The server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout (Journal of Visual Culture & HaFI, 39)

This is the thirty-ninth instalment of a collaborative effort by the Journal of Visual Culture and the Harun Farocki Institut, initiated by the COVID-19 crisis. The call sent to JVC’s editorial board, and a wide selection of previous contributors and members of its extended communities, described the task as follows: “There is a lot of spontaneous, ad hoc opinion-making and premature commentary around, as to be expected. However, the ethics and politics of artistic and theoretical practice to be pursued in this situation should oblige us to stay cautious and to intervene with care in the discussion. As one of JVC’s editors, Brooke Belisle, explains: ‘We are not looking for sensationalism, but rather, moments of reflection that: make connections between what’s happening now and the larger intellectual contexts that our readership shares; offer small ways to be reflective and to draw on tools we have and things we know instead of just feeling numb and overwhelmed; help serve as intellectual community for one another while we are isolated; support the work of being thoughtful and trying to find/make meaning…which is always a collective endeavour, even if we are forced to be apart.'” TH

The server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout

By Arts Catalyst with Gary Zhexi Zhang and Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak (Pirate Care)

Prelude

By Laura Clarke & Anna Santomauro, Arts Catalyst

In 1999, Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star published Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences, exploring ‘how classification systems can shape both worldviews and social interactions.’[1] In defining infrastructure, the question of visibility is raised: ‘The normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks: the server is down, the bridge washes out, there is a power blackout.’[2]

At the same time, companies and organisations across the world had been preparing for the ‘Year 2000 Problem’ – an anticipated mass infrastructural problem whereby the original coding of complex computer systems would be unable to correctly interpret new calendar data from 2000 onwards, potentially causing a major glitch in communications, banking systems, power plants and transportation. Would the infrastructure support the future?

In late 2019 amongst an accumulation of crises, another glitch in the system emerges, along with rampant speculation, conspiracy theories and misinformation. A different kind of virus began spreading across the planet, with its effect on humans, non-humans and our systems of organisation and governance revealing the already broken infrastructures which enabled its unexpectedly potent agency.

On the 23rd of March 2020 the UK woke up to a visibly broken infrastructure, with fragments of it scattered everywhere. Already shaken by the Brexit vote, it was the first time since the financial crisis of 2008, and even then, the financial crash was so abstract and immaterial that the cracks that it produced in public infrastructures remained opaque, at least initially. Symptoms of infrastructural collapse had been appearing in public health, education and environmental policies among others though, in the form of the restructuring of public bodies, budget cuts and externalisation of public services.

But while austerity was seeking to shape the tectonic of society in an almost inevitable way, a proliferation of social movements, protests, demands – from Occupy Wall Street to BLM, from Me Too to movements for housing rights and migrants’ rights – have emerged. If we have not yet seen them fully cement into law, policy and party politics, we know that their echoes will continue reverberating in the system’s cracks, each time becoming louder and more visible.

—

Propositions

By Laura Clarke & Anna Santomauro, Arts Catalyst

During the lockdown, many of us have found themselves sitting – on our own – at a kitchen table, seeking to look into the future of the different overlapping structures that sustain our fragmented society. From our side, we have invited artists and practitioners who have an ongoing commitment to the redefinition of infrastructures of governance, decision making and care to develop a series of propositions for a visible infrastructure. While imagining sitting together at that same kitchen table – an eloquent metaphor of a temporary conflation of life – our first guests Gary Zhexi Zhang and Pirate Care have formulated the first propositions. This process will continue on Arts Catalyst’s website over the next 12 months.

At the kitchen table, we asked:

Who and what is within or outside of infrastructures? Who and what is reinforced or dismantled? Who shapes it and whom does it shape?

How can we rebuild infrastructures through cultural practices? If infrastructures are built to uphold a set of values or societal/economic/political/environmental norms, how can we shift the values of profit, accumulation and growth to be read through empathy, hospitality and care?

What would exponential growth along the vector of empathy look like? What would an abundance of comfort feel like? What if the organising principle of cultural infrastructure was the kitchen table?

Sakiya: Art, Science and Agriculture is an artist-run institution and permaculture farm in Ein Qiniya, Palestine. Founded by Sahar Qawasmi and Nida Sinnokrot, Sakiya hosts research, pedagogy and exhibitions that explore the politics and culture of land, infrastructure and the commons. Image courtesy of Gary Zhexi Zhang.

