School of Communications, Department of Radio, Television and Film, Howard University

As can be understood from the conversation between Shirikiana Aina Gerima and Haile Gerima, Skip Norman must have come to Howard University in Washington, DC after his return from Germany, at a time when Gerima had already started teaching in the Department of Radio, Television and Film at Howard’s School of Communications in 1976. Howard University is considered one of the preeminent Black academic institutions in the United States, “the capstone of Negro education” since its foundation in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, in 1867. It is named after its founder, the white general Oliver Otis Howard, also the Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau at the time. Through the work of Africanist scholar and collector Alain Locke, which attracted the likes of Zora Neale Hurston, who studied at Howard between 1918 and 1924, the university gained a reputation as one of the centers of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and ’30s. Subsequently, the campus became a hotbed of the Civil Rights Movement and student activism from the early 1940s and into the ‘60s.

In 1971, the School of Communications was opened. Comprising various broadcast facilities—a United Press International (UPI) teletype service, a Speech and Hearing Clinic, an electronic writing laboratory, a student-operated radio station (WHBC), and the first Black-owned and operated television station (WHMM-TV 32)—it was composed of the departments of Communication Arts and Sciences, Journalism, and, finally, Radio, Television and Film—the place where Gerima and other Black filmmakers such as Alonzo Crawford and Abiyi Ford taught. In Howard’s yearbook The Bison: 1979, Gerima is quoted as saying, “We must not be spectators of our own struggle nor must we be the victims or casualty of history, but we must assert in making and writing our own history; for a history paternalistically given, donated or made by others, does not guarantee or insure our true human existence.”

In 1978, while Skip Norman was one of the two cinematographers (together with Norma Jean Bialock) working on Gerima’s 128-minute-long, but hardly known documentary Wilmington 10 – U.S.A. 10,000—on the case of nine Black men and one white woman convicted of firebombing a grocery store in Wilmington, North Carolina—he also began teaching at Howard. Although traces of his teaching activity, while fondly remembered by the Gerimas are scarce, if not missing altogether, in all likelihood Norman held mostly practical classes at undergraduate level at the department.

Around 1978, another Ethiopian filmmaker, Abiyi Ford (who died in 2018), started to teach at the department, alongside Alonzo Crawford, author of the critically acclaimed 1978 short documentary Crowded – Baltimore Prison Cell, who had begun lecturing at Howard a little earlier. An extensive profile about the department’s film program, published in Howard’s journal New Directions in 1983, speaks of a “small, struggling, innovative and potentially revolutionizing movement of Black filmmakers who deliberately have turned their backs on that sultry, flashy, dollar-bedecked siren—Hollywood—to inscribe on celluloid their own personal visions. Not surprisingly, many of these most forceful visions have to do with the liberation of Black people from oppression, whatever its particular form. As [Alonzo] Crawford has written, ‘It becomes obvious after analyzing the content of most films on the Black experience by Black filmmakers that they are all, in one way or another, films of resistance. Consciously or unconsciously, overtly or covertly, they have elements or images that resist forces in society that oppress Black people.’”

In the same article, Ford is quoted as saying, “Western cinema has successfully introduced the Western man in the manner he thinks of himself, maintained his culture in the manner that he thinks it should be maintained, amplified it in the manner that he wants it amplified and set the conditions of behavior, if you will, for imitation on the part of non-Western peoples to behave in a manner that satisfies Western man more so than anyone else. Film is enormously influential. It is one of the heavy artillery weapons in the battle for control of the human mind. That is why it is imperative that we use it and make it synchronic with our culture and needs.”

And since seventeen-year-old Arthur Jafa Fielder enrolled at Howard in 1978, soon proving to be the most talented and unruly student in the department, it may well be that he attended one or several of the classes or workshops that Skip Norman offered during these years. In another 1983 article on the department, “AJ” is described as having made “experimental films and videotapes, […] designed his own movie camera, which he’s trying to market, and considers film a ‘voodoo kind of thing’ to be used to combat negative images of Black people.” Jafa is further quoted with the following evidence of his pedagogical ambition: “I’m into this thing about tradition, passing certain things down, influencing people.” Enter Skip Norman?

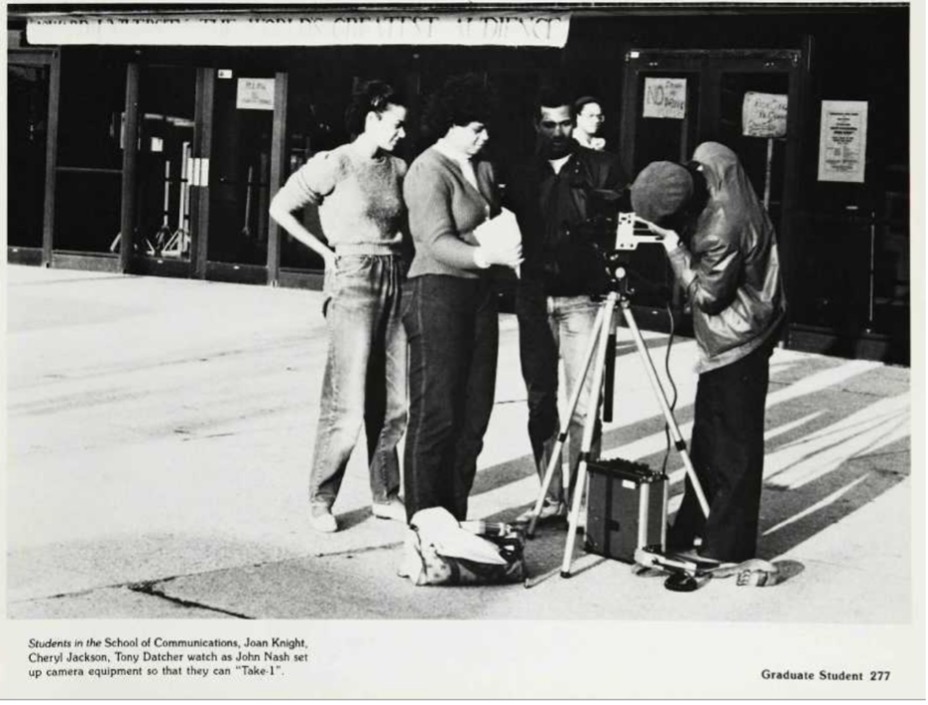

From Howard University, The Bison: 1983 (1983), Howard University Yearbooks, 153. https://dh.howard.edu/bison_yearbooks/153

References

Walter Dyson, Howard University—The Capstone of Negro Education. A History 1867–1940, Washington, 1941.

Harriet Jackson Scaraupa, “Filmmakers at Howard,” New Directions, vol. 10, nos. 3/4: 10th Year Anniversary Special Double Issue (1983), n. p.

November 11th, 2021 — Rosa Mercedes / 03 / Contexts