An Elephant in the Room: Farocki’s Take on Song of Ceylon

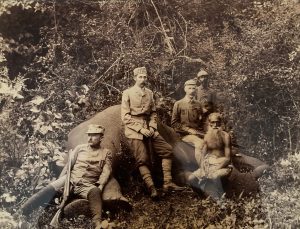

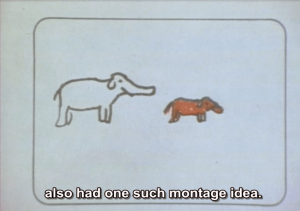

Three images—all European in origin—depicting that decidedly non-European majestic animal, the Asian elephant in its natural habitat of Sri Lanka (Figs. 1, 2, 3). The first two date from a previous era of imperial sovereignty when the sun never set on the British Empire and when Sri Lanka was known as Ceylon. One, a photograph from 1893, is from a series taken to celebrate a successful hunting expedition of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The heir presumptive of the Austro-Hungarian Empire reclines front and center against the corpse of an elephant that presumably he has just slaughtered. The second is a still from Basil Wright’s 1934 film Song of Ceylon. It is taken from a sequence of an elephant and her calf whose cinematic shooting and capture suggest a different sort of trophy. The bounty in this instance is no longer the singular game of individual sport intended for future exhibition and boastful display, but rather one that is motivated by a drive to illustrate and display the natural resources of flora and fauna of the colonies. Like old portrait paintings that included signs of their subject’s wealth, so Wright’s film too is intended to advertise the wealth of colonial possession. Although much has changed in the forty years spanning the two images including rapid modernization, and a “Great War” that reconfigured the European landscape and dismantled the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Ceylon will remain a colony under British rule until 1948. The third image, as we fast forward another four decades comes from a television program made by Harun Farocki on Wright’s film, Über “Song of Ceylon” von Basil Wright (About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright, 1975). In this instance, the elephant and her calf have been translated into a crude drawing rendered by a graphic designer and reshot for television. The drawing is one of a series included by Farocki to punctuate and underscore significant moments in Wright’s work. According to Farocki, they are substitutes for intertitles. As he explains, “There are also small drawings in my film that act as subtitles, which a graphic designer roughly sketched, by the way. The commentary is about them; the film images themselves are not accompanied by a commentary.”1 In 1975, a second world war has ravaged Europe, Ceylon has achieved independence from Britain, and the communications medium is television. The figure of the elephant remains—a touchstone, a trophy brought back to the West through photography, film, and television. Elephants are known for their memory.

Figure 1: Photograph of Archduke Franz Ferdinand with Karl von Adamović after the hunt January 11, 1893. Photograph from the private collection of the author.

When Farocki entered film school in the mid-1960s, regular television broadcasting in West Germany was barely a decade old. As a youth, Farocki’s encounters with television were limited to public-viewing experiences such as watching soccer matches or the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in Westminster Abbey, London. By the 1960s, an increased number of television broadcast systems and a parallel growth in programming corresponded to the increased presence of televisions in households. The new medium was open for development and expansion. In 1966, both the German Film and Television Academy Berlin (DFFB) and the University for Film and Television in Munich were founded. With the energy and imagination invested into the possibilities for the new medium came a streamlining and consolidation of form and style in a process similar to the Institutional Mode of Representation (IMR) that Noël Burch had identified in the first decades of cinema.

