Illegalities of Space and Bodies: Exploring the Pedagogy of Sekolah Alternatif

This article is far from able to capture the complicated nuances of the precarious conditions that continue to engulf the Bajau Laut community1—in our context of discussion, this name refers to the scattered ethnic group of the seafaring and maritime community in Sabah, eastern Malaysia. Certainly, confining the discussion of the Bajau Laut within the territorial logic of the nation-state would not do any justice to the community. Justice to them means an interrogation beyond such a logic of the border—where the border historically serves as a site of violence that continues to reproduce the categorization of citizens and non-citizens, where it pursues its objective to segregate those who are deemed civilized or uncivilized, those deprived of civil liberties and rendered undocumented and stateless.

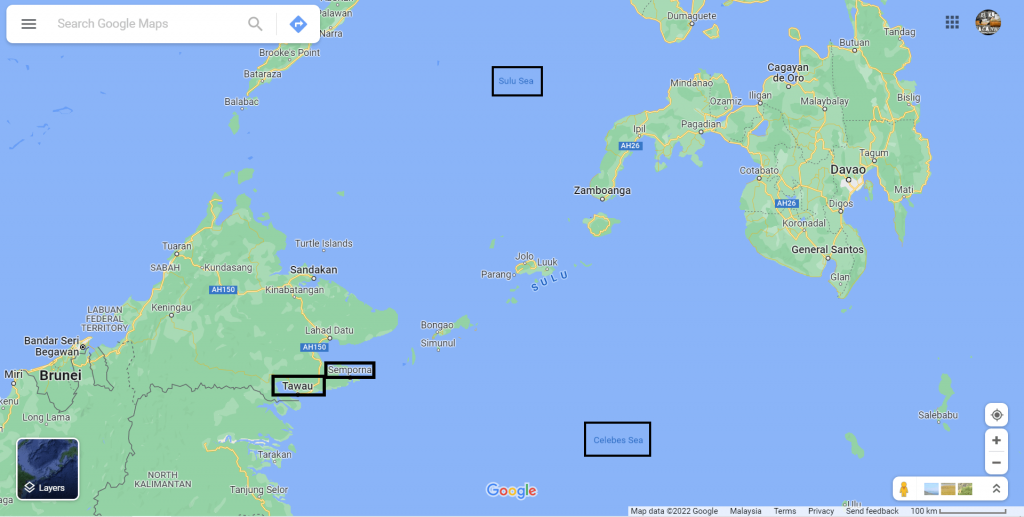

It is within these binaries of borders, that I am going to focus on the ongoing praxis of the Sekolah Alternatif (SA),2 a network of schools working in Semporna, and intermittently in Tawau: both are districts with the highest concentrations of this stateless and undocumented community in Sabah being that they are at the frontier adjacent to the Sulu Sea and Celebes Sea. Central to this objective is to highlight the encounter in space and between bodies within the Bajau Laut community, as well as through the SA’s pedagogy. Indeed, for the Bajau Laut and other “illegal” communities in Malaysia, their vulnerabilities give them near non-existent leverage in negotiating their status in the eyes of the law. Having said that, I would argue that through the SA, there is a continuous action to demand recognition and to a certain extent, equality for non-citizens.

By engaging with the teacher-organizers and the students in the schools in Semporna my intention is to center the communities’ experiences and anecdotes for two reasons. The first is to establish an overview of a longstanding sociohistorical process and the specificity of injustices faced by the community. The second is to provide an understanding of the contemporary context pertaining to the issue of illegality in the community and to show how the SA seeks to negotiate it.

Map of Semporna, Tawau, Sulu Zone. Source: Google Maps.

