Black and White, Unite! Unite!

Ida and Wilbert Norman’s first son, Wilbert Reuben, was born on December 22, 1933 in Baltimore, Maryland. Later, he would go by “Skip” Norman. They were blacks. Racial separation was especially pronounced in Baltimore. While whites were moving to the suburbs, blacks stayed behind in the city. The run-down East Coast city is now known as “Bodymore Murderland”—in 2007 alone, 365 people were killed there.1

The family soon moved to neighboring Washington, D.C.—the “Chocolate City,” as the U.S. capital was also known, because more than half of its inhabitants were black. They lived on the city’s east side, while the whites lived on the west side. Although slavery had been abolished in 1865, Skip experienced “apartheid” growing up. “From the cradle to the grave,” African Americans lived separated from the rest of the population. They had to stay in designated schools, restaurants, public restrooms, buses, and trains, and anyone who violated this—and this could simply be an unwanted visit in a public park—had to reckon with (arbitrary) punishment. The official political slogan was “separate but equal” but in reality the whites ruled.2 Pogrom-like assaults, mistreatment, executions, and the lynching of “nxxxxs” by white mobs, organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, or white police officers, who often made ruthless use of their guns, all defined the life of an African American—and likewise Skip’s childhood and teenage years.

Skip’s father worked at the Pentagon for the Navy’s statistical division. His mother was a housewife and had many different jobs, including in an ammunition factory and as a school bus driver. Occasionally, she watched the neighborhood kids and also tried her hand at making her own ceramics. Because of his father’s government job, the family belonged to the middle class and had contact with whites—this was their first step out of the ghetto of apartheid. The education of Skip and his three brothers proceeded with corresponding strictness—they needed an “adjustment to reality.” In his “autobiographical notes” in his application to the Berlin Film School (dffb), he summarized: “I spent my childhood in Washington, D.C. My education went on in the usual way: Elementary school, middle school and high school, which I completed with an examination corresponding to the German Abitur.”3

Skip Norman studied German language and literature and travelled to Göttingen in 1961. There, he developed a love for theater in the German department’s drama class. His work in the student theater as an actor, assistant director, stagehand, sound engineer, and stage manager opened “the gates to the big theater” for him. In 1964–65, he acted in different plays in Göttingen at the Deutsches Theater and Junges Theater, including one with Bruno Ganz directed by Heinz Hilpert. In his 1966 film school application, he writes: “Film contains a means of expression that can hardly be realized in theater.”4

On September 17, 1966, Skip proudly sat—in a dark suit with a bow tie—in the Sender Freies Berlin (SFB) auditorium, where the official opening of the dffb took place. I came to the dffb only four weeks after it opened and met Skip in Peter Lilienthal’s directing class. In our first year, everyone shot a short film on black and white 16mm film. We worked together for the first time on Helke Sander’s film Subjektitüde (1966/67). I was cameraman and Skip was my assistant.

Helke Sander’s first film was shot on a cold December day in 1967. The shooting location: a bus stop at Innsbrucker Platz in Berlin-Schöneberg. We were filming an exchange of glances between two men and a woman. The plot is easily summarized. The two men indicate: I want you! She is confused but glances back—from the one to the other. The men size each other up. One of the men gets on the bus and drives away. We did multiple takes of his departure, his confused glance at the woman from inside the bus as it drives away, then the woman glancing at the man on the bus. Luckily, we had the permission of the public bus line. The bus pulled up and stopped five meters later. We could get off and shoot another take with the next bus. The main actress was an attractive Swede. We were all thinking in concepts, in glances.

In 1978, film critic Kraft Wetzel wrote about the film: “The four-minute Subjektitüde is a moderately funny cat and mouse game filmed exclusively in POV shots accompanied by internal monologues. With appraising glances and tactical movements, two men at a bus stop want to pick up a woman who drily comments on their preparations.”5

Skip’s first film is called Riffi (1966). Unfortunately, there is currently no available print of it. In the film, Skip did an unusual experiment that he developed with Holger Meins. Holger organized the entire film for Skip. I was camera assistant.