Early on in his practice, Farocki turned to television as a source of funding and a platform for distribution. Indeed, one of his first films, Zwei Wege (Two Paths, 1966) was made for the public radio and television service Sender Freies Berlin. The film comprises a meticulous examination and analysis of a large poster decorating the wall of a business in Kreuzberg. However, there is nothing in its form or content that distinguishes it as having been made for television instead of film. Upon graduation from the DFFB, primarily for economic reasons, Farocki turned to television. Film subsidy laws allowed independent filmmakers access to local television networks. Regional networks such as West Deutsche Rundfunk (WDR) provided Farocki with steady employment over the next couple of decades. During this period, he produced over fifty programs. As evidenced from his writings, just as Farocki had meticulously learned the skill of filmmaking, he learned the craft and language of television. Farocki’s programs included interviews with intellectual luminaries like Peter Weiss and Vilém Flusser; focus pieces on a wide variety of topics such as Moderatoren im Fernsehen (Moderators, 1974), or Peter Lorre—Das Doppelte Gesicht (The Double Face of Peter Lorre, 1984); and children’s shows featuring his twin daughters, Einschlafgeschichten (Bedtime Stories, 1976–77) and Katzengeschichten (Stories of Cats, 1978). Additionally, while working for WDR, Farocki made several full-length films sponsored by the network, including his first film Zwischen zwei Kriegen (Between Two Wars, 1978), and Etwas wird sichtbar (Before Your Eyes – Vietnam, 1983). As he recalls, “Throughout the 1970s, WDR was my port of call. WDR was the richest of all the broadcast channels and was always founding new divisions that might have production possibilities. One of these was the division of ‘Media Critique.’”2

Figure 2: Basil Wright, Song of Ceylon, 1934. Source: www.archive.org.

Farocki appreciated television’s role in the public sphere and sought to create critical political programs that not only challenged what they showed but also how they were made. Although television was tightly controlled, some oversights allowed for subversion. As Farocki remembered, “Publicly-owned television was particularly obliging in terms of its negligence,” and he was “lucky to get commissions in a department whose boss was so wrapped up in his career machinations,” that he granted Farocki relative freedom.3 In addition, for much of Farocki’s time at WDR, the commissioning editor, Werner Dütsch, a filmmaker and writer in his own right, supported Farocki’s initiatives to develop alternative programming. Thus, Farocki sought to radically transform the medium and institution of television—working from the inside out as a form of “institutional subversion.” Farocki’s work for television allowed him to engage with media and image production, alter the format of television, push filmic borders and boundaries, and explore new ideas as well as provide a steady source of income both for himself and his crew. As he ironically observes, “Films for television, which I thought I was producing only to make money, were sometimes better than films [I] thought I was making only for their own sake.”4

Beginning in 1973, in a series of written essays and made-for-TV films, Farocki systematically analyzed the burgeoning medium. In particular, he honed in on “features,” the genre of made-for-TV documentaries, which “covers the majority of television journalism and may be compared to focus pieces, essays, reports, and news stories.”5 This genre, made explicitly for television, is not to be confused with documentary or essay films made for theatrical release. Farocki observes that the genre relies on “a certain way of mixing the image and sound information; to market a subject with a minimum of information depth; it covers up its message with a barrage of loveless haphazardly selected images.”6 By manipulating sounds and images, a report is made on a topic about which the public already knows—the exercise is affirmative. A preexistent thesis is constructed out of images and sounds drawn from a vast televisual archive in order to illustrate a story with a foregone conclusion. The selection of sounds and images happens after fixing the script, making images superficial or subordinated to the thesis. Farocki concludes, “One can understand almost all of these programs without seeing the images.”7

In 1973 and 1974, Farocki made two forty-eight-minute programs for WDR 3’s, “Telekritik,” a program that provided a venue where one could talk about television.8 Der Ärger mit den Bildern (The Trouble with Images) and Die Arbeit mit Bildern (The Struggle with Images) constitute audiovisual correlatives that both expand upon and explore similar topics covered in several of his written essays from the time. For his critique of television documentaries, Farocki selected examples that had a progressive message. His aim was corrective and sought to instruct current and future media makers on how to create works that resist a formula of clichéd prepackaged images and sounds as taught in film school. His intended audience is both viewers who consume images and those who make them: “I want to show my critique film to those people who work in television.”9 Reflecting on his methodology in The Trouble with Images, Farocki explains, “When I made my critique of television documentaries for WDF, I cited from the same excerpts several times. It turned out that they were suddenly no longer so ugly because they were now freed from being covered up and could now be perceived for their feelings and thoughts.”10 Farocki bases his method of analysis on a process whereby he breaks down individual components to show how they function as a whole. His hermeneutic approach to interpretation emerges out of the German Romantic tradition whereby each singular fragment at once contains its meaning and that of the whole of which it is part. The whole is contained within the fragment and vice versa. In this instance, Farocki “frees” images from their embeddedness in a montage with other sounds and images that cover up their true nature. Through repetition and extraction, the clips take on a different meaning as they are stripped of the former meanings in which they have been buried. Such an exercise that, with Farocki’s help, produces thought. Farocki restores the value and beauty to images, which in their previous function as banal illustrations have been occluded. Repetition will become a key methodological strategy throughout Farocki’s oeuvre. Thus, in his films, Farocki uses a tactic of repetition where both images and words are repeated sometimes exactly, sometimes with slight variations. This schema is related to director Artavazd Peleshyan’s theory of distance montage, in which certain elements resurface periodically throughout a film. For Farocki, the repetition of quoted phrases pulls them out of the context in which they have been hidden. He explains, “To make phrases stand out as phrases by quoting them, there are simple means, one has to take them out of their context in which they want to hide, and one has to repeat them, expose them to scrutiny.”11