Movements of Bodies—Transversing of Borders

The map illustrated is fundamental both to outlining our understanding of the geospatial locations of Semporna and Tawau as well as to establishing the interactions of the SA’s schools in both districts, discussed later in this article. Ethnographically speaking, there are four main categorizations of Bajau Laut in Semporna, as highlighted by Ismail Ali, ranging from “Bajau Laut-Darat” (Land Bajau-Laut), “Bajau-Laut Pulau” (Island Bajau-Laut), “Bajau-Laut Laut” (Ocean Bajau-Laut), and last but not least, “Bajau-Laut Terapung” (Wandering/Floating Bajau-Laut).3 It is crucial to note that the school in our context is engaging with the first category of Bajau-Laut which resides in different water villages around Semporna, such as Kampung Bangau-Bangau and Kampung Air Hujung. Meanwhile, the Tawau-based community, located at Kampung Batu 4 in Pangkalan, predominantly comprises the stateless community of Sulu descendants.

Having established some of the facts regarding this diverse stateless and undocumented community and its demography in both locations, it is important to look at how from a historical perspective both the Bajau Laut and Sulu, as boat-dwelling and maritime communities for thousands of years, have been actively moving about in the region and can be traced to various parts of the Sulu Sea, Borneo island, the Celebes Sea, and all the way to the deeper seas of Australia and New Zealand. In one anecdote provided by the Governor of Zamboanga in 1845, as quoted from James Francis Warren (1981) in one of his seminal texts on the Sulu Zone, the Bajau Laut community has been characterized as:

devoted to fishing with no other lodging than their vintas (outrigger boathouses) in which they all live, one family per vinta. They pass years without setting foot on the land except to collect kinding wood […]. The extensive shallows and reefs provide them with an abundance of fish which is practically their only source of food and with which occasionally they can obtain some rice and the scant pieces of cloth they use to cover themselves on especially hot days. Ordinarily, they are naked and fully exposed to the sun and the spray of the sea.4

It is particularly the boat-dwelling characteristic of the Bajau Laut that has ultimately contributed to its being one of the world’s few remaining stateless societies. The community lacks possession of either a territorial base or an internal political structure, in contrast to the nation-state that not only defines their political rights but also their rights to practice their nomadic culture.5 This has aided in the creation of its historically constructed status of social inferiority, in contrast to the Tausog, for example, an ethnic group predominantly located in the Philippines and Malaysia. This is also reflected in the many pejorative terms used to describe the Bajau Laut, such as luwaan (which loosely translates as “that which was spat out”) and pala’u (the negative connotations of which depend on the context of its use).6

The shifting of the Bajau Laut’s geographical location as well as their linguistic multiplicity have also meant that they are identified by different terms in different places, such as Sama Dilaut, Gipsi Laut (meaning sea nomads/sea gypsies), Suku Badjoo, Samal Bajau Laut, Bajak Laut, among other names. Far from being an insular, isolated community, however, it is also pertinent to point out that their seafaring ability and movable allegiance and services have been very much sought-after—during the Sulu sultanates, as the fishermen and gatherers of sea produce, as well as unfortunately being exploited for their surplus labor under the existing capitalist system.7

According to the 2015 Malaysia Population census, there are are approximately 900,000 non-citizens in Sabah alone which are identified by the Malaysian authorities as illegal immigrants from neighboring countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines.8 The number of the population recorded in the census only highlights the intricate flow of human migration in this region, especially in relation to the Bajau Laut and the effects this has had on their legal and political rights. Aside from having been a seafaring community for centuries prior to the formation of nation-states in the archipelago, it is also important to note how the Bangsa Moro conflict in the southern Philippines between 1972 and 1984 contributed to the presence of the Bajau Laut in contemporary Sabah.

Last but not least, the controversial IC Project (Identity Project) undertaken during the premiership of Mahathir Mohamad, Prime Minister of Malaysia in the early 1990s, is also important in understanding the situation affecting the Bajau Laut.9 Through the project, allegedly thousands of people from the Bajau Laut community have received Malaysian citizenships. This was partly for the purposes of shifting the demography and societal character of the Sabah toward the Muslim population, since the Bajau Laut are predominantly Muslim.10 Despite this seemingly “positive” social engineering project, the culmination of these historical events has had a huge effect on contemporary processes of punishment, as well as resulting in the erasure and deprivation of civil liberties and citizenship rights of the many undocumented and stateless community in Sabah.

