Malay Translation of the ʻAqāʼid of Al-Nasafī, Kuala Lumpur, 1988. 23

24 Al-Attas, Historical Fact and Fiction, pp. 137–41. 24

25 Abdullah Bin Abdur-Rahman and Muhammad Syukri Rosli, Petuturan Melayu: Kitab Nahu Jawi (The Language of the Malay: Jawi Grammar Book), Kuala Lumpur, 2017, pp. 1–2. 25

26 Richard Winstedt, A History of Classical Malay Literature, Oxford, 1977, p. vi. 26

27 Vladimir Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature: A Historical Survey of Genres, Writings, And Literary Views, Leiden, 2004, p. 5. 27

28 Winstedt, A History of Classical Malay Literature, p. 91. 28

29 Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature. 29

30 Abdur-Rahman and Rosli, Petuturan Melayu. 30

31 See the page “About Qalam” on the website of the Jawi Research Society in Japan, http://yama.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp//jawi/eng/qalam/index.html, accessed April 21, 2022. 31

32 Muhammad Syukri Rosli interview with author (Akademi Jawi), London–Kuala Lumpur, March 13, 2022. 32

33 The subjects of the publications include traditional medicine, the Jawi language, theology, religion, and history. 33

34 Braginsky, The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature, p. 1. 34

May 13th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04