Figure 3: Harun Farocki, About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright, 1975. Source: Harun Farocki GbR.

In addition to direct critiques of the broadcast medium, Farocki directed several shorts on classic films and interviewed contemporary intellectuals. These works apply Farocki’s critical dictum to make “work better.” Farocki was editor of the journal Filmkritik at the time, contributing regular film commentary. These filmic shorts are in part a response to Farocki’s overall dissatisfaction with contemporary books on film. He points to the deficiency of this genre in Filmbücher (Filmbooks, 1986). In this short, Farocki poses as a reporter sitting at a desk reviewing several contemporary books on various cinematic subjects, including Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle, Wim Wenders’s King of the Road, Pauline Kael’s study of Orson Welles, and Herman G. Weinberg’s biography of Erich von Stroheim, and many others. He faults each example for a particular lack. These lacks are often related to the use of illustrative images by their authors. Sometimes, the quality of the reproduced photographs falls short; in others, it is the cropping for publication which focuses on individuals and faces at the expense of backgrounds that is the problem. In yet others, it is the use of photographs taken by set photographers during production rather than actual film stills that Farocki finds misleading. In more egregious examples, photographs may be mislabeled, unrelated to the main text. Farocki’s critique extends to the content of the text, especially with autobiographical works that recall production processes and provide “indiscrete details” about romances on set but remain silent on matters that count, such as finances. In one case, Farocki points out that the publicist for the film is the book’s author and producer, making it part of promotional strategies. Why, he muses, should a reader pay ten marks for an advertisement? But what are the alternatives to written film criticism? Might it be possible to perform analysis through a dynamic audiovisual medium instead of relying on static words and images?

Between 1974 and 1987, Farocki offers, as an alternative to popular film books, eight television programs that sought to cater to a mass audience interested in cinema. The first of these, Über “Gelegenheitsarbeit einer Sklavin” (About “Part-time Work of a Female Slave,” 1974), focuses on Alexander Kluge’s eponymous 1973 film. Unfortunately, the film was never broadcast. This was followed by About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright (1975), in which Farocki introduces various concepts of film history and techniques developed by Wright and John Grierson’s GPO team. Filmed on location in Sri Lanka, Song of Ceylon (1934) is an extraordinary early travelogue essay film that depicts, through a series of disjointed tableaus, life in the former colony. The soundtrack was composed and designed in London by the GPO team including Walter Leigh, a student of Alberto Cavalcanti and Paul Hindemith. Song of Ceylon was funded by the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board, and the infrastructure of colonialism imaged through the lens of the tea industry is conveyed as an integral part of Sinhalese culture rather than as an alien disruptive force. Farocki’s short opens with a crudely drawn image of a television set, reminiscent of the one in The Trouble with Images, with the handwritten words: “Telekritik zu” and Farocki’s voice announcing, “We are going to examine films, in order to learn something for today’s television. For watching television and for creating television.”12 Farocki’s pedagogical tone bares his belief in the potential of television as an instrument for instruction. He announces, “We will make you aware of a few cinematic methods, and we will look at the results of a few cinematic methods.” Parallel to Bertolt Brecht’s “Lehrstücke” (Learning plays), Farocki produces what might be referred to as “Learning television.” This form, a precursor to distance learning, consists of a medium programmed for education and instruction instead of entertainment. Seemingly riffing on “Fernsehen,” literally to see faraway, Farocki opens his discussion with an explanation of “primitive” travel films that brought images and pictures back home. Farocki’s program is composed of sequences from the film interspersed with illustrative watercolor paintings similar to those in a journey’s logbook or a filmmaker’s storyboard. It is one of these that the elephant and calf come from. Farocki reminds the viewer, “When you took a trip every picture you brought back was valuable.” Even more valuable were films that, unlike still photographs or drawings, could transmit movement. One of the first features of Song of Ceylon that Farocki stresses are shots of people in motion, and their internal rhythms connected to nature. Footage of swaying trees and palm fronds is intercut with clips of people going about their everyday activities. As Farocki notes, the people are connected in this community; their shared movements bring them together. The “shared” moments extend to animals and nature. The sketch of the elephant and child introduces a sequence by Wright in which a mother elephant washing her baby is followed by that of a Sinhalese woman washing her naked infant. Wright suggests a parallel of maternal caring that extends from beast to human.