Negotiating Illegal Space and Bodies: Exploring the Pedagogy of Sekolah Alternatif (SA)

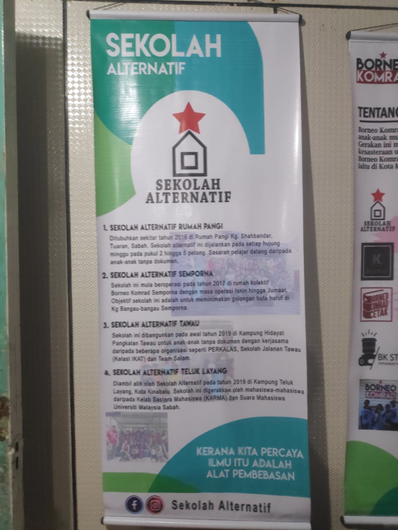

Having briefly set out the patterns of migration and the characteristics that contribute to the Bajau illegal Laut’s status, I would now like to focus on the practices of the SA as a possible site of intervention in reclaiming the rights of citizenship, particularly from the perspective of educational engagement and praxis. Though the SA is the main site of encounter and engagement with the undocumented and stateless community in Sabah—through its brazen manifesto of “education for all”—it is also pertinent to draw attention to its main umbrella organization, Borneo Komrad (BK, which loosely translates as the Comrade of Borneo).

Founded in 2016, the BK comprises multiple networks of entities working within different segments of society with a broad focus, ranging from the student movement and advocacy against urban poverty to cultural engagement in the form of theater-making and literary production. This is particularly significant, as most of its members come from the arts faculty of the local university, Universiti Malaysia Sabah. It is also important to note that the BK operates under multiple entities, including: BK Kraf, a skills-based enterprise that focuses on the stateless community; Borneo Komrad Cetak, the organization’s printing arm that publishes books as well as making silkscreen-printed shirts, among others things; the BK Studio, an entity focusing on photography and video documentation; and lastly, Sekolah Alternatif, their network of alternative schools that aim to eliminate illiteracy among the undocumented and stateless community in Sabah.11 It is from within this particular ecosystem of the BK, and the education-based engagement of SA in particular, that I wish to understand the ongoing struggle faced in the building of, as propagated by the organizer, “an independent and pro-people youth-based movement.”12

Information banners of the Borneo Komrad (BK) and the location of alternative schools organized by them in Sabah. Photograph © Zikri Rahman, 2020.

Coming back to the main topic of illegalities, it is critical to highlight how spaces are occupied by the Bajau Laut community and how their bodies are being perceived as those of the Other—that is, alien bodies—as a result of being stateless. As mentioned briefly before, the community’s traditional space of dwelling is the sea, the islands, and its reefs, and so they are culturally without land ownership. At the same time, the community is very much defined by the border of the nation-state, that is, the Bajau Laut community has become structurally displaced by the logic of the land and its border.

Due to the pressure of assimilation—both socially and economically—the community has been relocated ashore. While many people of the Bajau Laut community are still practicing a semi-nomadic lifestyle, many others are occupying various sites deemed illegal by the state: the marine park, public beaches, and various construction sites scattered around the islands. It is unsurprising to note that the network of the SA itself therefore occupies various “illegal spaces,” for instance in Semporna, a traditional and scattered water village. The SA also operate in various centralized “temporary settlements” that have resulted from displacement over the years. In Tawau, for example, there is a “housing settlement” in which the National Security Council (NSC), the agency in charge of policy implementation for internal security in Malaysia, is heavily represented. Meanwhile, in Kota Kinabalu, the capital city of Sabah, the SA’s school is located in the village set up by squatters next to the university. During my field trip in early 2020, the SA was even visited by the local educational officer who reprimanded the school for having been identified as illegal, demanding it be closed down. Of course, the SA refuses to stop its operations.

