How Film-Making Can Contribute to a Collective Consciousness Against War

As a witness of the war in my home country, Ukraine, and an artist / filmmaker, who now knows what war is from the inside, I had an inner urge to gather the thoughts that were in my head over these weeks that changed my life, in order to heal and to remind myself of my place. I framed my article around the notion of collective consciousness with regard to finding a common social ground, values, imaginary and stories that can create the base of future development of human thought and psyche against war. The main focus is on the ways film-making can contribute to such development and to the directions it can take in war times, as I truly believe in the great opportunities that film-making provides us with to shape the collective consciousness and to make the world a better, more equal and peaceful place. This potential is based in the nature of film-making itself. In this article, I want to highlight just a few dimensions of it.

Film as dialogue

I believe that people do not just “want to make films”, they want to say something, as art itself is also always a dialogue—with oneself, with other people, and also with different generations across time and history. I like the quote by Hayao Miyazaki “You have to be determined to change the world with your film, even though nothing changes”. When I taught an art film course for children, I used to repeat this phrase, stressing that film-making actually changes something. If the film reaches at least one person, or one hundred, or one million people, makes them feel, rethink towards a more conscious spiritual path—it’s already worth making a film.

To make a film is to tell a story

We live with, through and by stories. We make stories alive, and they keep us alive, it’s a two-way process. For example, I can tell you a story of my French teacher: during the first week of war she got stuck in her own house in a village near Kiev, where the Russian occupiers would kill innocent people, they would run into their homes and mock them, making them kneel and ask for mercy. She managed to get to a safer place after running for days through the forest, as the road was blocked. When she finally managed to escape , she invited us to continue classes, as she knew the emotional importance of getting something back from our prior lives. This can become a story of endurance, of persistence, of love for life—this can be the starting point for a film, and now each Ukrainian has a story worth making a film.

Some stories make us grow and become better people, do what we thought to be impossible. Other ones make us kill and destroy. What happens now in Russia is a domination of the second kind of story. And film-making, in my opinion, provides endless opportunities for telling the stories that are worth telling, and for reaching people with them.

Film as response to the human need for guiding points

We struggle to admit that in this world we are rather like lost kids in the big shopping mall than the members of the superior species that rules over nature. We search for the ways not to feel alone in this world, to relate to something bigger than ourselves, in everything we do—politics, religions, even wars. We need guiding points, values and ideals for living, and we are always seeking a sense of our life to live. Art is another great way to make sense and reach beyond ourselves. In this case, by art I mean modes of creation that are about searching for a deeper and more conscious life, for comprehending the world: inner and outer. On this instance, artists can be seen as guides that strive to reach deeper levels of existence, give their variations of responses to eternal human’s questions and show them to society. These are our ways to contribute to a collective consciousness, to create the exchange of wisdom and knowledge between generations and within history, and to guide people through the necessary inner transitions, from moments of uncertainty to moments of clarity, helping to overcome struggles, showing what to leave behind and what to give space for. That is how art becomes a bridge between reflection, action, and prevision. I consider it important for us, film-makers, to understand and take responsibility for it in our practise.

Film-making as art and as unity of all arts

Now video is everywhere—it is the medium for commercial communication as well as a form of entertainment. Its social, spiritual, and psychological functions however are mostly neglected. Film-making is the unique form of art that by nature unites in itself two essential factors for a global change: (1) film-making is the unity of many people while creating a film, it enables them to become involved and transformed in the process (2) film-making is the unity of all arts. A friend of mine once said: as cinema unites all kinds of art, perhaps it has the power to unite all nations.

Artistic truth

I believe that film communicates with the audience through truth and trust. When I began to see all films as real-life-based, no matter if they have been written as “based on real story” or not, it changed my whole perception. The point is that at the core of each film is the psychological truth that then gets artistically transformed—a human’s real-life experience base that creates the depth to which people can relate, otherwise it just doesn’t work and the audience can never be fooled. In a way, each film is a sort of statement: “I believe that life is like that”, at that point in time for its maker, who needs to take full moral responsibility for it. For me, film-making is the main motivation to become a better, healthier person. I’m always motivated by asking: How can I communicate with many people through my films, if I’m not ready to do the right thing or to say the right thing to one person, even to myself, in my life?