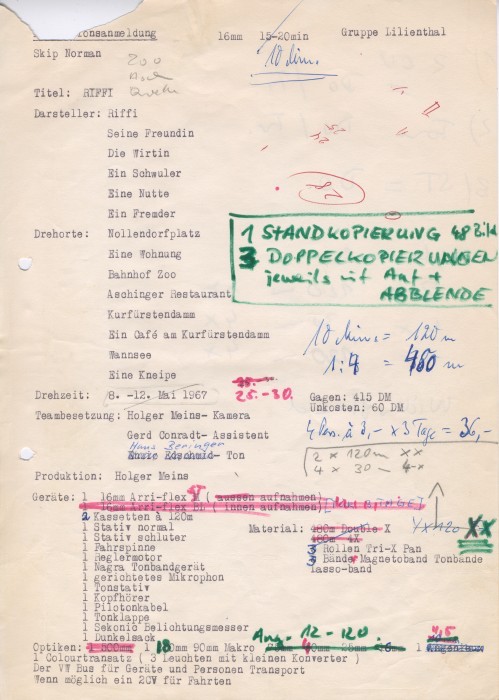

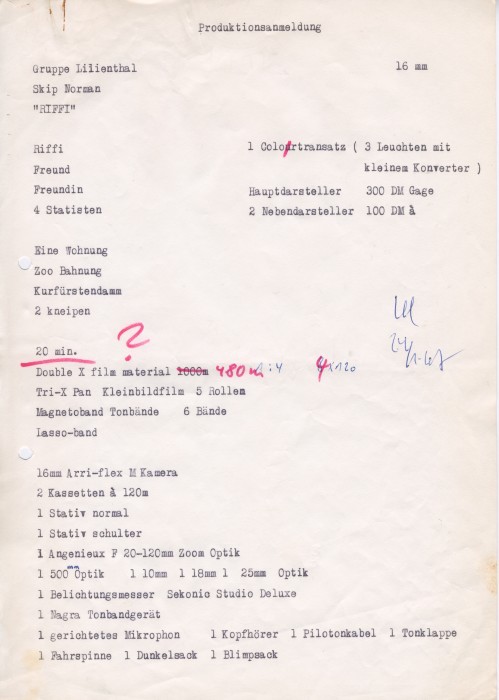

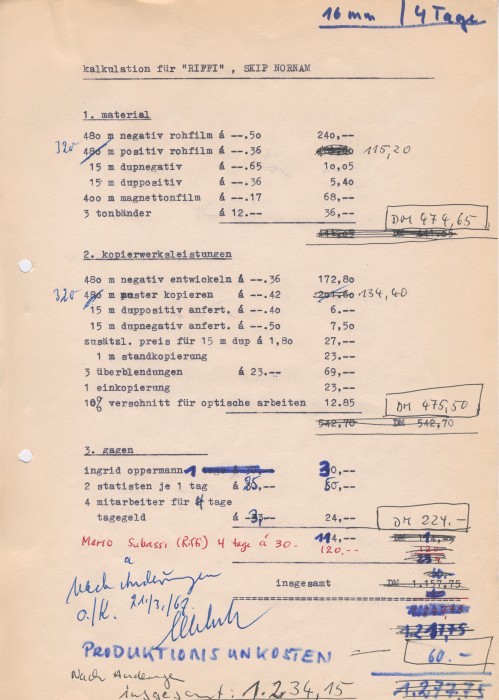

Production application for Riffi (1966)

Holger built dolly tracks in a 360-degree circle, surrounding a couple who communicated to the camera with their eyes alone. Sometimes she, sometimes he stood in the circle, sometimes they both stood outside of it, sometimes in it. Sometimes the camera looked over the shoulder, sometimes he or she was seen subjectively. I don’t remember there being any dialogue.

These shots were a major challenge for all of us. The dolly tracks had to be perfectly flat and even so that the camera would glide smoothly. Anyone in the room had to walk in a circle behind and with the camera. Some people have said that our camera teacher, Michael Ballhaus, was inspired by this “setting” for his famous 360-degree tracking shots that first caused a sensation in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Martha (1973).

We were thirty-five “trainees”6 excited about movie equipment and aesthetics. Our courage to experiment guided our work on our own films. That’s how we got to know each other.

The first large-scale political protests took place in the city in December 1966—in connection to the American war in Vietnam. Our films became more political. Some of us got involved in the growing extra-parliamentary opposition. There was especially criticism of newspapers owned by the Springer group, which influenced and determined public opinion in West Berlin.