With many of the Bajau Laut community involved in the informal economic sector as a result of their undocumented status, they are also vulnerable to arrest, detention, and deportation. As one of the community teachers pointed out, members of the Bajau Laut who were absent from their school community, for example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, was alarming.13 With the authorities applying stricter measures and clamping down on the community, many people have decided to move further into the sea, only occasionally returning to shore when they deem it is safe to do so.

Here, the educational practice of the Sekolah Alternatif has been central to negotiating the Bajau Laut community’s position as illegals in both space and body. I am using the term “negotiate” here, as the SA, and particularly the teachers themselves, are hyper-aware of their own position as both outsiders and insiders within these marginal spaces. Fundamentally, the situation also boils down to the fact that the SA uses visible spaces—particularly around the communal areas where the community practices religious rituals and converge for collective events—to conduct their educational activities. The encounters in such spaces, indeed, influence the way the SA designs its methods of engagement educationally. In being physically present in the space occupied by the community, the SA is strategically in the position to form its cultural and political demands via its educational praxis.

It is also important to note how the teachers and community coordinators of the SA practically live within the community, in order to sustain engagement and to garner, most importantly, the reciprocity and trust that is vital to the ongoing and long-term collaboration between the community and the SA. It is not, therefore, surprising to observe, for example, how several parents have allowed their domestic compounds to be used for class sessions and how some have reached out to share their expertise on fishing or gardening as part of the SA’s learning process.

In relation to this process, one of the community teachers was keen to underscore how the SA’s central concern is to understand the “questions from below” and build the socioeconomic and cultural conditions required by the Bajau Laut in their own space. And a lot can be said for how it has been possible for the SA to recenter and amplify, for example, the languages and culture of the Bajau through their ever-evolving methods of collective learning and articulation.

Of course, it is too early to say exactly how influential the SA are and how successful they will be in collectively asserting the demands for the cultural and educational rights of the Bajau Laut. However, the actively present utilization of education as a cultural tactic within the spaces occupied by the community has highlighted the need for such schemes. Apart from the experimentation with diverse arts and cultural forms such as theater, filmmaking, woodcutting workshops, and urban gardening, central to this process of engagement is the ongoing practice of dialogue fostered by the SA. This has been pivotal in charting the different possibilities of solidarity between undocumented communities and shown powerfully how autonomous, independent sites can exist beyond the state narrative.

Students of Semporna’s Sekolah Alternatif school rehearsing for the play entitled En Route to Independence. Source: Borneo Komrad Facebook page (September 6, 2019), shorturl.at/ipqIM.

The possibilities of such initiatives are endless and manifest in the multiple community explorations carried ou by the SA. Here, I am reminded of the many momentous meetings I witnessed which took place between the school in Semporna and the school in Tawau in November 2019. Though it takes less than two hours to travel the distance between the two schools, the in-person student meetings that took place between the two schools, to discuss and reflect upon anecdotes and their lived experiences of being part of an undocumented and stateless community in Sabah, represented historical moments. Such encounters, as artist-academician Jay Koh has been formulating through his Art-Led Participative Process (ALPP), are fundamental engagement processes positioned to allow “explorative dialogues and participative interactions, recognizing the tensions and anxieties associated with encountering the ‘new’ and communication with others through different social stages.”14 The value of these engagement processes can be seen in the experiences of students in, for example, their open discussion and questions about ethnic rivalry, the normalization of racism, and cultural discrimination.

The unprecedented student meeting that took place between the Sekolah Alternatif schools of Tawau and Semporna. Source: Borneo Komrad Facebook page (November 4, 2019) and (April 18, 2022). Learn more here and here is a video about the filmmaking process.