Farocki digresses from his moving picture lecture on Song of Ceylon to focus on Sergei Eisenstein’s ¡Que viva México! (1931). Farocki replays a scene from Eisenstein’s film in which, through the dense foliage, a young woman’s partially obscured face gradually becomes recognizable. He explains that Eisenstein used a mirror to reflect light off the girl’s face. What appears as a natural interplay of sun and shadows is an artificially produced cinematic effect. The cutaway to Eisenstein may not have been coincidental, for Basil Wright had taken a course on film aesthetics and montage with Eisenstein and followed his tutor’s dictum “Go the way the material calls you […] the scenario changes on location and the location shots change in the montage.”13

Song of Ceylon is divided into four unrelated chapters that promise to show and tell “two or three things” (in this formulation, Farocki nods to Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, 1967) instead of attempting to depict a totality. Farocki underscores, “And when you show a few particulars in detail, an idea of a whole might emerge.” Following Wright’s lead, Farocki “too will only show a few details of the film Song of Ceylon.” He identifies how Wright and his team bring together several types of images, each of which is made differently. There are those fabricated in the film studio, such as images of foliage, in which the “forests of the past look so synthetic—they are a reconstruction.” This observation proleptically connects to one of Farocki’s last works, Parallele (Parallel, 2014), a four-channel installation that traces a genealogy of artificially generated images and, in particular, trees. Second, there is the footage filmed on location that is documentary and less prone to manipulation. Third, there are symbolic images like a giant Buddha or a religious temple that find their place in Wright’s film, as do micro-narrative sequences filmed with multiple cameras. Finally, there are scenes staged and performed explicitly for the filmmakers such as one of young local dancers performing for a colonial landowner. These different images are woven together by Wright and his team and organized into constellations of meaning. Farocki pulls each one out of its embeddedness and analyzes it for its individual properties before reinserting it within his film’s continuum.

Two interrelated characteristics of the film stand out for Farocki: movement and sound. Movement is inherently related to sound, for, unlike an image that can be stilled, sound travels in waves and requires motion to exist. Farocki imparts that one of the most remarkable aspects of Song of Ceylon was its elaborate post-production sound design. Besides pointing out the various ways that Wright adds music and sounds to the images to create a flow and higher degree of realism, Farocki isolates a couple of sequences that encompass the production’s overall musical structure, generating its “song.” Images are scored and arranged in the film the way notes are placed in a musical composition, leading Farocki to refer to it as “a music of images.” Halfway through, Farocki inserts the intertitle “Song,” followed by “A film like a song, a film like music.” His commentary continues, “The subject crystals that are generated for an instant and then disintegrate again. To make music from images, there are dissolves. Dissolves match the pictures to each other, make them smooth, allow for disparate things to come together.” Farocki illustrates his observation by replaying a series of dissolves taken from Wright’s work. He stresses the importance of rhythm and motion as a structuring device as illustrated by the extraordinary opening sequence of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, 1927). Farocki introduces Ruttmann as part of a movement in the 1920s that treated images and pictures according to their laws. He explains that they were edited not according to a preconceived plot or narrative that was imposed on them but rather one that emerges from the images according to their properties. Ruttmann used a rapid montage of images to impart the effect of travel, the speed of modernity, and the vibrancy of life in an urban center. Farocki refers to this process as a “montage idea,” but is quick to undercut his praise of Berlin: Symphony of a Great City with the overall assessment that for Ruttmann the result is a “trivial philosophical idea that is a pretext for a montage of ideas.”