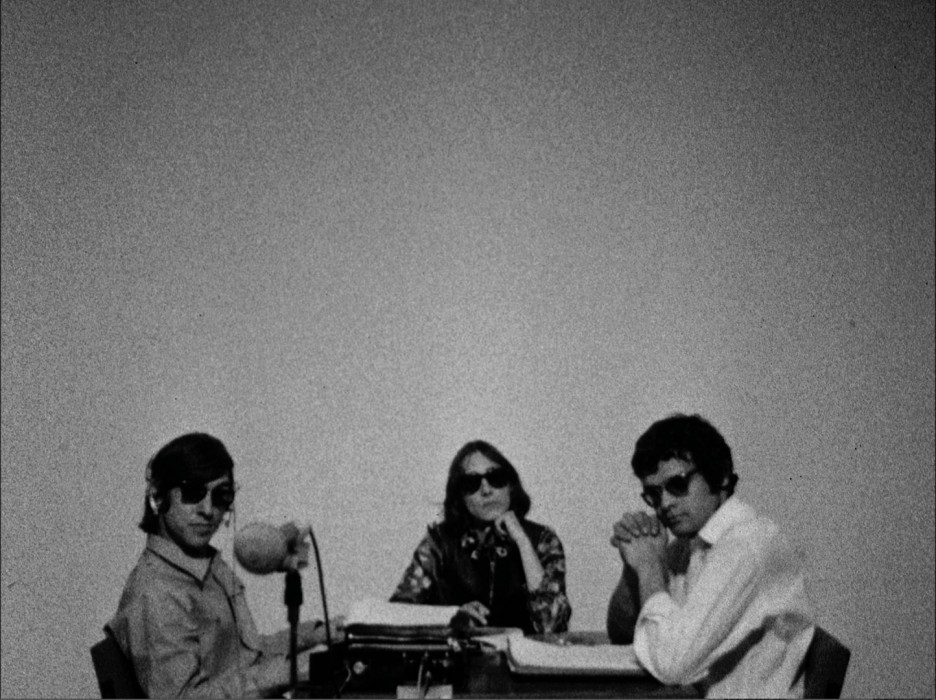

January 16, 1967 was warmer than usual for the season. No snow. In the Palais am Funkturm, the press ball was celebrating politics, business, and culture under the motto “Moderation–Consideration.” A dffb film crew had a press accreditation. In Helke Sander’s film Brecht die Macht der Manipulateure (Break the Power of the Manipulators, 1967–68), we see a short sequence where a young woman in a taffeta dress with a flared skirt goes behind the table where the evening’s most prominent guest, Axel Cäsar Springer, is seated. She pulls a banner out of the pocket of Ulrich Knaudt, who was recording sound: “Make politics with money—make money with politics.” Skip Norman, operating camera, managed to keep the action in the shot. The crew was very quickly arrested by police dressed in civilian clothing and taken out of the room. In another scene in the film, three of the filmmakers (Ulrich Knaudt, Helke Sander, and Harun Farocki) sit around a table alternately reading statements and thoughts aloud. Knaudt says: “Before the director takes a gun in his hand, he must himself stage the action that will prepare the overthrowing of society.” Sander expresses her revolutionary concerns more didactically: “I’m interested in how Springer can be shown in a documentary. Not in the role he’s happy to play and in which he is always reproduced, but in his function as a ruler. […] Springer must be put in a situation where he must choose between role and function. We have to produce this situation and we have to determine the tactics.”

Frame scans from Brecht die Macht der Manipulateure (1967-68). (1) Ulrich Knaudt, Helke Sander, and Harun Farocki. The microphone is directed towards the camera/spectator. (2) Under difficult conditions, Skip Norman films the unveiling of the banner at the Press Ball. (3) Skip Norman, Helke Sander, and Harun Farocki

Later, standing in front of a white wall, dressed in the “costumes of the bourgeoisie”—the men in smoking jackets, the women in evening gowns—the film crew summarizes its heroic act in unison: “Then we sat in jail for five hours and showed the proof: the relationship between role and function will only eliminated through revolution.”

These were words that soon appeared frequently in dffb films and quickly led to problems at and around the school: weapons, revolution, tactics—the overthrowing of society.

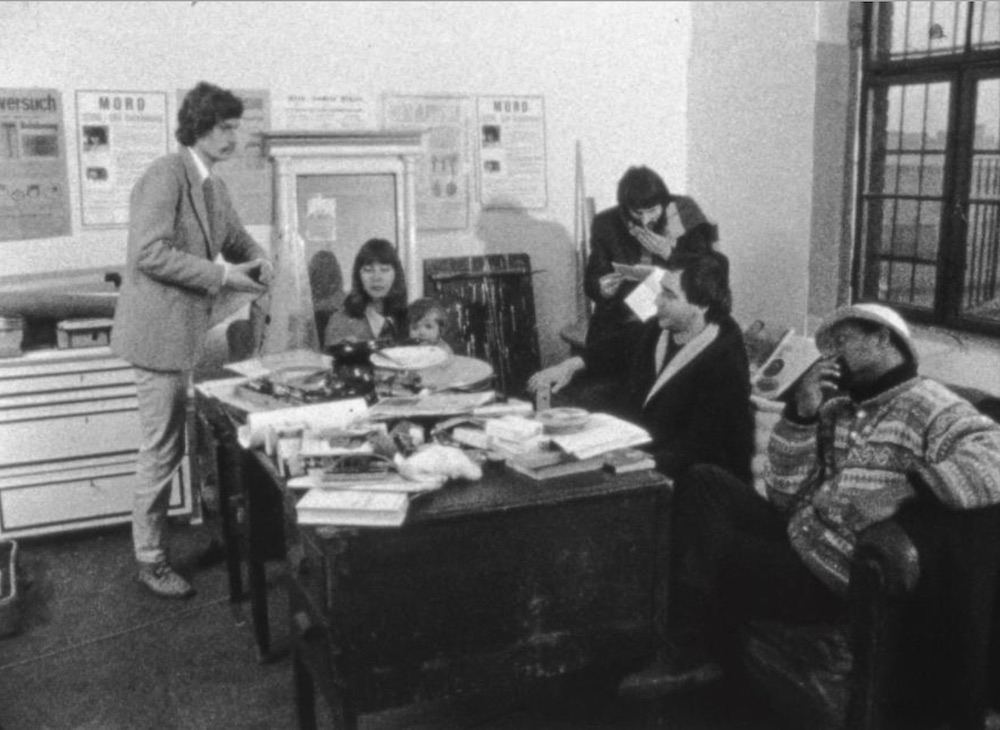

Gerd Conradt, with Lena und Alfa Conradt, Holger Meins, Günter Peter Strascheck and Skip Norman in Situationen (Situations, 1967)

A scene in Johannes Beringer’s film Situationen (Situations, 1967) was shot in my Kreuzberg loft. Three men (Skip Norman, Günter Peter Straschek, Holger Meins) sit around a table. A man (Gerd Conradt) stands across from them and a woman (Lena Conradt) is clearing the table at the other end with a baby (Alfa Conradt) in her arms. The baby is crying. The men discuss revolutionary film. Skip is silent. A document showing our “reality,” especially our relationship to women.