Film-making in times of war

To some extent, art can be outside of politics, but it cannot be outside of war—this is the position I relate to as a person who lives through wartime. I know that everything that I will create in the next few years in some way will relate to war, or will be perceived as such, whether I intend it or not. Creating something unrelated to war will also be a choice of not facing it or imagining the life without it. War puts a mark on us deep inside, and it does the same with our works.

For example, during the last peaceful evening with the children I was teaching—ten hours before the war started—we made a video about friendship, based on acceptance and respect for the difference of another person. While editing it, I realized how relevant it is now, as we are dealing with the aggression from the country that would never accept our independence, history, culture, values, and path. Everything that was before feels surreal, but it will always be essential. We had friendship, we had love and we had art. And we will embrace it, make it stronger, as now we know the value of it. This is how this simple video made by children became a statement under war conditions.

Collective (un)consciousness

Cinema is a frame on the reality that enhances and embraces the parts it chooses to be on the screen. And so does war: it makes characters appear on the border, all the beautiful and ugly sides pushed to their limits. In the dark times we feel everything subconscious, metaphorical and deep stronger than usual. And the line between real and surreal, possible and impossible, becomes almost invisible. In our turbulent times, the film world will have an important mission, many things will be rethought, in particular through the change of values. I believe that the big importance should be given to the inner world of war: what in us, humans, provokes us to repeat the same circles of creation and destruction, what makes us choose to destroy and to kill? As all wars have a common nature and similar development , I believe that change can come only from within: we need to have a deep understanding of both wars and humans psychologically, and especially the unconscious parts of our psyche, as well as we need to learn our lessons from the history.

It’s a lot to process what one’s psyche is going through during the war, what we feel, and how we think. When the war started, I began collecting the dreams of Ukrainians. Through dreams, motifs, and symbols that repeat, I see not only the reflection of inner world of individuals but also of the new history of the nation. Therefore, I am searching for connections between the war and the inner self.

“It’s like in a film”

When we undergo very stressful and unimaginable situations, we get a feeling that it is like in a movie; what is then left for film-making in times when our reality becomes a film we would never wish to watch?

I heard the phrase ‘it is like in a film’ from almost every friend I talked to during the first week of war, I got this feeling myself—the entire first day of war I lived as if I was in a film, imagining myself on the screen, trying to remember what the film characters do in such circumstances. It is especially relevant for young generations, because we are used to watching shocking content and cruelty on TV and in cinema, and when facing it in real life, we feel the absence of the screen. Nowadays wars are influenced by technology, and the information is perceived as weapon. Each second we know what happened and where because of witnesses filming and taking pictures and people on social media sharing them—reality now documents itself faster than ever. People, who did not go through war themselves, again see it through the screen.

So, what is left for film-making in times when our reality becomes a film we would never wish to watch? In some way, the answer to this question I am searching now, working on my next short film during the residency at Harun Farocki Institut.

Film-making and global empathy

On the global level, I believe that change can come only from within and is directly connected to the development of empathy. From the beginning of human’s existence we can see its gradual development: from an empathy to one’s closest person, one’s tribe, one’s settlement, one’s country—towards its globalization. It is influenced by many

factors: the experience of a world war being one of them, but also the development of technology, the increase of traveling and migration, and global access to news, art and films. However, technology and science are developing faster than human’s psyche, therefore they can’t be perceived as ends, but only as means that can be used for the good or for the bad, for creation or for destruction. I believe that when we develop global empathy, based on understanding of us being all equal humans prior to nationality and so on, the wars will stop.

On a personal level, people who have gone through a war feel a wall between themselves and others, for whom war is something from the news. I think that these walls can be broken only by way of empathy, and I see an important mission of film-making (and art in general) in the contribution to the development of global and personal empathy.

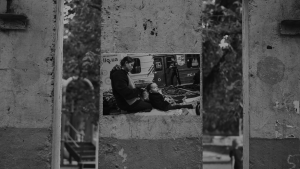

The images accompanying this text have been taken from the short film Between before and after /war/, made by Marichka Lukianchuk in March 2022 in response to the war, using footage from a video by herself and Elena Baronnikova shot in 2020, yet not finalized at the time.

Marichka Lukianchuk is a visual artist and a film-maker from Ukraine who also works collaboratively. In 2021 she graduated from Interdisciplinary Arts studies at Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands. Her short films Past Future Mountain and Spiderweb for Shelter and Hunt were featured in international film festivals. Lukianchuk is currently holding a residency at Harun Farocki Institut, facilitated with the support of Artists at Risk.

April 14th, 2022 — Rosa Mercedes / 05