A post-production team in London created the formal musical structure of The Song of Ceylon. The sound design is composed of non-diegetic music, Foley sounds of nature, and other background noises. Farocki pauses over one sequence in Song of Ceylon, “Commerce,” and replays it several times. The scene shows a young man scaling a coconut tree and reaping ripe coconuts. Once the nuts fall to the ground, the man gathers them, splits them in half, and extracts the fruit. Other villagers are involved in harvesting, processing, and storing grain. Farocki observes, “These different kinds of work stand side by side, in order to show the simultaneity and detachment of different work relationships in Ceylon. There is, however, a limit to these cinematic methods. You can’t tell from the look of the work, whether its goal and speed were specified by the commercial director. You can’t simply distinguish by looking at the difference between the commercial and the working village community.” Farocki replays the sequence. This time he is almost silent, and the original soundtrack resonates, filling the volume. Against the rural preindustrial imagery, disjunctive non-diegetic sounds emit broadcast noises of modernity. Recorded voices utter phrases, information bites are traded, and an acoustic stage ushers forth the voice of the colonizer from afar as it is transmitted through telephones, radio broadcasts, and announced recordings. Anonymous speakers provide statistics about stocks and trading, transportation, and commerce. There is discordance between what is seen on the screen and what is heard on the soundtrack. A sound bridge that spans time and space connects images of old work with sonic new ones powered by commerce and colonization.

Figure 4: Harun Farocki, About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright, 1975. Source: Harun Farocki GbR.

Throughout About “Song of Ceylon,” Farocki returns to the musicality of the composition. He observes that Wright focuses on small movements that are only detected through “a patient observation.” A recurring image of a fisherman pulling his net out of the water with a measured gesture and rhythmically folding it to prepare for the next cast-off prompts Farocki to ask: “How is melody created?” He responds, “He [Wright] tried to find the melody in the material not the other way around, using music to make the material dance.” Farocki replays the sequence. This time, however, he adds the images directly proceeding and preceding it, situating the sequence in a larger filmic continuum. We see a young man sitting by the water, a fisherman, and a man pounding laundry. These individuals’ movements rhyme with each other and harmoniously unite their separate activities. Wright achieves what Farocki strives for in his television critiques: “not any idea that was built into the material but rather an idea that was found in the material.” In the last section, “Learning for TV (4–00),” Farocki explains that Song of Ceylon prioritizes images and their placement within the totality of a film. He stresses, “What we must particularly demand of an image is that you can tell from looking at each image what it is, and what it represents. And not just what it is, and not just what it represents. An image, of which you can tell by seeing it from whence it was taken and why it is now there.”

Figure 5: Harun Farocki, About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright, 1975. Source: Harun Farocki GbR.

Here is another elephant from Wright’s film, which Farocki selects for his analysis: it is a seemingly playful sequence chosen for its artful manipulation of sound and images (Fig. 4). Music from an oboe-like instrument is graphically matched by the post-production team to an elephant, making it seem like the majestic creature is speaking. Thus, careful employment of sound imbues the power of speech to a mute animal, anthropomorphizing it. Riding on the back of Wright’s elephant is a man with a long crop used to whip the beast into obedience much like the colonial subject (Fig. 5). What the elephant “sings” is left untranslated and one is reminded of Chris Marker’s SLON Tango (1993) of the lone elephant “dancing” a tango after it has been deserted in a Sarajevo zoo during that horrific war. Elephants remember and bear witness (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Chris Marker, Slon Tango, 1993. Source: Les Films du Jeudi.