I worked on two more first-year films with Skip as camera assistant: Holger Meins’ Oskar Langenfeld: 12 Mal (Oskar Langenfeld: 12 Times, 1966) and Enzio Edschmid’s Der Tod von Sokrates (The Death of Socrates, 1967). We shot inside and outside and it was often cold. We would set up small lights inside. We had to be sparing with the film stock and often shot in a 1:4 ratio. For every film, we needed a production application: shooting days, equipment, personnel, actors, film stock, money—everything was scarce. We shot on negative film stock and usually started the take with the slate and an announcement for the sound—for documentary films as well. We needed the sync point for editing and the indication of which shot should or should not be printed. “P” (print) and “NP” (not print) stood in the camera report for the lab, which the assistant had to fill out carefully.

On the film Santa Lucia (1967), Skip was camera assistant for Holger Meins. Skip would often come visit me in the editing room at night to see how my editing was going. We spoke at length about montage and a film’s rhythm. He was excited about the early Russian and surrealist films. We were especially fascinated by Luis Buñuel’s Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1929). Peter Lilienthal showed us films by Jean Vigo. They gave us courage to believe in our own film language.

Set photos from Santa Lucia (1967). (1) Enzio Edschmid, Gerd Conradt, Holger Meins, Skip Norman. (2) Holger Meins. (3) Gerd Conradt

At the end of our third year, there was a big conflict between the board and us “trainees.” The dffb was not a publicly funded university. It was a privately-run academy. It was supposed to do business like a company—that’s why we were not really students but “trainees.”

Our performances were reviewed and only the ones whose films passed the test could continue studying. We were not told this beforehand. We demanded to know the criteria with which this review was being conducted. The films of six “trainees” did not pass this performance review. The board was not prepared to discuss their decision with us and we assumed that those who “flunked” were those who had excelled politically. There were a lot of protests, especially at the Berlinale, which still took place in summer at the time. The board ultimately gave in—everyone was allowed to continue studying, no one had to leave the academy. An academic council was even established so that in the future the board, lecturers, and “trainees” could decide together over the dffb’s fate—a truly revolutionary act of democratization.

The Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, and his wife Farah visited Berlin on June 2, 1967. Their visit to the city was accompanied by demonstrations during which a student, Benno Ohnesorg, was shot by the police. Thomas Giefer, a second-year “trainee,” captured many of the events with his 16mm Bolex. Together with Rüdiger Minow, who was also in Peter Lilienthal’s directing class, he assembled the film Berlin—2. Juni ’67 (Berlin—June 2, ’67, 1967). The cameraman was Skip Norman. The film was awarded a Silver Dove at the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animation Film. We were impressed—and so was the board. The artistic director, Erwin Leiser, congratulated the filmmakers on this meaningful honor.

Our films became more radical—not only ideologically, but especially in their film language. We came up with new films and were in the privileged position of being able to shoot them right away. Andy Warhol and Pop Art, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jimmy Hendrix, the Doors—and drugs—“expanded” our consciousness.

In February 1968, we received our first roll of color film: reversal stock. There was no negative. Like with Polaroids, what was shot was already a positive. I shot Farbtest—Die rote Fahne (Color Test—The Red Flag, 1968). Skip was camera assistant and our lecturer, Völsen, operated the camera.

Skip’s second film, Blues People (1968), shot in early 1968, was a huge success. For the nude scenes, Skip and his actress Li Antes collaborated with the Mexican cameraman Carlos Bustamante, who was in his second year. In order to concentrate on the intimate scenes, they met privately on the weekend.