This process is far from being purely symbolic. Designed to not only provoke the sharing of experience but also the propagation of ideas, it is an initiative rooted in the need to enhance inter-ethnic solidarity between those who are perceived as illegals by the state. And the dialogue is multiplying, with various cultural productions and educational engagements involving the students from the two schools growing, about how to assert their rights to a livelihood and citizenship, via the educational praxis of Sekolah Alternatif.

Zikri Rahman has consistently embarked on collaborations with cultural activist groups in various socio-political projects. Buku Jalanan, a rhizomatic network of street library movement he co-founded, is a loose cultural and knowledge workers movement focusing on decentralizing the modes of knowledge production. He is also affiliated with Pusat Sejarah Rakyat, an independent archival research and documentation platform focusing on Malaysia and Singapore’s people’s history. With LiteraCity, he initiated a literary and cultural mapping project in the city of Kuala Lumpur. Currently pursuing his postgraduate studies in Social Research and Cultural Studies in Taiwan, Zikri Rahman is also a writer, independent researcher, translator, and podcaster for various ephemeral platforms.

Footnotes

1 The paper by Barbara Watson Andaya, “Recording the past of ‘peoples without history’: Southeast Asia’s sea nomads,” Asian Review, vol. 32, no. 1 (2019), pp. 5–33, might be helpful to contextualize the discussion on the Bajau Laut in terms of its social history, see https://www.cseashawaii.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/240175-Article-Text-824986-1-10-20200309.pdf, accessed April 30, 2022. 1

2 See Borneo Komrad’s website, https://borneokomrad.com/sekolah-alternatif/, accessed April 30, 2022. 2

3 Ismail Ali, Komuniti Orang Tanpa Negara (Stateless People) Di Sabah: Kajian Kes Komunjti Balau Laut Dj Pulau Mabul, Semporna, Malaysia, 2010, p. 74, http://docplayer.net/35472016-Komuniti-orang-tanpa-negara-stateless-people-di-sabah-kajian-kes-komuniti-bajau-laut-di-pulau-mabul-semporna.html, accessed April 30, 2022. 3

4 James Francis Warren, The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State, Singapore, 1981, p. 68. 4

5 Ibid. 5

6 Personal communication of Zikri Rahman with a local, October 31, 2019. 6

7 Further discussion can also be found in the brief article by James Francis Warren entitled “Looking Back on ‘The Sulu Zone’: State Formation, Slave Raiding and Ethnic Diversity in Southeast Asia,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 69, no. 1 (1969), pp. 21–33, https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/18248/1/looking_back_the_sulu_zone.pdf, accessed April 30, 2022. See also the seminal text mentioned above by Warren, The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898. 7

8 See population statistics of the Malaysia Census (2015), https://web.archive.org/web/20160212125740/http://pmr.penerangan.gov.my/index.php/info-terkini/19463-unjuran-populasi-penduduk-2015.html, accessed April 30, 2022. 8

9 For further discussion see Kamal Sadiq, “When States Prefer Non-Citizens Over Citizens: Conflict Over Illegal Immigration into Malaysia,” International Studies Quarterly, vol. 49, no. 1 (2005), pp. 101–22,

https://web.archive.org/web/20060226110623/http://www.cri.uci.edu/pdf/ISQ2005FinalCopy.pdf, accessed May 6, 2022. 9

10 Further discussion on this can be found in Carol Warren, Ideology, Identity and Change: The Experience of the Bajau Laut of East-Malaysia, 1969–1975, Townsville, 1983. 10

11 Knowledge-sharing session by Wan Shakila, the school’s manager, January 18, 2020. 11

12 See Borneo Komrad’s website, https://borneokomrad.com/tentang-kami/; and see and also Fig. 1. 12

13 Personal communication of Zikri Rahman with a community teacher, March 15, 2022. 13

14 Jay Koh, “Unpacking the aesthetics of working in public space in Malaysia and Southeast Asia through the lens of art-led Participative Processes,” Third Text, vol. 34, no. 4–5 (2020), p. 10, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2020.1834263, accessed April 30, 2022. 14

May 13th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04