For Farocki, each image is significant; it is never a filler or placeholder. At the film’s end, he writes, “No final word. A final picture.” A watercolor of feet standing in water cinematically dissolves into the beginning sequence from Song of Ceylon of a shot of a young man’s feet in the lagoon. The camera slowly pans up to reveal the man’s body and upward tilted face. The camera follows his gaze as he looks toward the mountains. Farocki repeats for the fourth time in the short a sequence of the mountain and Wright’s commentary announcing: “This was a high mountain to worship.” But what was that high mountain which was to be worshipped and that Farocki underscores by replaying this sequence four times? The image of the mountain suggests both the sublime and nature—Farocki’s final words are “This is what one must demand of an image—that in each image one can see what it is, and what it represents”—a mountain that is worshipped as a deity which represents the wholeness and integrity of nature. But to continue, following Farocki’s instruction, an image must also always show “whence it was taken, and why it is there now.” And here in this instance, there are silences surrounding the images—those in Wright’s original film, namely the other side of the history of colonialism—those images of abuse, domination, cruelty, subjugation—a history to which Farocki does not allude or mention. Indeed, by the mid-1970s when Farocki made About “Song of Ceylon,” his silence is striking. He selects Wright’s film for its formal properties—its innovations in sound, movement, and montage—whence it came from and why it is here are not questioned.

Screening the film today, the silence resounds and reverberates with the 1893 photograph commemorating the elephant shoot. Perhaps that mute and silent image vocalizes more loudly the colonial infrastructure and systemic brutality than either version of Song of Ceylon. The Archduke is placed in the center of the image, to his right, positioned slightly lower resting on the elephant’s rear flank with a very large hunting rifle pointing upwards between his thighs, is an Austro-Hungarian Admiral Karl von Adamovic. Adamovic, at the time, commanding the S.S. Fasana, was en route around the globe as part of a lengthy seafaring scientific expedition. The ship had made stops in Australia, Japan, Burma, Indonesia, New Guinea, Fiji, and other “exotic” and “oriental” locales. At each port of call, they laid anchor and stayed a few days studying “locals,” recording their customs and rituals, photographing the subjects and their environments, and taking specimens of flora and fauna for transportation back to the Austro-Hungarian empire for further study. It was then only natural that when the paths of the Archduke and his admiral crossed, they would engage in the aristocratic entertainment of a hunting expedition. Adamovic’s posture and the size and prominence of his weapon suggest that perhaps he fired the lethal shot that felled the majestic beast. To the left of the Archduke, at a slightly lower angle, but also with a rifle, is the British officer in charge who would have organized the expedition. Behind him, in the shadows of the foliage, is the Sinhalese liaison who had made further arrangements, serving as a conduit between the foreign hunters and the “native” offerings. In the foreground of the photograph, posed sitting on the elephant’s front legs, is an indigenous person naked except for a loincloth. He is the scout who led them to their trophy. An inspection of the elephant reveals that it didn’t even have the prized tusks; in short, the kill yielded no trophy but the sport and the photograph! One is reminded of a citation from John Akomfrah’s three-channel video installation Vertigo Sea (2015) “the ways of killing man and beast are the same.”

The elephants shot by Wright’s cameras are left to live and are filmed by the camera crew who are seemingly in awe and wonder. They are at one with nature and linked to the colonized subjects as both sequences demonstrate. What is not shown is that, like the indigenous population of Ceylon, they elephants are part of the enslaved labor force; made to clear forests and perform other duties vital to construction and modernization. Wright’s film renders this domination invisible. In contrast, Farocki makes visible the labor of the people, their rhyming movements, and the invading presence of modernity, which accelerates work and emphasizes productivity. The elephant’s subjugation, however, is ignored. Farocki includes the shots of the animals as a display or attraction; a cinematic equivalent of a zoo. For Farocki, there is a clear distinction between humans and animals. Animals rarely appear in his films and when they do, they are props, and curiosities. By including the two sequences of elephants from Song of Ceylon in his television lesson, Farocki reinscribes them into a system whereby the beasts are just that: beasts. Cinematic moments to elicit a pause for spectators to enjoy the “exotic” view. A final image (Fig. 7), from March 2022, a zookeeper in Kyiv comforts a distressed elephant in a state of high anxiety due to the bomb that has just landed. The smaller animals, including the big cats and the apes, have been transported to Poland; the large ones, like the giraffes and the elephant remain, to meet their fate. The ways of killing humans and beasts are the same.