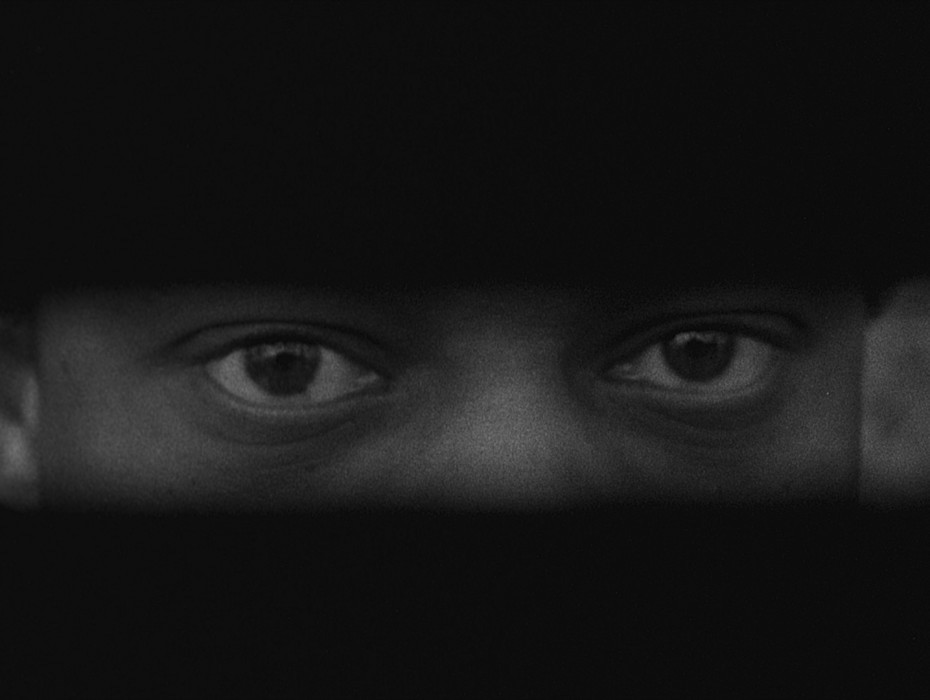

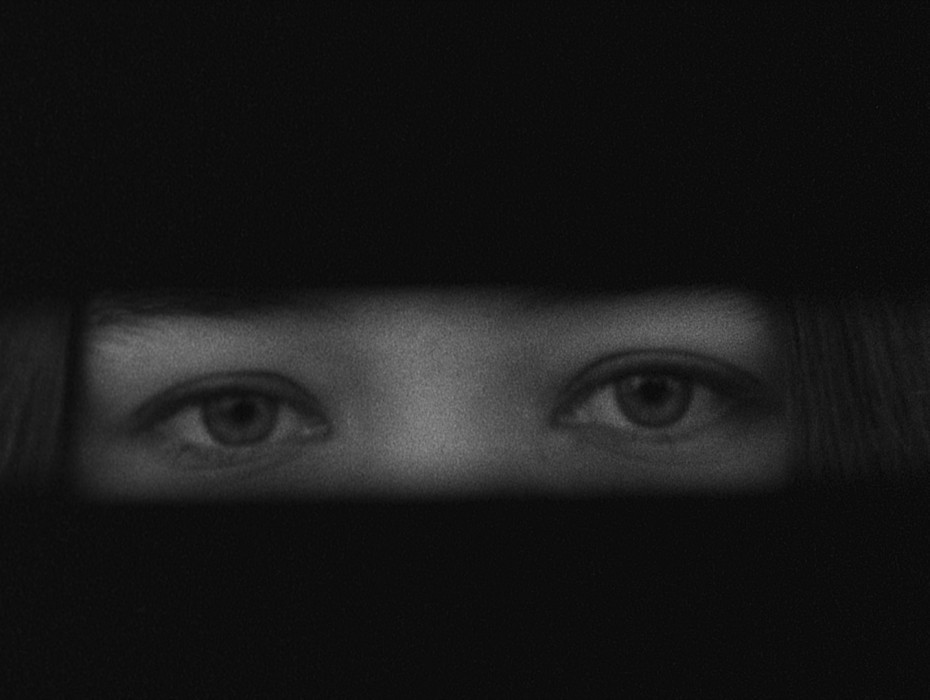

Frame scans from Blues People (1969). (1) Director and actor Skip Norman looks through a slit into the camera. (2) Li Antes and Skip Norman are sleeping together. (3) Li Antes looks through a slit into the camera.

After Blues People premiered at the 15th West German Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, Hans Günter Pflaum wrote: “For me, the strongest film not only in the German program, but in the entire festival, was Skip Norman’s Blues People. The American dffb student (born in 1933) has done something that even major filmmakers like Murnau or Eisenstein rarely managed. Norman places contradictions side by side, not to cancel them out or to reconcile them, but to make an age-old injustice and a major dichotomy tactile and concretely understandable. The film is accompanied by the sound and lyrics of the blues, which lend it a sad and melancholy aura. Norman brings an operation to its conclusion in his film: he frees the blues from their inner aggression. To do so, the director employs an advanced symbol: a black man together with a white woman. There is nothing pornographic here. Norman couldn’t have chosen any other images. They are absolutely legitimate. Only with this kind of radicality can it be made clear that even the union of two people cannot overcome socially and politically imposed racial divisions. Blues People is forced to become an agitation film. But its call to action is expressed with the greatest possible lyrical strength and sensibility.”

The film was bought by West German public television, but Bavarian public broadcasting refused to show it, claiming that the shots in the film showing a buttocks and genitals (breasts, vagina, penis) of a white woman and a black man constituted pornography.

Film scholar Dr. Gerd Albrecht, who taught film analysis at the dffb and who knew most of the students and their films, wrote the following in an exemplary report: “The film has a running time of approximately 17 minutes and contains 53 shots. The shots are therefore, on average, rather long. Consequently, what the images show can, at least in part, be inspected for a very long time. It must be noted here that shots of long duration—ceteris paribus!—provide great incentives for identification. In the film, six objects of study are visible that do not completely meet but that are connected in different ways. […] The intimate scenes take up about a fourth of the film. […] The creative passion visible in the film’s structure and content thus clearly points to connections between sexuality, aggression, and prejudice—a theme already audible in the title, Blues People. The extent to which the creation can be described as successful is not under debate here as that is irrelevant to the accusation of pornography. […] Finally, it can be stated that based on an analysis taking into consideration the relevant jurisprudence, the question of whether Blues People constitutes pornography can be answered with NO.”7

The mood in relation to the question of racism in Germany can be illustrated by some remarks in the newspaper Handelsblatt from March 1969: “I can for this reason not accept a film praised in Oberhausen like Blues People because I cannot understand how the detailed representation of a sexual act is necessary in order to draw attention to the nxxxx problem in America.”8

As I was researching this article, Helke Sander told me the following story: she was sitting with Skip and Enzio in a café across from the dffb on Theodor-Heuss-Platz. There was war in the Middle East. The Arab countries were fighting against Israel in the Six Days War. Helke to Enzio: “From now on, there has to be at least one woman, one Jew, and one nxxxx in every new class.” Skip protested: “The word ‘nxxxx’ is discriminatory. Now we say ‘black.’”