Proposition #1: The place of culture for a radical societal vision

By Gary Zhexi Zhang

Over the past few months, as COVID-19 brought global infrastructure to its knees, the way in which communities and governments responded has also shown how much of the impossible could, in fact, be implemented quite quickly. From remote work to mutual aid funds, from requisitioned housing for the homeless to a 25% drop in daily carbon emissions, it has been at turns inspiring and frightening to see how much can change on a whim. A catastrophe is an ‘overturning’, after all.

There is an opportunity to reflect on the value of culture: not only its intangible, intrinsic virtues, but its strategic efficacies in shaping the form and content of society. The pandemic transformations that took place seemingly overnight (no, the economy was always fictional; yes, we can decelerate if we want to) should give us cause to heighten our ambitions, as well as our demands, over what our collective future looks like. In this era of intense social and political uncertainty, perhaps it’s time that artists and cultural researchers work towards institution-building and policymaking, in order to stake a claim on an experimental public culture and a radical societal vision, committed to values beyond engagement metrics and private patronage.

Primer is a platform for artistic and organizational development located in the headquarters of Aquaporin, a water technology company in Denmark. Its stated objective is ‘renewing relations between artistic, scientific, technological and business practices’ by developing ‘novel organisational forms’. Image courtesy of Primer.

Artistic modalities of speculation and consciousness-raising are only as generative as their effects, or else they end up as more content for the churn in a futures-oriented economy whose currency is dopamine and affect. What would it take to shift the work of artists from the spaces of consumption to an intervention in the context of production, long term thinking and decision-making? For instance, what if there were not only economists and private lobbyists but also artists and cultural agents in the government committee, on decisions that affect not only GDP but the whole of society, such as climate policy, innovation, and indeed, cultural strategy? What institutions, pedagogical modes and strategic plays would be necessary for artists to take on the agency and responsibility of infrastructural-scale practice, to shape the real beyond the preserves of riskless speculation?

Diagram by Bahar Noorizadeh, “Art and Law”; from BLOCC, a system of learning that tackles the relationship between contemporary art and gentrification through an initial curriculum that aligns local struggles with planetary-scale infrastructural analysis. Image courtesy of the artist.

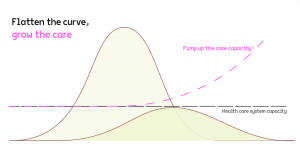

Proposition #2: Flatten the curve, grow the care

By Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak (Pirate Care)

In late 2019, we organized a collective writing retreat hosted by the cultural centre Drugo More in Rijeka (HR), to create a Pirate Care Syllabus – a free digital tool for sharing tacit knowledges and activating political pedagogies from disobedient practices of social reproduction and solidarity that are increasingly becoming criminalized. As the syllabus and its dedicated library catalog went online (https://syllabus.pirate.care) on March 8th 2020 for the opening of WHW’s exhibition “…of bread, wine, cars, security and peace” at Kunsthalle Wien, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic was already bursting in our part of the world.

So, we rolled over our work into a collective note-taking effort to document the unprecedented wave of organizing around mutual aid in response to the pandemic.

We titled the exercise “Flatten the curve, grow the care: What are we learning from Covid-19”, to problematize the famous image depicting a graph of the outbreak, with two curves representing better or worse rates of contagion and an undefined “healthcare capacity” as a straight line that the ideal pandemic curve should not breach.

Diagram by Pirate Care, “Flatten the curve, grow the care”. Image courtesy of Pirate Care.

From the perspective of learning with our extended pirate care network only a few months earlier, much in what has been termed the biggest crisis of care of the century seemed not so new. The straight line in the graph was actually depicting the flat-lining of the societal capacity of care under relentless austerity. The pre-existing capitalist care crisis, felt until recently by the most vulnerable and disposable populations, and always well visible through the lenses of class, race and gender, suddenly detonated as a generalized social fact.

What the research underpinning our process shows is that the straight line has never been the same line for everyone to begin with. It also shows that, crucially, this very line, representing the concept of a universally accessible public healthcare infrastructure as a common good, would not have been there if it wasn’t for those who in the past have organized around their own care needs, while simultaneously struggling for public welfare provisions shaped by their constituencies.

[1] https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/sorting-things-out

[2] https://highlights.sawyerh.com/highlights/Wi5FgG8ms2FtGzcJuvLA