Nora M. Alter is a Professor of Film and Media Arts and the author of Vietnam Protest Theatre: The Television War on Stage (1996), Projecting History: Non-Fiction German Film (2002), Chris Marker (2006), The Essay Film After Fact and Fiction (2018), co-editor with L. Koepnick of Sound Matters: Essays on the Acoustics of Modern German Culture (2004), and co-editor with T. Corrigan, Essays on the Essay Film (2017). She is completing a new book on Harun Farocki.

Footnotes

1 “In meinem Film gibt es außerdem die kleinen Zeichnungen als Zwischentitel, die habe ich – von einer Grafikerin übrigens – hinkritzeln lassen. Auf ihnen liegt der Kommentar, die Filmbilder selbst werden nicht von einem Kommentar begleitet.” Unpublished conversation between Harun Farocki, Michael Baute, and Stefan Pethke on October 10, 2008. I am grateful to Volker Pantenburg for this reference. 1

2 Harun Farocki. Zehn, zwanzig, dreißig, vierzig. Fragment einer Autobiographie, vol. 1, Writings vol. 1 Berlin, 2017, p. 159. 2

3 Harun Farocki, “A Magical Imitation of Reality,” in Joanna Fiduccia (ed.), A Magical Imitation of Reality: Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl, Book 2, Milan, 2011, p. 7. 3

4 Harun Farocki et al., Harun Farocki: Another Kind of Empathy, Cologne [1991] 2016, dust jacket blurb. 4

5 “ist die mittlere und große Form des TV-Journalismus, mit Aufsatz, Essay oder der Reportage im Wortjournalismus zu vergleichen.” See Harun Farocki, “Drückebergerei vor der Wirklichkeit. Das Fernsehfeature/Der Ärger mit den Bildern,” Frankfurter Rundschau, no. 127 (June 2, 1973); reprinted in Volker Pantenburg (ed.), Harun Farocki. Meine Nächter mit den Linken. Texte 1964–1975 (My Nights with the Leftists), vol. 3, Cologne, 2018, p. 132. 5

6 “Feature bezeichnet eine bestimmte Art, Bild-und Ton-Informationen zu verwursten; mit Minimum an Informationstiefe ein Sujet zu vermarkten; mit einem Schwall von Halbheiten lieblos aufgenommene Bilder zuzudecken.” Ibid. 6

7 “Fast alle Features kann man auch verstehen, wenn man die Bilder nicht sieht.” Ibid., p. 138. 7

8 “man kann dort im Fernsehen über das Fernsehen sprechen.” Ibid., p. 132. 8

9 “Ich will meine Kritikfilme den Leuten, die im Fernsehen arbeiten, vorführen.” Ibid., p. 139. 9

10 “Als ich im WDF die Kritik über Features machte, zitierte ich manche Ausschnitte mehrfach. Es zeigte sich, daß sie auf einmal nicht mehr so häßlich waren, weil sie jetzt aus dem schlechten Vertuschungszusammenhang befreit, der Wahrnehmung in Gefühl und Gedanken zugänglich wurden.” Ibid. 10

11 “Durch Zitieren Phrasen als Phrasen herauszustellen, gibt es einfache Mittel, man muß sie aus ihrem Zusammenhang holen, in dem sie sich verstecken wollen, und man muß sie wiederholen, also der Überprüfung aussetzen.” See Harun Farocki, “Über die Arbeit mit Bildern im Fernsehen,” Filmkritik, vol. 211, no. 7 (1974), pp. 308–16; reprinted in Pantenburg (ed.), Harun Farocki. Meine Nächter mit den Linken. Texte 1964–1975, p. 167. 11

12 Über “Song of Ceylon” von Basil Wright (About “Song of Ceylon” by Basil Wright), screenplay/dir. by Harun Farocki, Germany, 1975, 25 mins. All the following quotes are from the film unless referenced otherwise. 12

13 As cited by Jon Hoare, “Song of Ceylon,” in the booklet accompanying the DVD box set Addressing the Nation: The GPO Film Unit Collection, vol. 1, London, 2008, pp. 44–45, here p. 44. 13

May 13th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 04