Bobby Seale. Frame scan from Strange Fruit (1969)

Skip’s thesis film is called Strange Fruit (1969). The appearance of Bobby Seale—one of the founders of the Black Panther Party (BPP)—at a convention in Copenhagen stands at its center. The Black Panthers were African Americans who did not only propagate “Black is Beautiful,” but demanded the right to use force and weapons—and who called for guerrilla warfare. They would appear in public dressed in black, wearing berets, leather jackets, gloves, military boots, and with machine guns slung over their shoulders.

Strange Fruit is the name of an old blues song about “strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees,” meaning lynched black people. Skip edited excerpts from Bobby Seale’s speech and photos of hanging black people with footage of U.S. military buildings in Berlin. These were the U.S. military barracks and headquarters on Clayallee in the neighborhood of Dahlem. The footage is accompanied by the most famous recording of Strange Fruit, Billie Holiday’s. Typical of the political films of the time, he used intertitles as a dramatic element. The titles summarize, emphasize, and play with words—they are often slogans. “Genuine self-determination for blacks and other oppressed ethnic groups cannot be achieved in the frame-work of capitalism, imperialism, and racism.”

Strange Fruit was shown on West German TV in August 1971 together with a film Skip shot in his hometown after graduation, Washington D.C. November 1970 (1970). The film is a valuable document. According to the production application, it cost 9,681.28 DM—calculated down to the Pfennig.

Frame scan from Cultural Nationalism (1968-69)

Skip shot his film Cultural Nationalism (1969) according to the “one day, one shot” principle. We see a white surface, the horizon is a black line under a gray sky. We hear Bobby Seale’s voice. He is talking about the repression of African Americans in the U.S. He quotes French psychiatrist, political philosopher, and de-colonization pioneer Frantz Fanon (1925–1961). After about six minutes, there is a barely noticeable cut. A small, dark dot begins to approach the camera—at the end we see the uneasy, laughing face of a young black kid. A great film that Skip shot as a kind of stylistic exercise on the frozen, glittering snow-covered Wannsee.

November 27, 1968 was a dark day in the history of the dffb: Seventeen “trainees” were banned from the building and expelled. I was one of them. I lost contact with the students who remained—including with Skip.

In 2001, I shot the feature-length documentary Starbuck—Holger Meins. Skip appears twice in the film: silent in the scene in my loft where we are discussing revolutionary film and in a scene from Hartmut Bitomsky’s Johnson & Co. und der Feldzug gegen die Armut (Johnson & Co. and the Campaign Against Poverty, 1968), in which, in the role of a “worker,” he talks about exploitation.

Skip saw the film and, in the fall of 2002, invited me to Northern Cyprus where he was teaching as a professor of ethnographic photography on the faculty of Communication and Media Studies at Eastern Mediterranean University (EMU).

This was convenient because I had always wanted to get to know the northern part of Cyprus, which had been annexed by Turkey in 1974. Lawrence Durrell’s book Bitter Lemons (1957) had made me curious about the legendary island.

Skip had returned to the U.S. in 1975. He couldn’t survive as a film artist in Germany. In the U.S., he shot films commissioned by colleges and public institutions and worked as a photographer. At the same time, he began a degree in anthropology at Ohio State University in Columbus and completed his doctorate in 1980.

From this point on, he combined his passion for images—as a photographer and cameraman—with his interest in the lives of people, with anthropology.

He greeted me on the runway with, “Man Gerd, I didn’t think you’d actually come visit me.” It was as if thirty years hadn’t gone by between this meeting and our last one. He rocked me gently through the mild evening on the Mediterranean island in his old, white Mercedes. I wanted to go out, but he said we were in a Muslim country, not in Berlin where bars stay open until the early morning. I was welcomed with herbal tea. The next day, I visited him at the university and he invited me to eat in the cafeteria. In the evening, we talked about the past and I learned a lot about his film work that I hadn’t known.

Skip was probably one of the hardest working “trainees” at the dffb—he was involved in the production of a total of 27 dffb films. After graduating, he worked as cameraman on a number of important films: Malte Ludin’s Kennen Sie Fernsehen? (Do you know TV?, 1973), Lothar Lambert and Wolfram Zobus’ 1 Berlin–Harlem (1974), Allan Kaprow’s Warm-Ups (1975), and Jonatan Briel’s Glutmensch (Fervent Person, 1975), where Skip Norman’s hand in the image can be clearly felt. The latter film is a portrait of the poet Friedrich Hebbel. Its poetic visual language and experimental editing turned it into a piece of art itself.

