Is the Jet Age Over? (Journal of Visual Culture & HaFI, 1)

This is the first instalment of a collaborative effort by the Journal of Visual Culture and the Harun Farocki Institut, initiated by the COVID-19 crisis. The call sent to JVC’s editorial board, and a wide selection of previous contributors and members of its extended communities, described the task as follows: “There is a lot of spontaneous, ad hoc opinion-making and premature commentary around, as to be expected. However, the ethics and politics of artistic and theoretical practice to be pursued in this situation should oblige us to stay cautious and to intervene with care in the discussion. As one of JVC’s editors, Brooke Belisle, explains: ‘We are not looking for sensationalism, but rather, moments of reflection that: make connections between what’s happening now and the larger intellectual contexts that our readership shares; offer small ways to be reflective and to draw on tools we have and things we know instead of just feeling numb and overwhelmed; help serve as intellectual community for one another while we are isolated; support the work of being thoughtful and trying to find/make meaning…which is always a collective endeavour, even if we are forced to be apart.'” TH

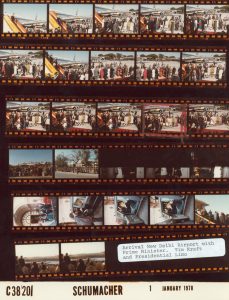

The U.S. National Archives

Is the Jet Age Over?

If anything could stand-in as a primary culprit in the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus that is circling the globe with seemingly unprecedented speed, it might be the jet plane. At the same time, cancelled flights and empty airports also stand as potent symbols of how life during the pandemic has been coming to a standstill almost as rapidly as the jet flies. But carrying symbolic weight is nothing new for jet planes. They have always seemed to function as heralds –proclaiming more than they could actually ever measurably deliver. In 1957, architect William Pereira, who with his partner, Charles Luckman, led the mid-century redesign of Los Angeles International Airport, explained, “At this very moment, history is classifying the Jet Air Age…we are realizing our future now almost as fast as we can visualize it.” The jet inaugurated not just the availability of a new speedy mode of transport but also gave rise to a new age, “the Jet Age.” Is the COVID-19 pandemic, complete with the possible moratorium on air travel, the end of the jet age?

The jet defined an age because it changed subjective experience, not because it went fast. As the historian Daniel Boorstin noted in his classic book, The Image (1962), “The newest and most popular means of passenger transportation to foreign parts is the most insulating known to man…I had not flown through space but through time.” Boorstin even complained that the non-experience of jet flight did not merely lead to in-flight boredom, which resulted in the airlines’ introduction of movies and bars aboard. It also led modern people to lose all sense of history, which he considered a function of people understanding how time was located across space. The jet, he complained, robbed passengers of the experience of the landscape. He concluded: “We look into a mirror instead of out a window, and we see only ourselves.” Boorstin predicted that the jet would lead to a hyper-individuated society of narcissists. Writing in the same year, cultural critic Marshall McLuhan noted, that “travel differs little from going to a movie or turning the pages of a magazine.” These prescient observers understood that the jet was about more than fast travel. They dug deeper than pointing to the jet as a key element of the globalization that seems to make the world smaller and thus, for example, facilitate the spread of epidemics more quickly. (We have heard this invoked endlessly to explain how the COVID-19 pandemic differs from the Spanish flu.) The jet, they could see, participated in a larger cultural shift from the late 1950s to the late 1960s — a jet age aesthetic — which glamourized fluid motion.

During the period, the experience of being in the jet was extended, in a variety of new cultural forms, to life on the ground. Jet age people learned to toggle between the material and immaterial worlds; navigating between such newly built spaces such as jet-age airports, Disneyland (which was one of the era’s most enduring creations and is a place built around transportation and people-moving – also closed during this current epidemic), as well as via contemporary media forms such as weekly picture magazines, which saw their heyday during the jet age. The jet age did not just make the world smaller because people (and viruses) could travel faster, it ushered in a culture that would conceive of the “networked society” in which we could imagine being connected without being physically present.

As people around the world prepare to “shelter in place,” we may not be happy that we are grounded and we are right to be extremely afraid of the costs of the current pandemic. At the same time, we are also ready to live and survive while staying in place. We will teach online for the duration. We visit and socialize with each other via Zoom and FaceTime. We stream a remarkable selection of fiction films, documentaries and series. We order essential provisions on-line. Daniel Boorstin was both right and wrong. He understood that the fluid motion of the jet would lead to a society that would invent its own fantasy of “surfing” the internet and literally go no place at all. But he could not have anticipated that we don’t just look in the mirror and see ourselves. We will have been able to go through this looking-glass in a time of crisis and create new forms of human community and connection. To be able to shelter in place from a deadly pandemic while eating freshly delivered provisions and seeing one’s geographically distant friends and family may not always be better than being physically together – until it saves your life.

Vanessa Schwartz is director of the Visual Studies Research Institute at the University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, and the author of Jet Age Aesthetic: The Glamour of Media in Motion (Yale UP, 2020)

March 30th, 2020 — Rosa Mercedes / 02