In 1974 and 1975, Skip held a teaching position in the dffb’s camera department. As he was going begin to study anthropology in the U.S., he asked the director of the dffb, Dr. Heinz Rathsack, for a letter of recommendation. Rathsack wrote:

“The different productions that you produced under your own responsibility as author and director document that you command all of the skills and necessary talent for organization that are required to direct films even in the most difficult conditions. During your time teaching at our academy, you have proven your talent for educating and strove to communicate both your technical knowledge and your artistic experiences with equal intensity. As you are now departing, I feel a sincere need to say that it has been a pleasure to work with you over the past nine years and because of the candor and sincerity you have always shown me, I feel we will remain on cordial terms.”9

Helke Sander told me another story about how she and Skip appeared on the cover of Frauen und Film magazine along with Alexandra Kollontai (1872–1957), the Russian women’s rights activist and “People’s Commissioner for Welfare.”10 On February 15, 1975, Helke was filming a protest action against German abortion laws at the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. Demonstrators poured washable red paint over the church steps to symbolize the blood flowing from illegal abortions. When the police began to interfere in Helke’s journalistic work and wanted to arrest her and take away her equipment, she saw Skip in the crowd—with his camera in his hands. She called out: “Skip, take a photo!” Skip had just come to Berlin by train and happened to walk by. Since he seemed to know the reporter Helke Sander and was apparently taking photos for her, he was arrested too.

April 22, 2002 was an important day for Northern Cyprians. I observed Skip at work with my DV camera. A new mosque, the biggest one in Northern Cyprus, was being inaugurated with much fanfare. Skip took photos and greeted political and religious representatives—he was well-known and happy to be seen as an anthropology professor at EMU. My footage shows Skip at work: he posed for my camera, knowing I was watching him—a wonderful document that hasn’t been released yet.

The evening before my departure, we drove to the village where Lawrence Durrell had lived. In Bitter Lemons, he describes the multifaceted coexistence of Turks and Greeks on Cyprus in the 1950s.

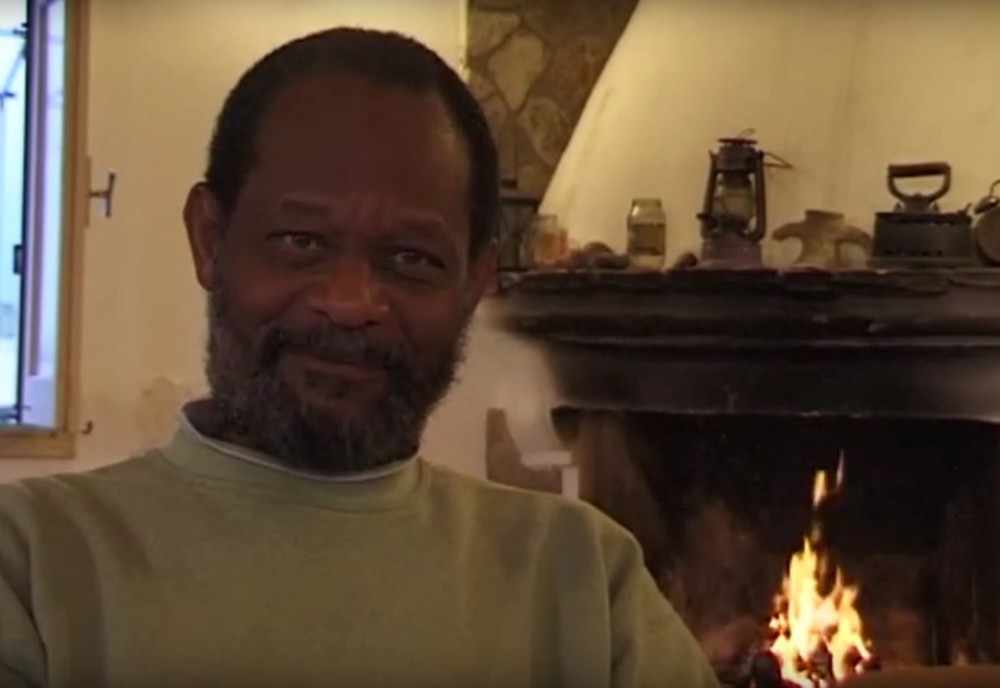

During my stay, I kept thinking of doing an interview with Skip about his time at the dffb. On this final evening, we found a small roadside restaurant where we could do more than eat good fish. The owner allowed us to shoot the interview in his empty dining room as well as to light a fire in the fireplace—the fire in the image provides a warm atmosphere. Something is burning, something new is arising.

Skip Norman in dialogue with Gerd Conradt on Cyprus, 2002

“When we had the group discussions and Lilienthal was trying to get us to think about what we wanted to do, whether or not we wanted to direct or do the camera […], I think one of the things that I remember is that Holger [Meins] basically suggested, we could do anything and everything, you know? We don’t have to be directors or camera people, we can just be filmmakers.’”11 That impressed him, Skips says in the interview. As Skip came to Berlin to study and still didn’t have a room, Holger Meins was the one who offered him a loft bed “right under the roof” at his place. “We were all really focused on film work. We knew very little about each other privately. We were young people who wanted to find something in ourselves that we wanted to express on film. We showed each other our talents,” says Skip.12 “There were some people in the academy who were far better trained in expressing ideologies than others. […] In the second year, these ideologies began to take hold in the academy. […] At some point it became impossible to step back from the politics of the scene, if you wanted to take part in the scene. The only way you could not be a part of the scene is if you stepped back from it. And some people did step back from, they just decided not to be involved politically and just to do their own thing. […] I found it right to be against the Vietnam War. […] By the second year, almost all the films had become political. Films became slogans more than artworks. […] You were no longer allowed just to talk but had to show you were right up on the cusp of things.”13

On March 13, 2015, I posted the interview on Youtube.14 Me and a few other alumni tend to the history of the dffb—2016 was its 50th anniversary. I saw the publication of the interview as a contribution to this work. In secret, I hoped Skip would hear about it and get in touch. One week later, I received the news by e-mail that Skip had died just a few days later on March 18, 2015 at his parents’ home in Washington D.C.

Willy Brandt, who had established the dffb, had high esteem for Martin Luther King. “His noble pathos and his moral strength appealed across the language barrier,” he emphasized as foreign minister when King was murdered in April 1968 and the Black Panthers declared the principle of non-violence as failed and houses in hundreds of cities across the U.S. went up in flames over the following days.15 King’s dream that the “sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners” could sit at the same table, had failed.16

The poet Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) is buried in Baltimore, the city where Skip Norman was born. Skip liked his poem “The Raven.” In 1968, we went together to the legendary Frank Zappa concert with his band The Mothers of Invention at the Sportspalast in Berlin. Like Skip, Zappa was also born in Baltimore.

I’ve just discovered the story of the postal worker William Lewis Moore from Baltimore. Moore was a civil rights activist: he protested against racism in marches across the U.S., he delivered letters, and, on his final protest march, he carried two signs: “END SEGREGATION IN AMERICA” and “EQUAL RIGHTS FOR ALL MEN.” On April 23, 1963, a motorcyclist found Moore lying dead on the side of a road. He had been shot in the head nearby with three bullets from a 22. Caliber pistol. The poet Wolf Biermann deals with Moore’s story in the “Ballade vom Briefträger William L. Moore aus Baltimore.” One of Biermann’s lines is: “Black And White, Unite! Unite!”

Originally written for the website dffb-archiv.de in German. Translated by Ted Fendt.

Gerd Conradt studied film at dffb between 1966 and December 1968 when he and seventeen other students were expelled from the school. In addition to his own dffb films like Santa Lucia (1967) or Farbtest: Die Rote Fahne (1968), he was also the cinematographer for Harun Farocki’s post-dffb film Inextinguishable Fire (1969). Since the 1970s, Conradt has pioneered working with video, directed many films and videos, and taught at various schools. In several productions including in the movie Starbuck Holger Meins (2001), he has revisited the dffb period and his friendship with Holger Meins.

Footnotes

1 Frances Stead Sellers, “Life and Death in Bulletmore Murderland,” The Guardian, January 17, 2008. URL: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/jan/17/bulletmoremurderland (visited on 07.01.2015). 1

2 “Separate but equal” served as the legal principle that defined the racially-divided handling of the African American minority in the South between 1896 and 1954 and the relationship between the two most important demographic groups. 2

3 Source: Deutsche Kinemathek, dffb Archive. Folder number: N12697_DFFB NORMAN, Skip. 3

4 Ibid. 4

5 Günter Pflaum, “XV. Westdeutsche Kurzfilmetage in Oberhausen, 23.- bis 29. März,” Jugend, Film, Fernsehen, 2/69, p. 98. From the Blues People production card. Source: Deutsche Kinemathek, dffb Archive. Folder number: F35314_N12697_01 to 07. 5

6 Trans. note: German has two words for student: Studenten and Studierende. Conradt calls dffb students Studierende (“trainee”) because they were in a private film academy, receiving an Ausbildung, or professional training, rather than a Bildung, or general education, such as public university would offer. I have therefore translated Studierende as “trainee” throughout and kept the quotation marks Conradt employs around the word. 6

7 Gerd Albrecht, “Analyse des Films ‘Blues People’ unter dem Aspekt ‘Handelt es sich um Pornographie?’” pp. 1-7. From the Blues People production file. Source: Deutsche Kinemathek, dffb Archive. Folder number: F35314_N12697_DFFB. 7

8 Excerpted from a review of Blues People in Handelsblatt, March 25, 1969. From the Blues People production file. Source: Deutsche Kinemathek, dffb Archive. Folder number: F35314_N12697. 8

9 Deutsche Kinemathek, dffb Archive. Folder number: N12697_DFFB NORMAN, Skip. 9

10 Cover illustration, Frauen und Film, 1975, Heft 5. URL: http://www.frauenundfilm.de/?site=hefte&rid=5 (visited on 08.18.2015). 10

11 Skip Norman in conversation with Gerd Conradt, November 22, 2002, Northern Cyprus. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFG0Dlm-Ln8 (visited on 07.21.2015). 11

12 Ibid. 12

13 Ibid. 13

14 Ibid. 14

15 Die Zeit, May 13, 2015, p. 17. 15

16 “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” Excerpt from: Martin Luther King, “I Have a Dream,” closing speech at the Lincoln Memorial on the occasion of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963, Washington D.C. 16

[Suggested citation: Gerd Conradt, “Black and White, Unite, Unite!” Rosa Mercedes 03/B (April 2021), www.harun-farocki-institut.org/en/2021/04/30/black-and-white-unite-unite/]

April 30th, 2021 — Rosa Mercedes / 03 / B